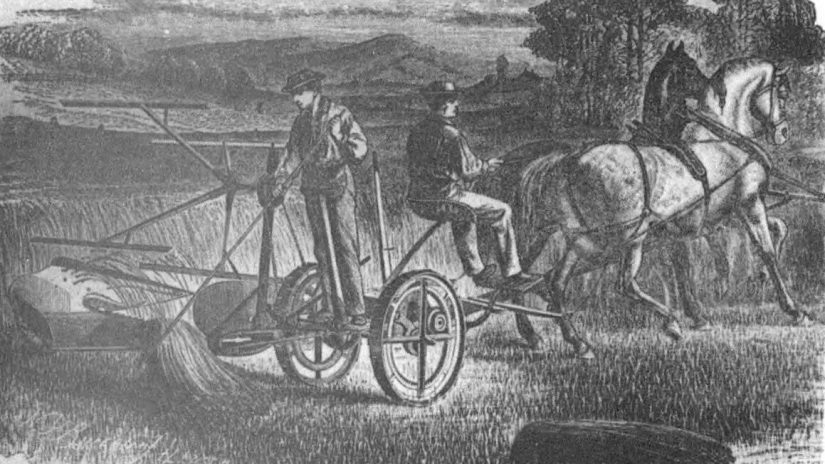

Benjamin Warder began building reapers at Spring field, Ohio in 1850. Prior to that time, Warder had established a sawmill, grist mill, and woolen mill. A factory designed to make small farm tools was even tually converted to a reaper building.

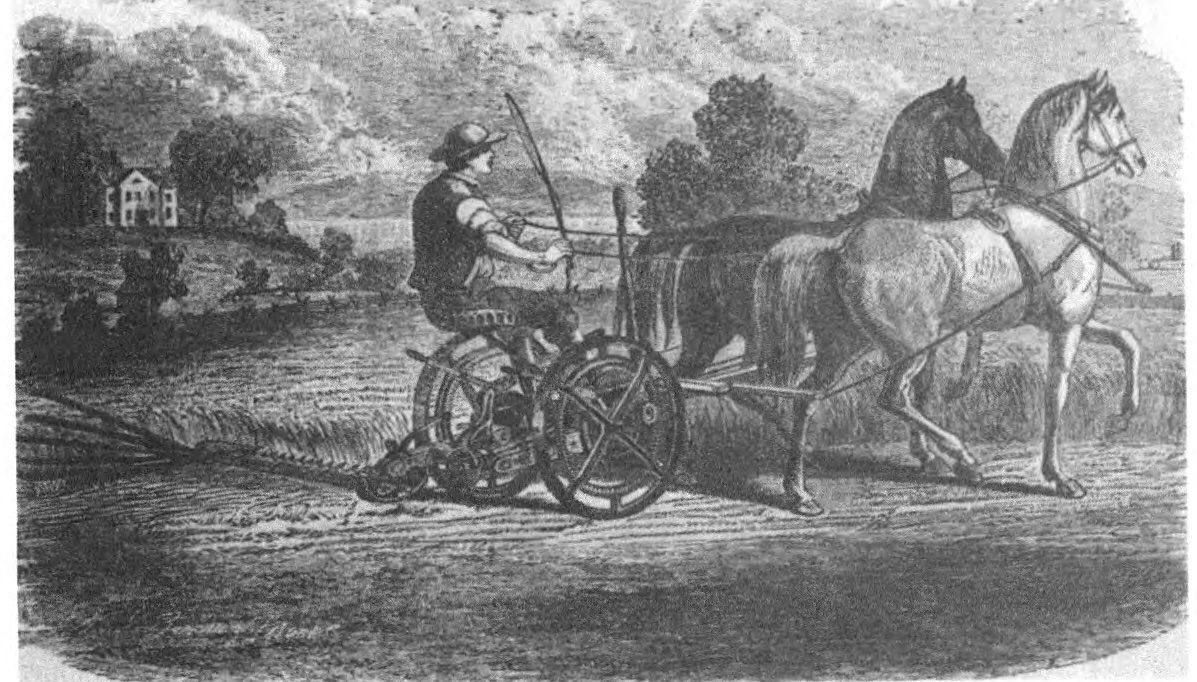

Warder became quite wealthy from his various enterprises. He was fascinated by the new hand-rake reaper emerging from Seymour & Morgan. For $30,000, Warder bought an interest in the Seymour & Morgan patents.

