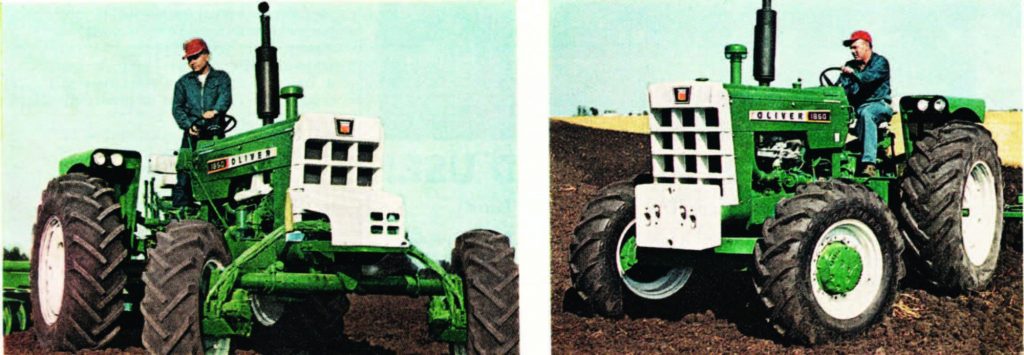

Nice Day, nice field, nice tractor. What’s not to like?

It wasn’t hard to spot the big Oliver 1850s when they were hunkered down and working hard. Tommy Cannon from South Fulton in northwestern Tennessee remembers his father’s 1850 “really put out the smoke” when under a full load and Sean Overmyer of F.L.G. Overmyer Farms in Culver, Indiana remembers plowing fields at night and “watching the top of the stack get cherry red from pulling the six bottom plow.”

