In 1852 John H. Manny Company was organized to build the Manny reaper. Two years later, in 1854, Manny built nearly 1,000 reapers. His small factory at Waddam’s Grove, Stephenson County, Illinois was overwhelmed by the demand.

Pells Manny and his son John began building reapers in the late 1840s after they had acquired an Esterley header. Beginning with a header of their own design, the father and son team soon discovered that the demand for these machines was very limited. By 1850 they were concentrating on a combined reaper and mower. This machine soon gained an enthusiastic welcome. Although this machine was somewhat like the McCormick reaper, it had many innovative features. These included a unique sickle and guard fingers.

Not content to allow Manny to go unchallenged, McCormick soon engaged him in field trials and ultimately to trials by judge and jury. When the New York State Agricultural Society held its Annual Fair at Geneva in 1852, Manny received first prize for his mower and second prize for his reaper. McCormick did not place in either class. In another trial the following year, the Manny reaper was the better, but he was bested by McCormick’s reaper-mower combination.

Sometime in late 1853 or early the following year, John H. Manny moved to Rockford, Illinois to organize his company.

Meanwhile, his father remained at Waddam’s Grove and continued to build a few machines at the home factory. During 1854 the Manny machines again triumphed over those of McCormick. This was too much to bear, and in November of that year, Cyrus McCormick filed a Bill of Complaint in the United States Circuit Court, charging an infringement by Manny of the 1845 and 1847 McCormick patents. In January of 1856 the Circuit Court ruled in favor of Manny. Shortly after hearing the good news, Manny died of consumption at Rockford, Illinois. McCormick was not content to accept the ruling of the Circuit Court and filed an appeal with the United States Supreme Court. In May, 1858 they upheld the Circuit Court decision and dismissed McCormick’s bill with costs.

After Manny’s death, two of his partners, Waite Talcott and Ralph Emerson, a cousin of the poet, took over the management of the Manny Company. The resulting firm was known as Emerson-Talcott Manufacturing Company. With the passing of Talcott, Emerson gained complete control and operated as Emerson Manufacturing Company.

Emerson was born at Andover, Massachusetts in 1831. Barely into adulthood, he was already teaching school and studying law. At age twenty he located at Bloomington, Illinois, and a year later he opened a retail hardware store in Rockford. About this same time he invested in the Manny venture. Due to the tremendous success of the Manny machines, Emerson soon sold the hardware store and went into the manufacturing business.

