As with the Cockshutt line, the Minneapolis- Moline line had no connection with Oliver Corporation in the strictest sense. The commonality lies in the acquisition of Minneapolis-Moline, Cockshutt, and Oliver by White Motor Corporation in 1969. These companies were acquired by the parent White Motor Corporation as wholly owned subsidiaries and merged to form the White Farm Equipment Company. Headquarters were at Oak Brook, Illinois. White Farm Equipment functioned as a division of White Motor Corporation. Ironically, Oliver had acquired the Cleveland Tractor Company some years earlier; it had its beginnings with Rollin H. White, also of White Motors.

A pictorial history of Minneapolis-Moline was published by Motorbooks International in 1990 by this Author. Although it is not a comprehensive, in-depth study of Minneapolis-Moline and its ancestors, it does provide a thumbnail sketch of the company, particularly regarding its tractors.

Minneapolis-Moline began in 1929 with the merger of three companies; Moline Plow Company, Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company, and the Minneapolis Steel & Machinery Company. Each had in its own right established a brief niche in the farm equipment industry, and each had made its own contributions.

A significant development of Moline Plow Company was their Moline Universal tractor. It represented a radical departure from usual practice, in that the drivewheels were in the front, with the implement attached to the rear of the tractor. This concept of an integral tractor and its implement was not new, but Moline developed it to an extent that was previously unheard of. Despite its brief popularity, the Moline Universal lasted for only a few years, after which Moline Plow retreated to manufacturing implements, never again entering the tractor business.

Regarding the Moline implement line, it is worthy of notice that Flying Dutchman implements were well received and enjoyed a wide market. Yet, by the 1920s, the implement market was changing. It was saturated with horsedrawn implements. The fact was that few farmers went out to buy a new cultivator every few years; the one they bought twenty years earlier was probably still cultivating the same fields in the same time-honored way. Changing over to tractor power required new implements, tailored especially for the purpose, and this was an intensely competitive market. Thus, Moline Plow found itself in tight financial straits by the late 1920s.

Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company offered an excellent line of threshing machines and had even made pioneering efforts in the combine business. Their tractors were equivalent to most others of the time. Yet, Minneapolis was not a full-line builder. Threshing machines, corn shellers, and tractors comprised the bulk of the Minneapolis line. By the 1920s the farm equipment industry had changed. Instead of a host of specialized concerns or short-line companies, the trend was toward full-line dealers who could offer everything needed on the farm under the same trademark. Thus, Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company was in difficulty by this time.

Minneapolis Steel & Machinery Company, like the other two partners, found itself in fierce competition for the available tractor sales by the late 1920s. Undoubtedly the Twin City line of tractors and threshing machines was among the finest in the industry. Yet, sales of new threshing machines were slow. The market was saturated, and replacement machines sold at a far slower pace than during those wonderful years when almost any threshing machine could be sold at almost any time. Again, the Twin City line was limited to a few items, and again, combining the effort seemed to be the only possible choice.

Ironically, the Minneapolis-Moline merger occurred in 1929, the same year as the Oliver-Hart- Parr merger. For Minneapolis-Moline, the merger provided a new lease on life, and in fact, gave the company another four decades of useful activity. During these forty years, Minneapolis- Moline pioneered numerous innovations in the farm equipment industry, one notable example being the development of propane equipment for tractors and its practical application thereto. For about five years following the 1969 acquisition of Cockshutt, Minneapolis-Moline and Oliver, the White Farm Equipment Company offered tractors under the individual trademarks. However, the tractors were the same. For instance, the Oliver 2055 and the M-M G1050 were the same. Another example is the Oliver 1265. It was also sold as the White 1270 and the M-M G350. Eventually, the silver and gray finish of a new tractor series appeared, and with its inception the Prairie Gold of the M-M line disappeared.