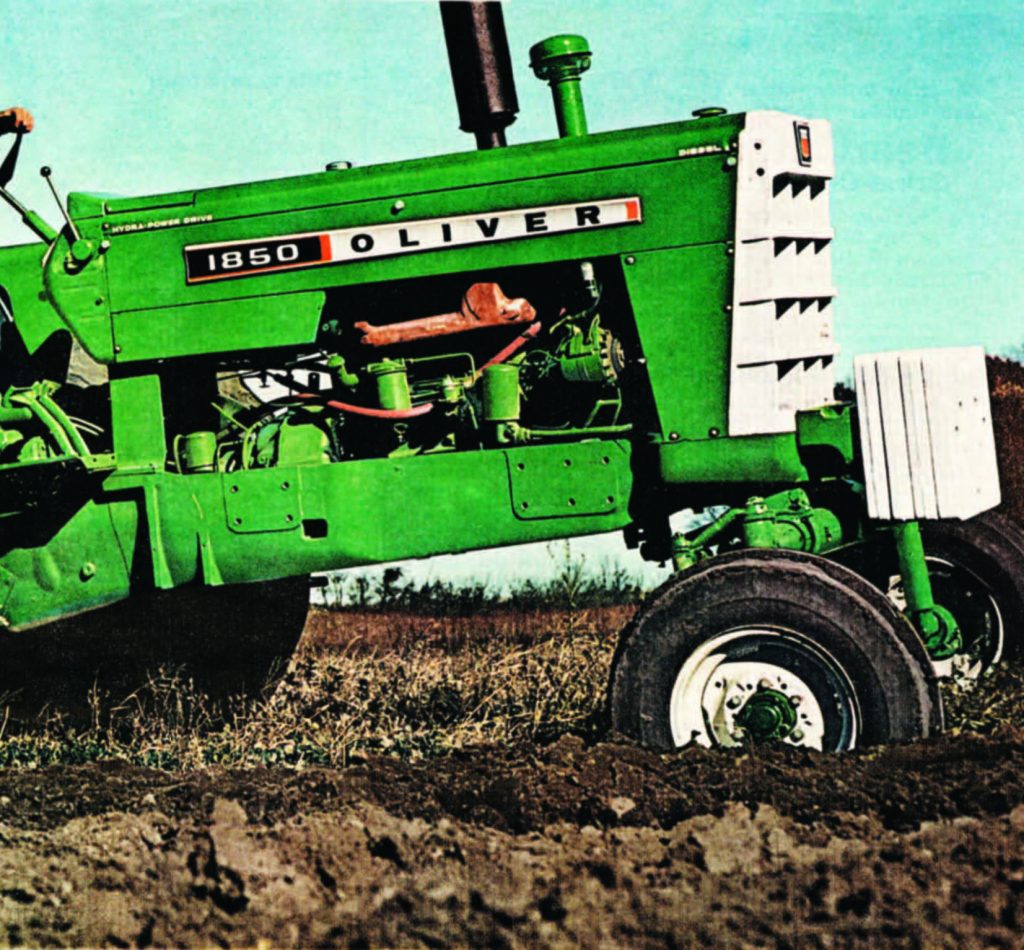

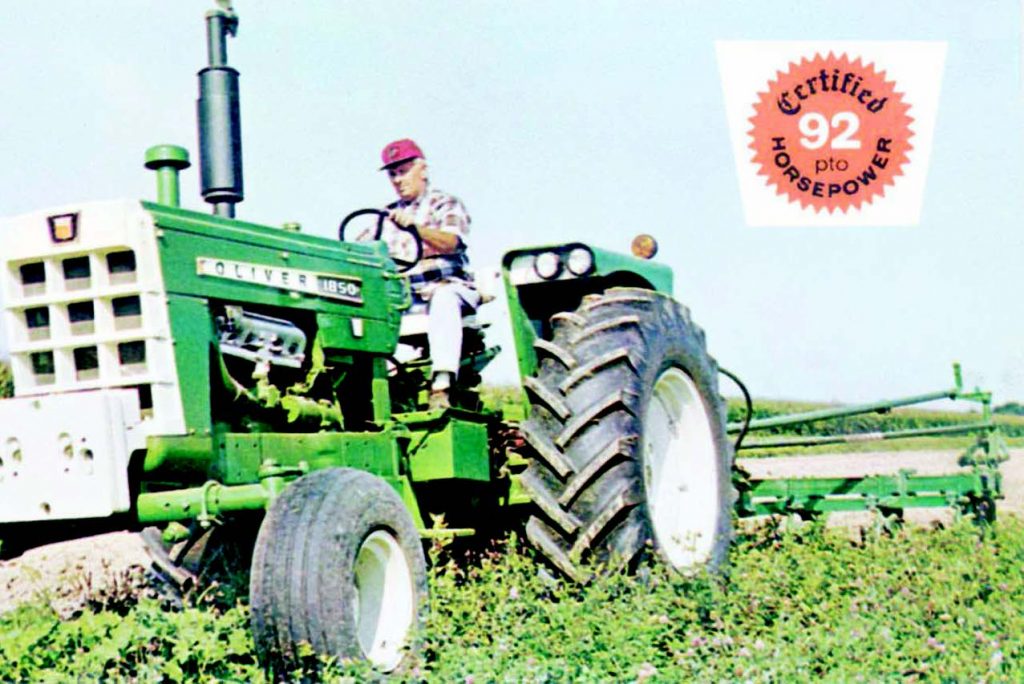

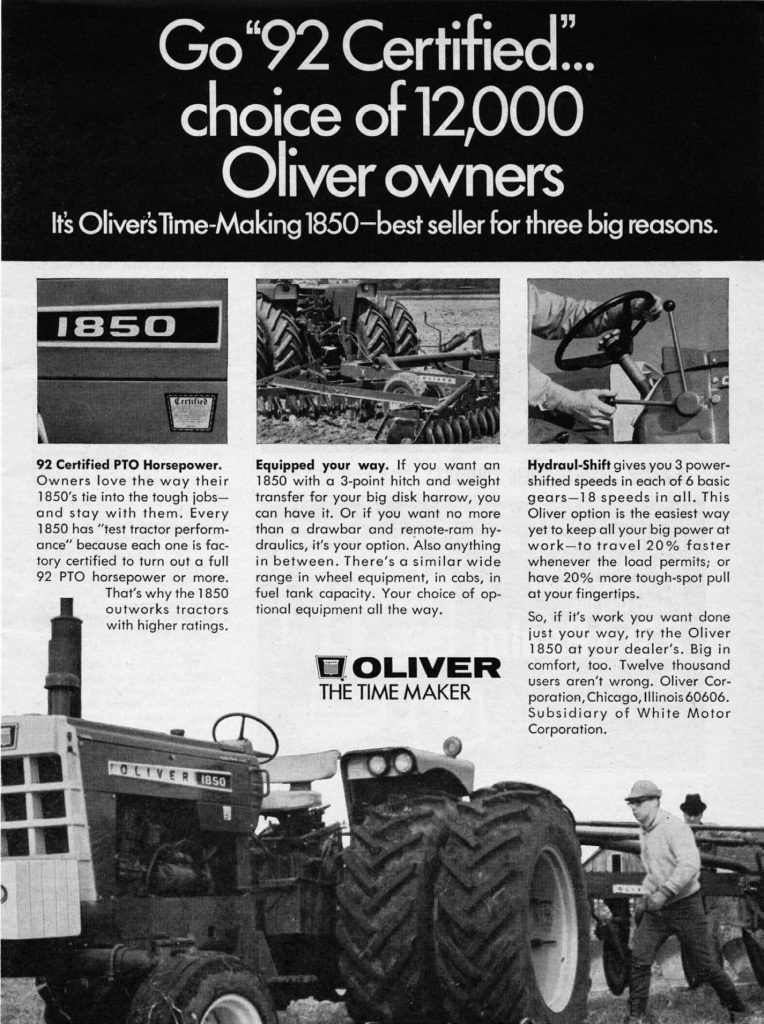

Pointing out the power of the 1850 was something Oliver Corp. did every chance it had.

“Notice the heavy, massive look, the impressive commanding style of an Oliver 1850 which has been designed to ‘Mighty Power’ standards…”.

That was part of the suggested sales pitch Oliver dealers received from corporate headquarters in November 1964 as the company rolled out “new for 1965” the 1650, the 1850 and the 1950. The new Oliver tractors were sold with the guarantee of “certified horsepower,” meaning every tractor was certified to deliver no less than its rated horsepower.

The 1850 diesel was rated at 81.76 horsepower at the drawbar and 92.94 horsepower at the power take-off unit.

“Back in its day, not many neighbors would try to outdo our 1850 with any other brand because they would be disappointed,” recalled Cannon.

Cannon was 16 years old in April of 1967 when Dunnavant Tractor Co. delivered his father’s new 1850.

“It was a diesel with the short wheelbase (under-slung) front end,” said Cannon. “It was the only one they ever sold with that front end. They delivered it with a five-bottom, 14-inch, semi-mounted plow. They had all the weights on the front end that they put on the regular row crop tractors.”

But all that weight proved to be too much. Not for the 1850, but for the ground Cannon’s father was working.

“Daddy was plowing soil bank land that he had bought a couple of years earlier and when he got on seepy hillsides, the front end fell through and he was stuck and had to be pulled out,” remembered Cannon. “After a few hours of this, they started taking off weights down to a base weight and one slab weight. It originally had the base weight and three slabs plus water in the tires. After the weight reduction, it worked just fine. To this day, the tractor has never had all the weights on it.”

The 1850 was built from 1964 through 1969 with a total output of 66,966 units, making it one of the higher production Olivers from the late 1960s. Production started at 2,592 in 1964 and climbed steadily through 1967, with 14,271 tractors built in 1965, 15,254 in 1966 and 16,582 in 1967. Production dropped to 12,086 in 1968 and 6,179 in the final year of 1969.