The business grew rapidly. During the early 1850’s, Warder associated himself with J. C. Child. Business was conducted as Warder & Child until January, 1866. Also, during the 1850’s, Warder & Child began building the Wright-Atkins “Automaton”, an early self-rake under a license from Seymour & Morgan.

Warder was one of the few men of his social status who served as a lieutenant in the Union Army. During his absence, the business was managed by Mr. Child, along with Ross Mitchell and J. J. Glessner. When this arrangement expired by limitation in 1879, the firm of Warder, Bushnell & Glessner was organized, with Mr. Mitchell retiring.

The firm of Hatch & Whitely was organized at Springfield, Ohio in 1852. Whitely built his first machine as a combined reaper and mower. It was 1854 before this outfit was placed on the market, but it was the basis for much of the “Champion” system that followed.

A partnership of 1856 resulted in Whitely, Fassler & Kelly. In 1860, this firm launched an unsuccessful at tempt to unite manufacturers to resist paying royalties and shop rights to Obed Hussey.

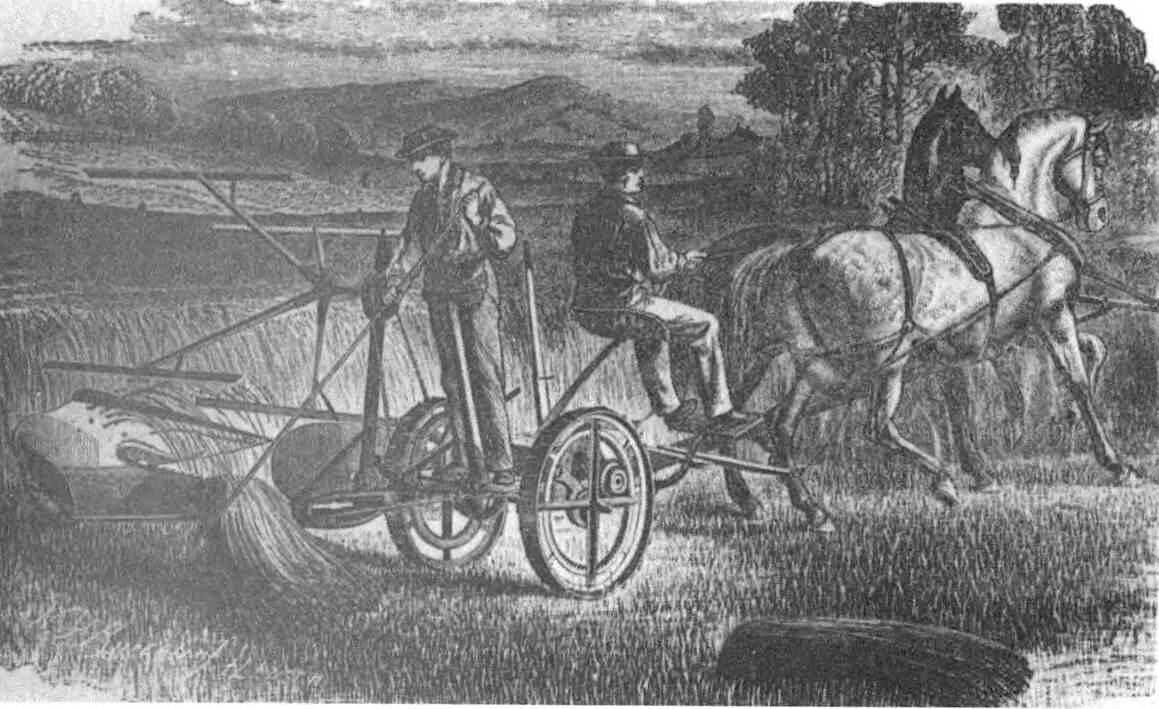

William N. Whitely could generally out-talk, out work and outwit any adversary. The feat that first made Whitely famous was performed in 1867 at Jamestown Ohio. A field competitor was doing as good a job as Whitely. Angered at this, Whitely un hitched one of his horses and finished reaping with but one animal. The competitor followed suit, and did just as well. Seeing himself bested, the enraged Whitely cut loose the remaining horse and pulled the reaper across the plot singlehanded. This amazing feat was witnessed by about five hundred farmers and was ful ly reported in the press.