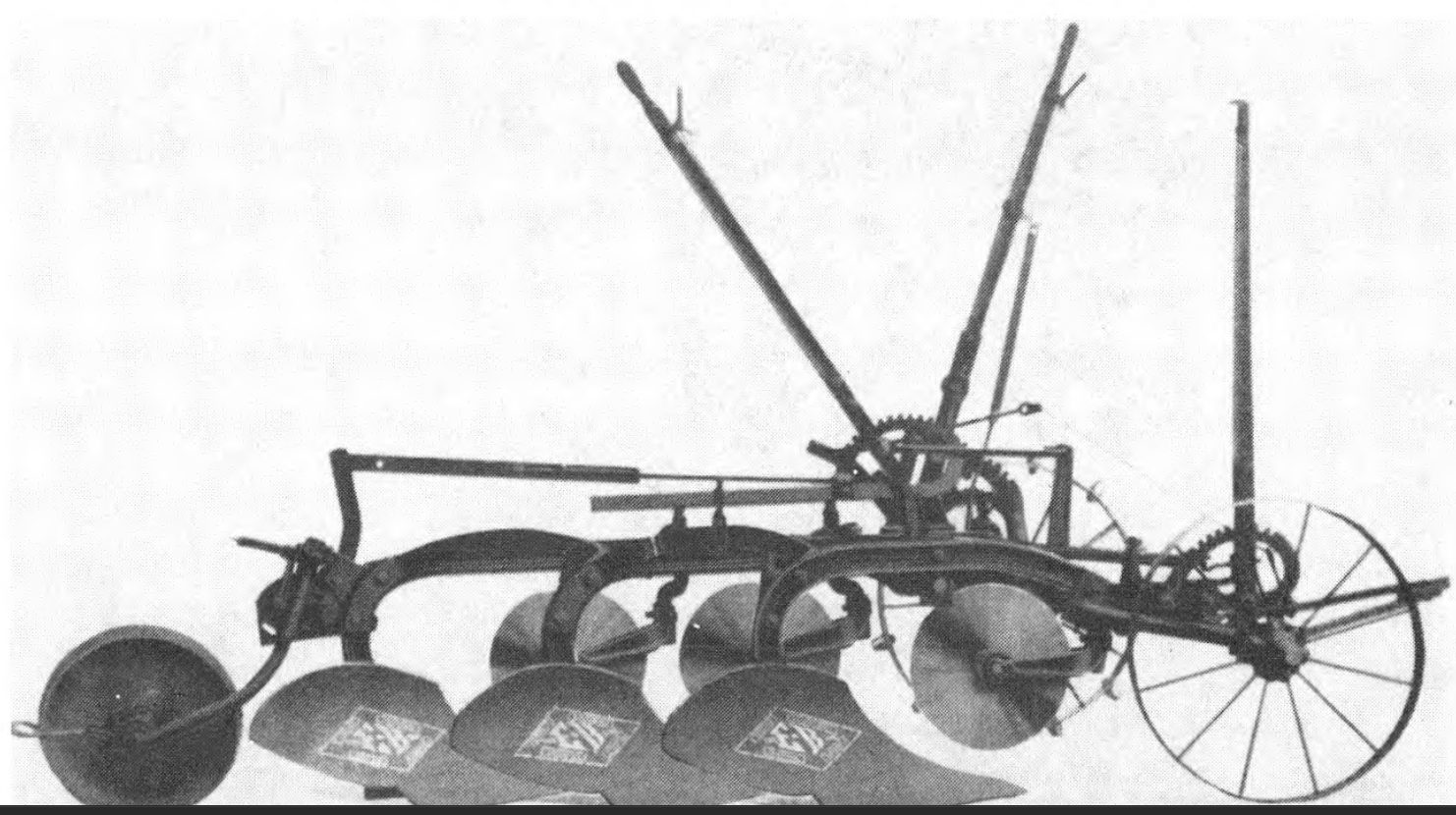

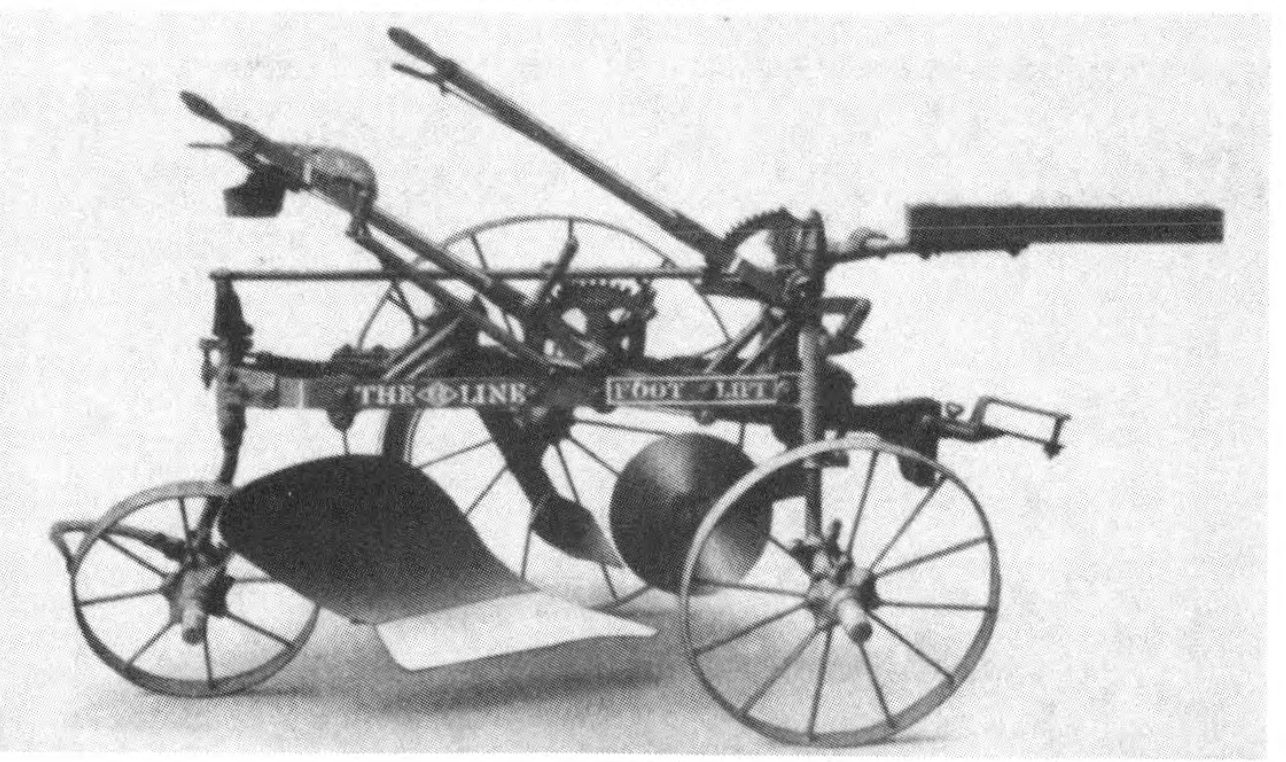

Emerson Manufacturing Company quickly rose to national and international prominence, not only with mowers and reapers, but also with plows and tillage implements. Mr. Emerson’s business acumen and the development of a nationwide dealer network kept the Emerson name in evidence, and in fact, the Emerson line was highly respected wherever used and sold.

Charles S. Brantingham worked his way through the ranks to become president of the company in 1909. That same year the firm was reorganized as Emerson- Brantingham Company. Brantingham was not at all related to the Emerson’s, but the Emerson family was so impressed by his abilities that he was, more or less, hand picked for the job.

