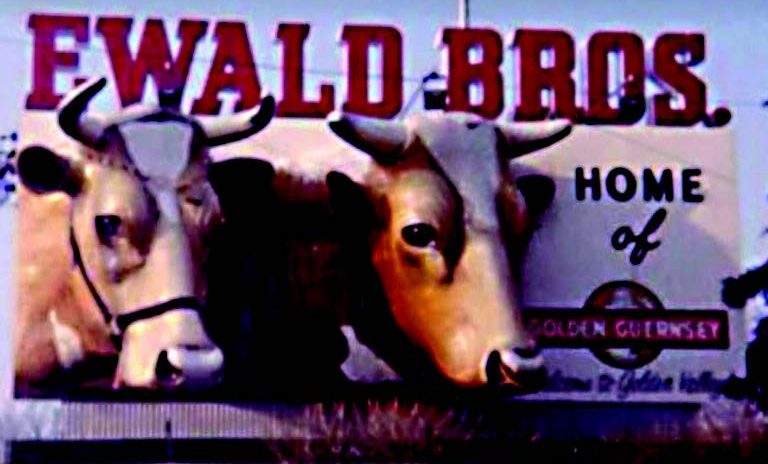

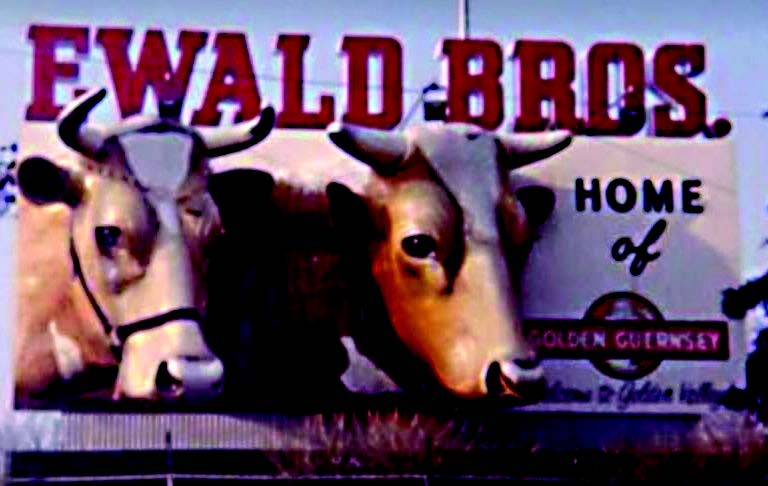

For many years, this sign (below) would greet those who entered Minneapolis, Minnesota on one of the main thoroughfares. The sign’s three dimensional Guernsey heads are still fresh on the mind of many a young person who grew up there in the decades around the 1960s!

Until 1982, Ewald Bros. Dairy was one of the largest dairies in Minneapolis with a large fleet for home delivery needs. Ask a city kid what a milk truck is and he’ll tell you about those medium-duty delivery trucks that make frequent stops at homes and stores in cities. In warmer weather, the driver goes down the street with his cab’s side doors wide open and, at each stop, he turns and disappears into the back, emerging with his carry basket and its assortment of bottled milk and other dairy products. But ask any kid who has lived in the country what a milk truck is and they might describe a large truck with either an insulated box or a tank behind the cab that stops at farms and backs up to the barn or milk house

In the last issue, the dairy farm, milking cows and the changes in that way of life were examined. This is the second part of “Milk: From farms to creameries” and we’ll take you from the milk can or bulk tank to the table—all a part of “Our Changing Americana.”