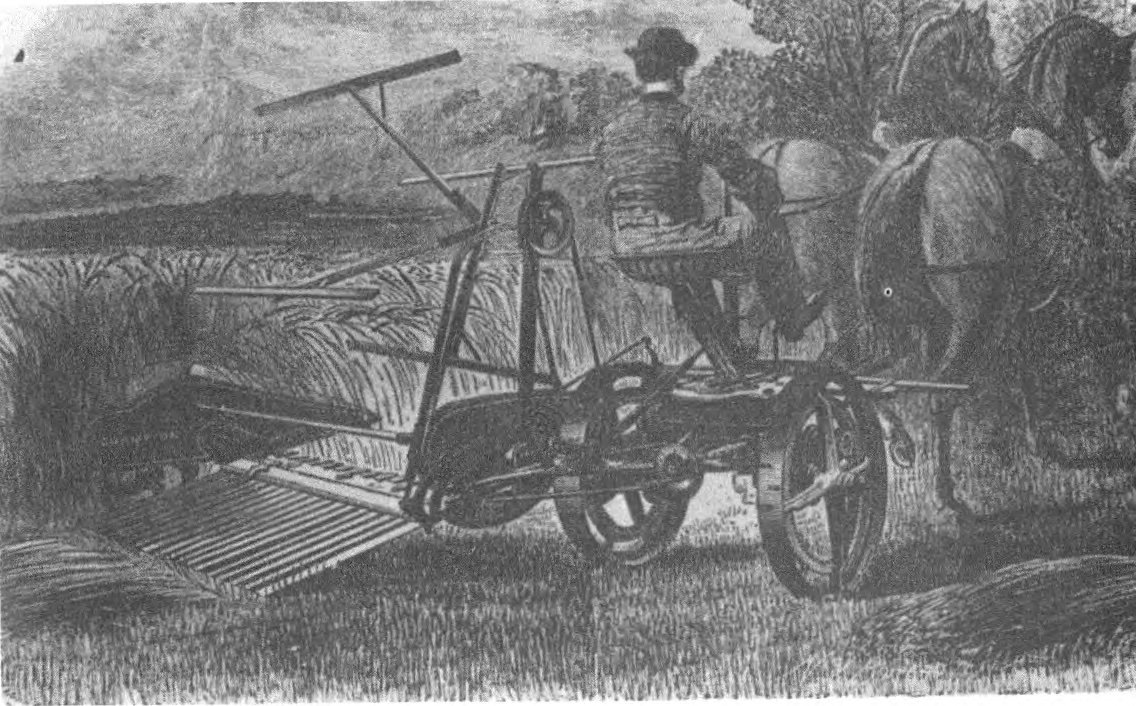

Whitely’s factory took an 1867 license to build the Johnston self-rake reapers. The keen competition be tween Whitely and Warder led to an 1867 consolida tion of the business whereby the territory was divided between these two companies. The Champion Machine Company was then organized to handle territory ced ed to it by the other two firms.

The consolidation greatly strengthened both com panies. Warder and his partners handled the business management of the three houses. Whitely headed the experimental work, and Fassler managed the factories.

Champion introduced malleable iron castings in its 1874 machines, followed shortly after by a reaper of all-steel construction. Throughout its years of opera tion, the Champion factories were renowned for high quality machines and excellent workmanship.

Whitely, Fassler & Kelly Company failed in 1887, and Champion Machine Company withdrew from the business. Warder, Bushnell & Glessner Company took over both firms. During the following fifteen years, the Champion line experienced steady growth. It was one of the five firms which formed International Harvester Company in 1902.