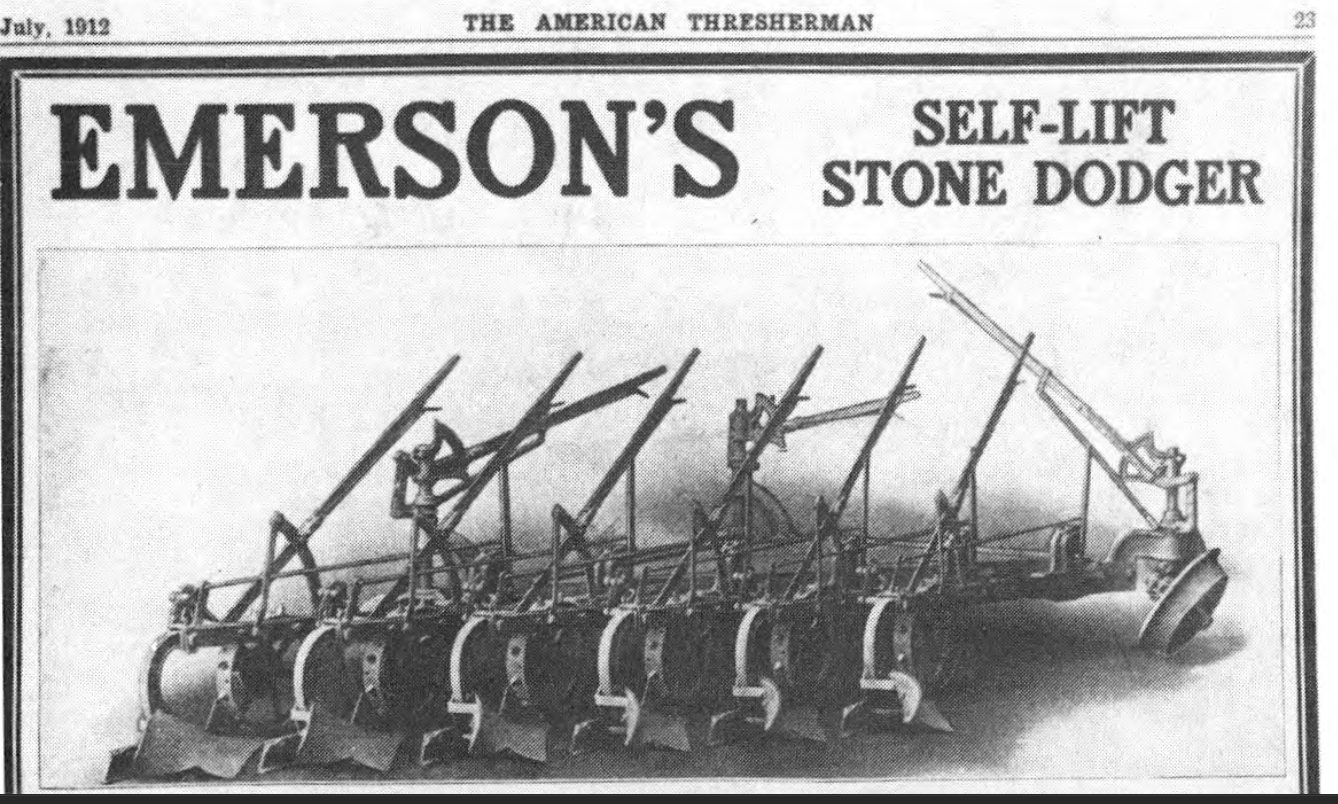

Under Brantingham’s leadership the company prospered at first. Like Case, International, and others, EB caught a case of expansion fever. This culminated in 1912 with the purchase of several large firms. These included: Reeves & Company, Columbus, Indiana; Rockford Engine Works, Rockford, Illinois; Gas Traction Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota, (including their “ Big 4” Tractor Works at Winnipeg, Manitoba); Geiser Manufacturing Company, Waynesboro, Pennsylvania; and several smaller firms.

Reeves was one of the old-line steam engine and thresher builders, as was Geiser. Through the buyout, E-B gained steam engine and thresher lines. Rockford Engine Works was well established with its excellent line of stationary and portable gasoline engines; this gave E-B a gas engine line. Gas Traction Company was one of the pioneer builders of farm tractors, and thus the E-B line was now virtually complete with everything from plows and tillage equipment to tractors and threshers for the harvest. In some respects, E-B bought more wisely than their competitors. The Big 4 tractor line from Gas Traction was well known, and the Reeves and Geiser lines were both of the highest credentials. In fact, the Reeves tractor remained in the E-B line for some years, although it does not appear that a great number were sold.

Emerson-Brantingham fell into hard times by 1915. The market for heavy tractors was collapsing under its own immense weight, and sales of steam traction engines were beginning to sag. The advent of small and lightweight tractors was throwing the industry into a tizzy, making the heavyweights almost impossible to sell, except to the large prairie areas. For the average 80 or 160 acre farm, these tractors were virtually useless—many farmers didn’t have a field big enough to turn around with one of these behemoths!

In 1916 E-B presented its first original tractor design. It was the Model L, rated at 12 drawbar and 20 belt horsepower. Its three-wheeled design with a single rear driver was no more unusual than the competing Bull tractor and its clones, yet sales were not very exciting. The following year however, E-B presented its Model Q, 12-20 tractor. With a few changes, it remained in the line until J. I. Case took over E-B in 1928. Numerous other models were presented in the interim, including the No. 101 motor cultivator in 1923. By the time of the Case takeover in 1928, E-B had not yet presented their version of a row-crop tractor to the farming public, although there may have been some experimental work following the motor cultivator.