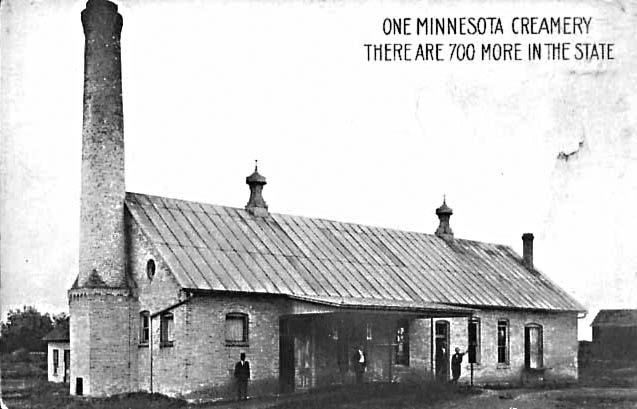

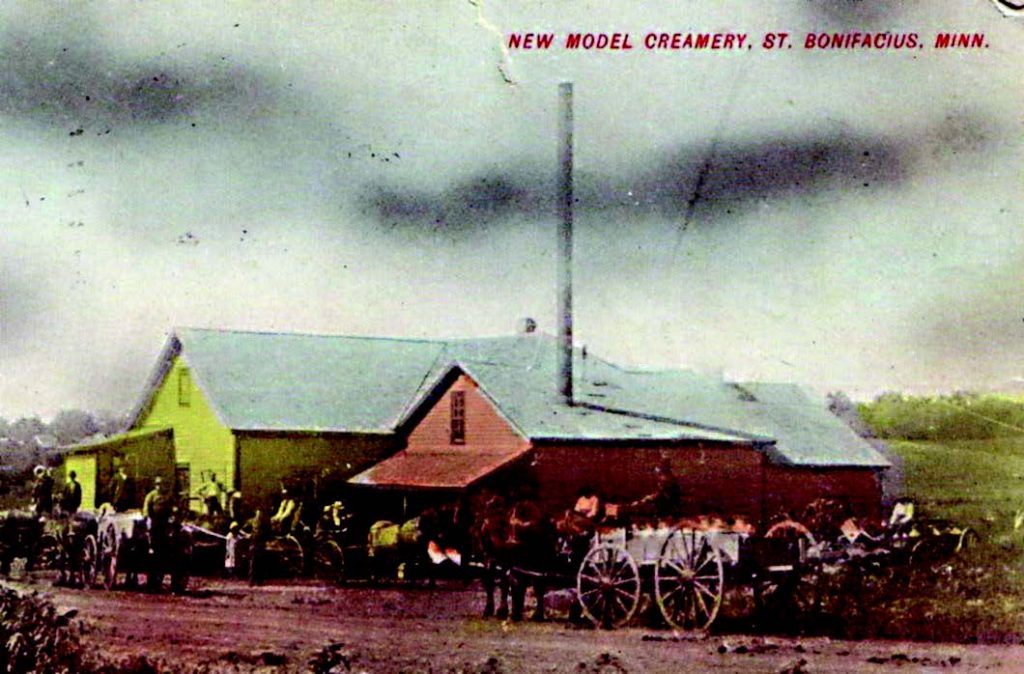

The caption on this 1910 postcard (below) says it all—over 700 creameries in Minnesota. In fact, most prominent dairy areas, like the midwest, had towns with even multiple creameries in a close proximity for farmers to deliver their milk. Many of those were even smaller buildings than the one shown. As the early years of the 1900s went on, smaller creameries were absorbed by others or simply went out of business. Even now, as I travel the upper Midwest, one can still identify many of these former buildings, long ago converted for other uses or even abandoned. Such is the case with this former creamery (pictured above). By road, it was about a mile and a half from the farm where I spent my early years. The buildings were at some point replaced by a concrete block structure and Minnesota State Highway 7 would some decades later be built behind the yellow building, but my earliest recollections of it are as a café/truck stop. It spent several years unoccupied before being demolished in the 1990s for a development. Another creamery building in Watertown, Minnesota added shop space and became an International Harvester farm equipment dealer until the mid-1970s (bottom of this column).

As smaller, local creameries closed, milk had to be transported greater distances than what was feasible by horse and wagon. New positions as milk truck owners and drivers were created and country roads were busy with route trucks hauling cans from farms to creameries. This milk hauler is delivering full cans and picking up empties at a plant in Oran, Iowa.

Can hauling was hard work. Each can would hold 10 gallons when full. So, with the weight of the can, roughly 90 pounds each. With all that exercise, it was no wonder that many milk can haulers were built like gorillas! And the hard work was only a part of it. Imagine, if you will, lifting dripping wet cans out of a water tank where they had been cooling and then having to carry them to the truck with an outside temperature of 20 or 25 degrees below zero! Or, when you would have to drive in heavy snow and then trudge through it with heavy cans.

Once the milk reached the creamery, the driver would unload the cans, often on to a roller conveyor, as you can see in the picture at right.

Each farm was given a three-digit number from the creamery that would be painted on their milk cans. That number would identify one farmer’s cans from others being unloaded and insure that each would get their cans back.

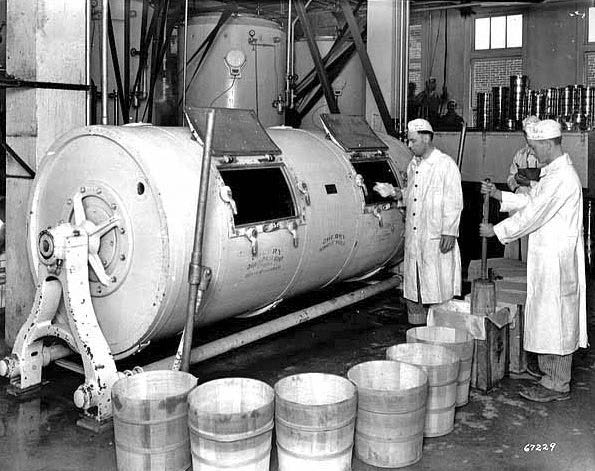

The milk in each can was then emptied, weighed and tested for purity and cleanliness before being mixed with other milk. Testing standards for milk cleanliness and component quantities, such as butterfat content and so on, have become many times more stringent than in the early milk plants.

Many creameries tended to favor production of certain dairy products. Some processed milk as—milk. But most specialized in one, or a few, types of cheese or butter. Even now, if one frequents antique stores and specialty shops, they are bound to come across a new, but unused, one pound butter box with the name of some local creamery, a leftover from when it closed long ago. Those butter boxes are possibly the only trace that remains of some of the old creameries.

As early as 1920, many milk processors sensed that the end of the line was approaching. They were fighting for their corporate lives against what was termed “the centralizer system,” the buyers of cream and makers of butter who had markets that local coops couldn’t reach. It was because of these tough times that Land O’ Lakes was formed in Litchfield, Minnesota. With Land O’ Lakes, new markets for butter quickly opened up and to insure their butter was top quality, milk can coolers were being shipped to farms all around the area. By 1946, Land O’ Lakes boasted 110,000 patron farms shipping milk to them and that they “sell a billion pounds of milk a year!” Land O’ Lakes in Litchfield was termed “District One” at that time. It is now an independent coop branded as First District Association and produces 15 billion pounds of milk per year.

As it was a hundred years ago, some milk is still processed locally in small creameries. Much of that milk becomes cheese. Even with the merging of local plants to large ones, there have always been local milk plants that offer bottled milk and butter and others that produce specialty cheeses, but the numbers of those plants have increased considerably as consumers seek homegrown and organic products.