Beginning in 1969 the following tractor models were essentially the same, except for colors and decals:

White-Oliver 1555 and M-M G-50

White-Oliver 1655 and M-M G-750

White-Oliver 1855 and M-M G-940

White-Oliver 1755 and M-M G-850

White-Oliver 1865 and M-M G-950

White-Oliver 2055 and M-M G-1050

White-Oliver 2155 and M-M G-1350

Oliver 2655, M-M A4T and White Plainsman

Oliver 1265, White 1270, and M-M G-350

Oliver 1365, White 1370, and M-M G-450

White 1870 and M-M G-955

White 2270 and M-M G-1355

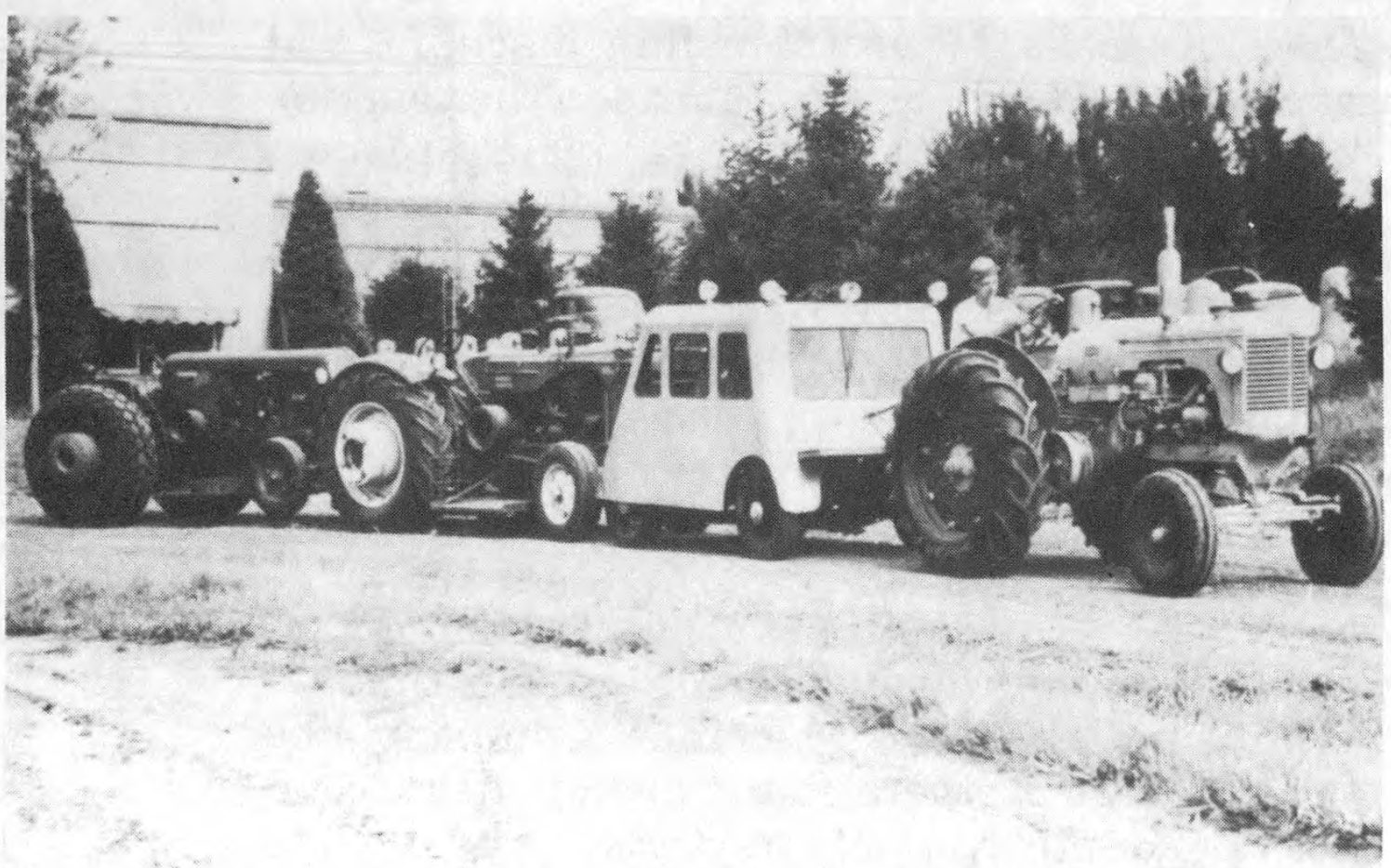

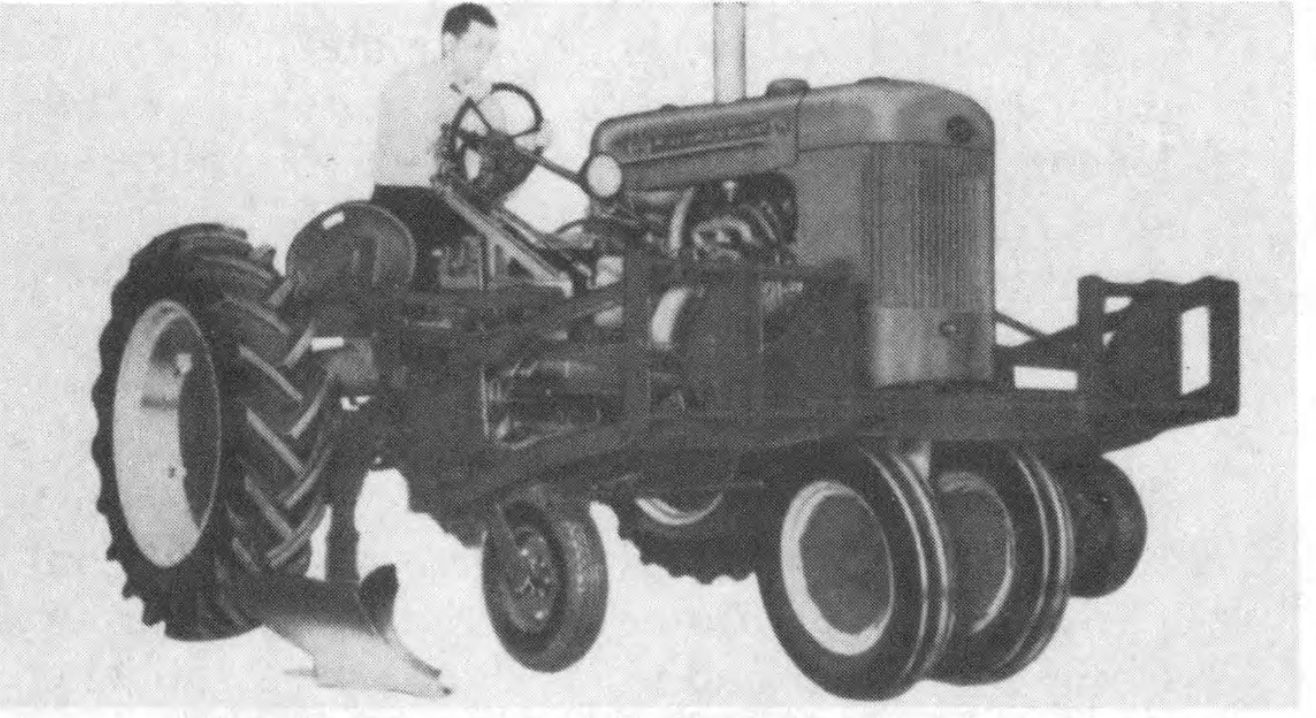

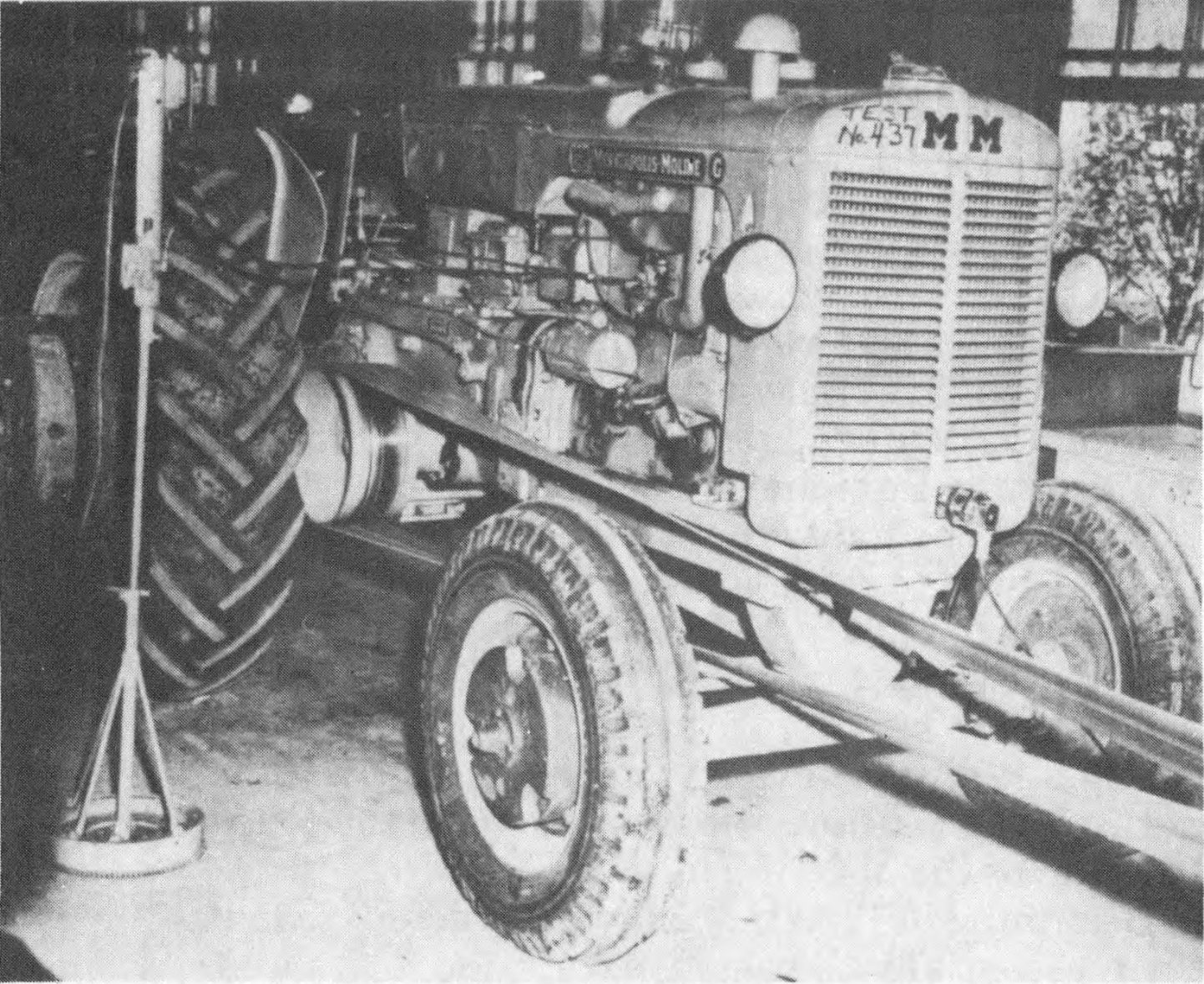

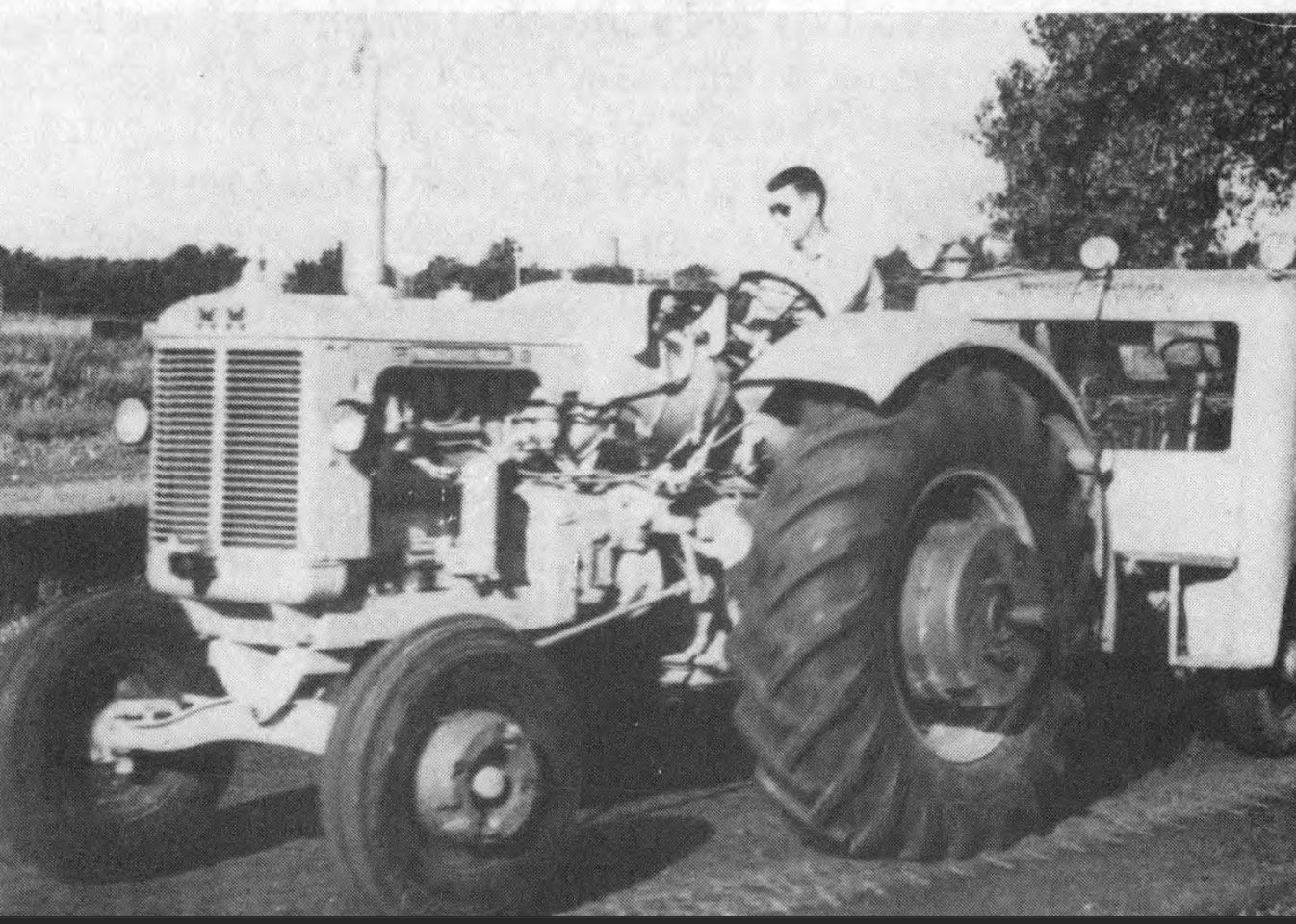

The photographs and captions accompanying this section present only a brief highlight of Minneapolis- Moline tractor activities during their 1929-69 operating period. A comprehensive look at this company and its ancestors is beyond the scope of this book.