For J. I. Case, the E-B acquisition marked a major step forward in expansion of the product line. Although the Grand Detour line acquired in 1919 had given Case its own line of plows, the tillage implement line was still deficient. Also acquired was the E-B line of mowers, grain binders, and hay equipment. For many years, the E-B plant was known as the Rockford Works of J. I. Case Company.

Through extraordinary circumstances, E-B acquired the famous Osborne implement line in October 1918. International Harvester had quietly purchased Osborne in 1903. However, the endless series of suits brought by the United States Government against International Harvester under the anti-trust laws, would continue for many years to come. Finally, a settlement was reached whereby IHC divested itself of the Osborne line, and it was then purchased by Emerson-Brantingham.

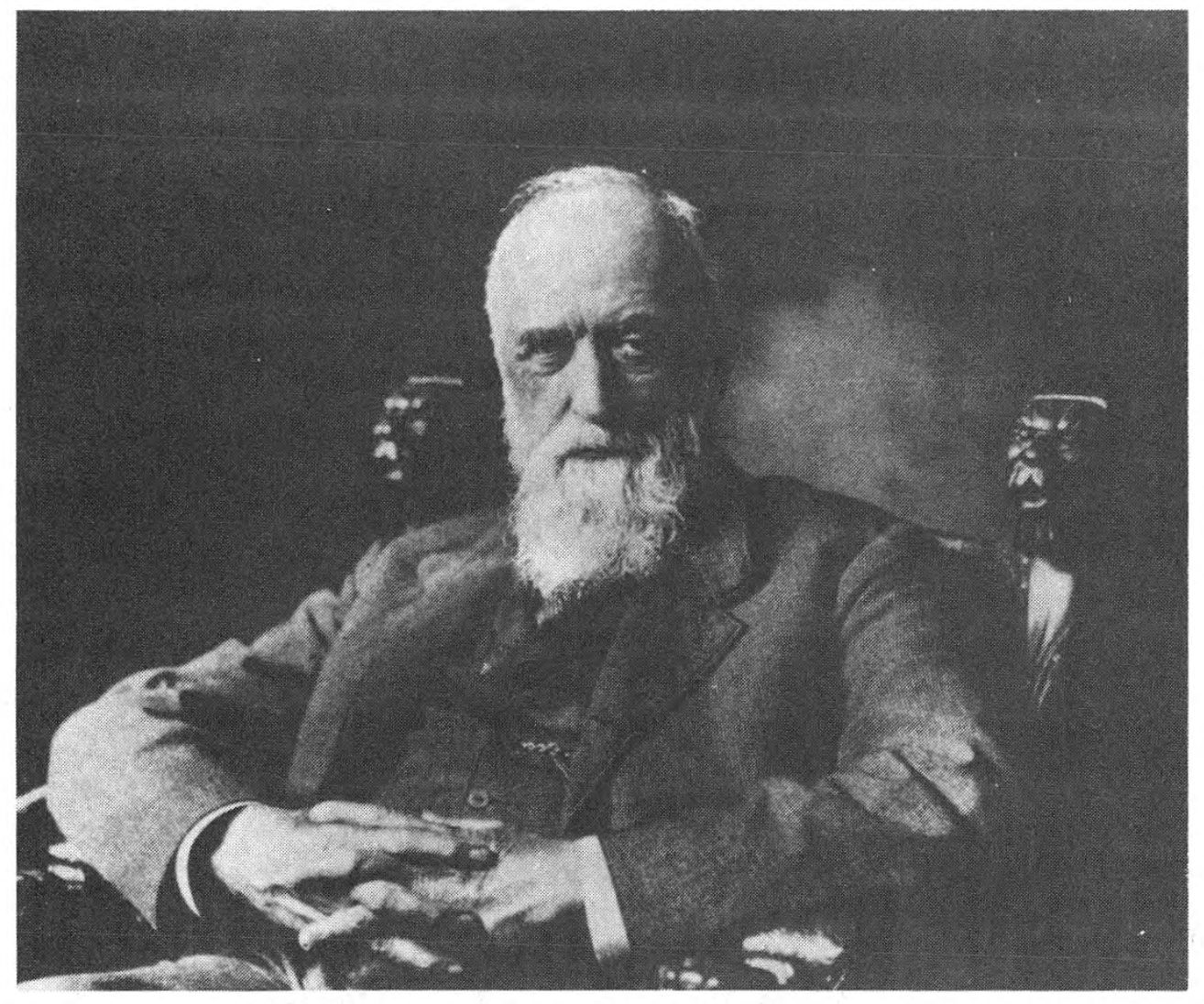

David Munson Osborne was born at Harrison, Westchester County, New York in December of 1822. After the death of his father in 1841, Osborne remained on the family farm until 1843. At this point he began clerking in a New York City hardware store. During 1848 he moved to Auburn, New York, assuming the position of junior partner in Watrous & Osborne, manufacturers of hardware and farm implements. Eventually the firm took the name of Osborne, Baker & Baldwin, and finally in 1859 it was reorganized as D. M. Osborne & Company.

Osborne was a leader in the development of mowers and reapers, and proved to be a continuing competitive pain in the side to Cyrus Hall McCormick. During the 1870s and 1880s the McCormick’s were building grain binders of a design contended to be an infringement on the Gordon patents. Osborne had, by this time gained effective control of these patents, and, as might be expected, a suit for recovery of past royalties ensued. Late in 1884 a settlement was reached whereby McCormick agreed to a settlement of $225,000 in past royalties, while the patent holders agreed to refrain from further litigation in the matter. However, the McCormick’s were reluctant to write a check for this amount, fearing that it would be photographed and published all over the country. Instead, Osborne and his associates were asked to come to the McCormick offices after working hours, and of course, after the banks had closed for the day. There they were presented with $225,000 in small bills. The counting alone took several hours, and then came a scary trip through dark streets as they returned to their hotel.