Overmyer was born about the time his father bought their 1850 in 1968.

“I wasn’t allowed to drive the tractors until I turned 13 but I can remember those long days pulling a six-bottom plow with the 1850, side-dressing corn, baling straw, and cultivating,” said Overmyer. “Sometimes we slapped on the duals and put the 15-foot, three-point hitch chisel plow on it or disk—that was back when we farmed over 1,200 acres.”

F.L.G. Overmyer Farms believed in Oliver horsepower.

“We had an 1850, an 1855, a 2255, a (White) 2-105, and a 4-180,” said Overmyer. “We still use the 1850 today on the farm, drilling (soy)beans and hauling wagons from the field.

“Last year we used it to plant corn. It pulled an eight-row, 38-inch row very easily. We just last year overhauled the Perkins diesel for the first time since owning it. That tractor has seen a lot of acres over the last 37 years.”

Oliver built the 1850 with an “ultra-modern” diesel engine, which, the company pledged, combined “dependability with dollar-saving economy, whether it’s lugging or loafing.”

And the 9,270-pound Oliver 1850 could lug. Prospective buyers were told the power of the 1850 would enable them to think in terms of larger equipment, to operate more cropland acres, to do more work each day.

The 1850 was offered with Perkins diesel or LP gas or gasoline engines, all six-cylinder Waukesha units. All three engines had a governed speed of 2,400 RPMs. The diesel piston displacement was 352 cubic inches, while the gasoline and LP models were rated at 310 cubic inches.

The power from the engine was transferred to constant mesh, helical geared transmissions. The standard transmission came with six forward and two reverse gears. The optional hydra-power drive permitted each gear to be downshifted on the go for a total of 12 forward speeds. In 1967, the hydraulic under-direct-over shift was introduced and the 1850 became an 18 forward and six reverse speed tractor.

Fuel was drawn from a standard 34.5 gallon gasoline, 31.5 diesel or 42 LP gas tank. Optional equipment for the 1850 included fender-mounted fuel tanks. Each extra fender tank could hold another 39 gallons.

Oliver was proud of the diesel engine, which it called the “Dyna- Diesel,” a revolutionary engine introduced to the tractor industry through the 1850.

“The heart of any diesel is the fuel injection equipment,” Oliver told its dealers. “A high-speed rotary injection pump meters fuel to each injector which is located in the cylinder head. One basic calibration assures even fuel distribution to all cylinders. No need to calibrate and phase each cylinder because phasing is automatic.”

Dealers in turn told their customers: “Injections, under normal conditions, will last the lifetime of the engine, but should you need to replace one, it will be a simple operation. They can be replaced in a few minutes without delicate adjustment.”

The 1850 row crop could be equipped with either dual front wheels or an adjustable front axle to meet the needs of row crop farming. Oliver also offered the 1850 in the wheatland and ricefield models, which were tailormade for grain, rice, and other large acre operations. A four-wheel drive for both the agricultural and industrial models also was available.

Oliver sales literature said the four-wheel drive 1850 provided effective weight distribution on all four driving wheels, reducing slippage and compaction, and increasing traction under all working conditions.

One-third of the engine torque was applied to the front wheels to power tractor and equipment through tough spots and relieve the rear axle load.

The four-wheel drive unit came in two options. The first was the mechanical front drive with a fixed tread axle with widths of 66, 70.75 or, with special spacers, 80 inches. The second option was the variable hydraulically-powered front wheel drive with an adjustable axle to match row spacing.

The wheatland and ricefield versions were heavy-duty, compactly designed tractors with relatively short wheel bases for better maneuverability. The wide-wheel guards were designed to protect the operator from dust, dirt, flying mud, and objects thrown by the rear tires.

Cannon said his family’s tractor was used for a variety of chores.