Along his way, Osborne was fortunate enough to seize on an opportunity of the Cayuga Chief line. Originally organized as Barber, Sheldon & Co. during the 1850s, this implement maker evolved into the firm of Burtis & Beardsley in the 1864-66 period. At that time Cyrenus Wheeler Jr. took over and renamed it as Cayuga Chief Mfg. Company. During 1875 Osborne acquired Cayuga Chief and reorganized the firm as D. M. Osborne & Company with a capitalization of $750,000. During this period, Osborne hired approximately 1200 men, and was by far, Auburn’s largest industry. By the time Osborne died in 1886, his company was producing in excess of 30,000 mowers, reapers, and other machines each year.

The Osborne line was beneficial for International Harvester in that it provided them with an excellent eastern factory, shipping point, and parts depot. The previously established Osborne export connections, especially to the European companies enhanced Harvester’s position in the export market. After the sale of Osborne to Emerson-Brantingham, they too reaped these same benefits. Additionally, the Osborne line was well received with farmers. Thus, the E-B Osborne line continued, and in fact, after Case bought out E-B they continued with selected Case-Osborne machines for a few years.

Moody’s Industrials for 1924 gives some indication of the company’s financial position. For instance, dividends were paid on the preferred stock between 1912 and 1914, but none were paid until after November 1918, and then only a portion of the accrued earnings. Small amounts were paid on the preferred during 1919 and 1920, but none were paid thereafter. Apparently, no dividends were paid on the common stock during this entire 1914-1924 period. In fact, there were no earnings to share in the panic-stricken years of 1920-1924. Revery after that time was meager indeed, and this made E-B an excellent takeover prospect. J. I. Case Company came along, and that is exactly what happened.