“The 1850 was used to plow, disk, chisel, and cultivate,” said Cannon. “It was used a little bit to rake hay. In the 1970s, we put in a silo and it was used to cut silage.

“I loved to cut silage with it because you ran the motor wide open for rated PTO speed, but that was a drawback for other PTO work. If you didn’t need the power, you still had to listen to the motor scream.”

The 1850 came with a heavy-duty three-point hitch to accommodate category II and III implements. Extra lift capacity—6,000 pounds 24 inches beyond the rear end of the lower links—also was available. Lift was operated by two-single acting, three-inch external cylinders hooked in parallel.

Lower-link draft sensitivity and a double-feedback system held implements at a uniform depth and external variable-rate leaf springs provided the correct amount of draft sensitivity automatically.

“The only problem we had with the tractor was it busted a bull gear,” said Cannon. “Evidently, Oliver had a bad batch of these gears. The only other problems we had were with the front end. In my opinion, it wasn’t heavy enough for the tractor. We broke several pitman arms and at least one spindle.

“It had the hydroelectric remote cylinders and if everything was perfect, it was wonderful, but we had trouble keeping the electric cord in shape.”

Operator comfort was a selling point for the 1850. Oliver deemed the seat on the 1850 “comfortable, restful, adjustable and convenient.” Oliver dealers followed the corporate pitch with their own, adding: “None of those words adequately describe the experience of sitting on the new Oliver seat and this new seat, which offers so much extra personal comfort, is standard equipment on the 1850 tractor.”

The seat was mounted on an inclined slide rail, which allowed the seat to slide up and back to suit the needs and comfort of the operator. It also permitted the operator to stand on the platform with ease. Armrests were incorporated into the backrest but did not restrict operator movement.

Oliver claimed its exclusive “tilt telescope steering” added to operator comfort and ease.

Engine adjustments and servicing of the dry air cleaner were made easier by the 1850’s new hood side panels which could be removed by loosening three thumb screws.

The 1850 also could be fitted with a contour-tailored Oliver Continental cab for the row crop and wheatland models. The cabs used a “pressurizer” with an overhead blower to 400 cubic feet of fresh air into the cab every minute. The sun-reflecting roof was insulated with fireproof, closed-cell polystyrene. Tinted safety glass and exhaust extension were standard with the cab.

Overmyer, though, prefers to work with the 1850 in the open air.

“I really enjoy the cabless 1850 for its ease from getting on and off the tractor,” Overmyer said.

Both Cannon and Overmyer plan to hang on to their 1850s.

“Daddy and I divided up farming in 1978 and he kept the 1850 and didn’t do much with it,” explained Cannon. “He rented his land out in 1989 and the 1850 set up in the shed until 1995 when he sold the rest of his equipment.

“He gave me the 1850 and we used it around our farm, but it never ran well since it sat so long. In the fall of 2002, it lost oil pressure while we were disking up corn stalks. The next spring, we started working on it. We completely went through the motor, fixed the oil leaks, changed the front end to a row crop-wide front, and painted it. We even replaced the seat cushions.

“We still don’t use it for much because we no longer row crop—we just raise hay. Most all of our work is PTO and I don’t like the running the motor that fast when I don’t need the power.”

Cannon also has three Ford tractors he uses in the hay business.

“But I still love to crank up the 1850 and use it when I can,” said Cannon. “I also carried it to a couple of shows. I also carry my 1949 model 77 Oliver.

“I was 16 when the 1850 was bought and I hope my kids will keep up with it after I’m gone.”

Overmyer doesn’t see his 1850 leaving any time soon, either.

“My grandfather farmed all of his life and was still farming at age 92 when he had a fall and passed away,” said Overmyer. “He had an attachment to the 1850 and did not want to sell it.

“All we have now is the 1850 and the (White) 2-105. I don’t think I would change a thing on the 1850— maybe headlights in the grill like the 1855 had—but it’s been a very durable and reliable tractor. We could always count on that tractor starting.”