Before Cyrus Hall McCormick’s death in 1884, he and William Deering spoke of amalgamation, but nothing came of these conversations. Records of the following years indicate that a number of meetings were called to discuss consolidation, but no action was taken.

In late 1890, the American Harvester Company was born. Col. A. L. Conger, president of Whitman, Barnes & Company of Akron, Ohio conceived the idea of consolidating all of the harvester manufacturers into one organization. Conger persuaded each company to set a price on their property, with each receiving shares of American Harvester in exchange. The grand plan of American Harvester Company died in 1891. Bankers turned their back on the idea, and without the necessarily large amount of operating capital, there was nothing to do but resume business as before.

During the next ten years, competition was so keen that only the best-managed companies remained sol vent. Their profits were continually plowed back into bigger factories, modern machinery, and other in vestments, all of which helped them maintain then- status, but left nothing for the stockholders. Mean while, the vast foreign market remained virtually un touched. Every resource and every bit of extra capital was used to maintain a position of rank in the industry. The Harvester War of those years took its toll. Many companies withered in its wake. Those remain ing found themselves in a situation only slightly better than bankrupt.

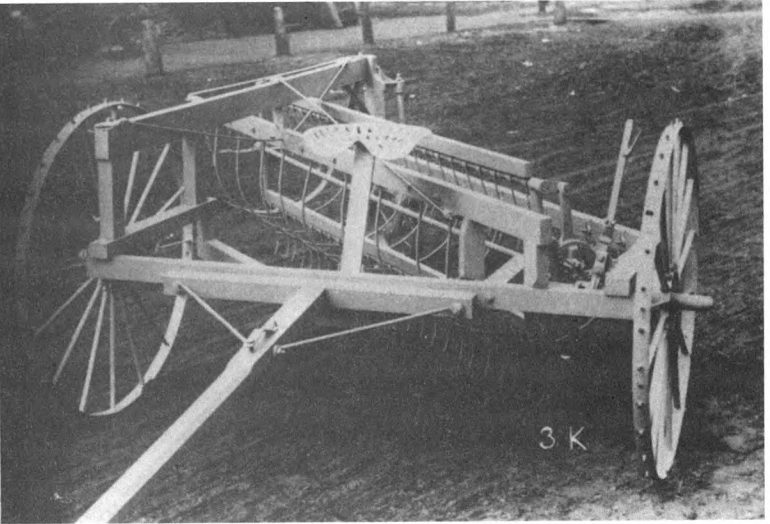

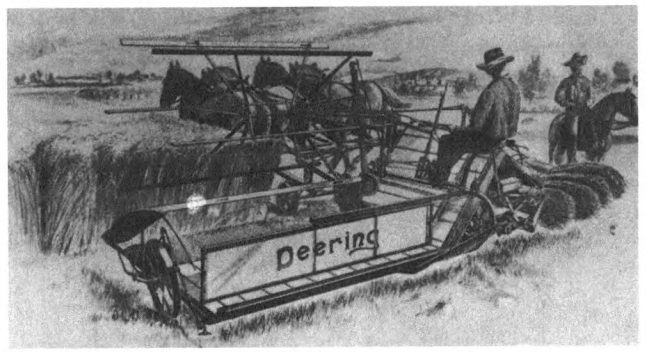

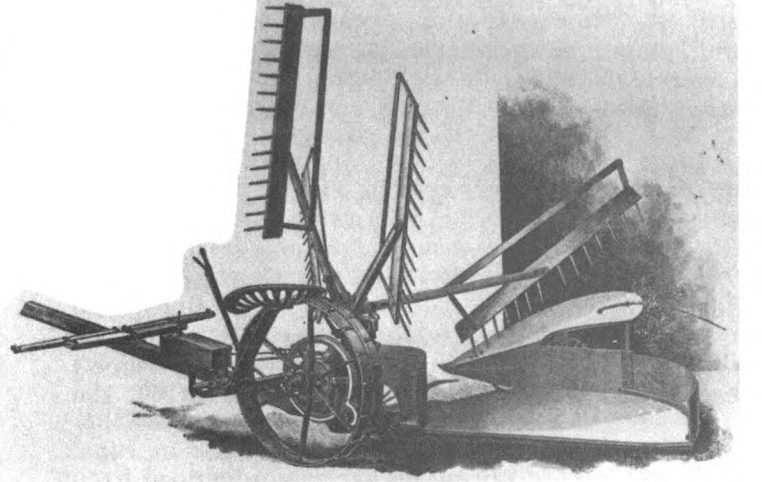

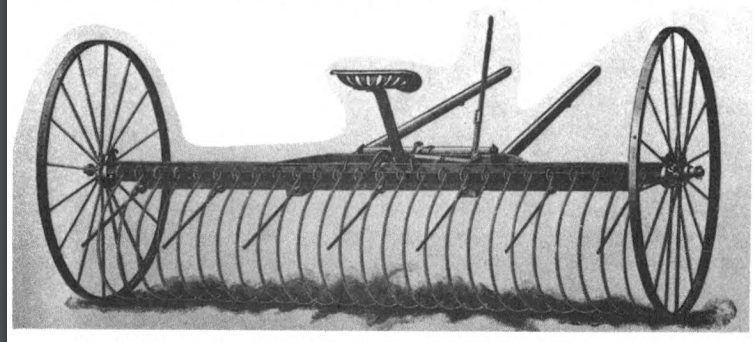

In the five years prior to the International Harvester merger, Deering seemed to anticipate McCormick at every turn. The Deering factories introduced hay rakes, binder twine, and malleable castings before McCormick. To cut costs, Deering acquired vast ore and timber reserves, then went on to build its own blast furnace. Deering could not afford constant expansion, nor could McCormick secure the capital to buy its own steel mill. Although business was still reasonably profitable for both firms, the returns were nowhere in proportion to their growth.

The McCormick people visited New York in June, 1902 with plans of obtaining expansion capital from J. P. Morgan & Company. At this point there seemed to be no other alternative to the Deering challenge. George W. Perkins of the Morgan Company assured the McCormicks that capital could be secured. These conversations led to the subject of merger, with several conferences being held during the next few weeks.

In late July of 1902, the parties to the merger met for the first time at a Morgan conference table. Perkins, a Morgan partner, accomplished in a few weeks time what the reaper kings had never been able to do — he brought them together into a merger. The agreement to form International Harvester Com pany was finalized on August 12,1902. The companies sold their physical assets to the corporation for $60 million dollars. Another $50 million came from bills and accounts receivable, and an additional $10 million was issued to the House of Morgan for cash. Thus the newly formed company had a capital of $120 million.

Stockholders of Plano Manufacturing Company, McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, and the Deering Harvester Company received payment entirely in International Harvester Company stock. The Champion people took cash for their factories, but bought Harvester stock with their receivables. Cham pion at that time was sold by Warder, Bushnell & Glessner Company. Since the owners of Milwaukee Harvester Company had either died or retired, they received cash for their assets, and subscribed to none of the stock.

A voting trust was established for ten years, consisting of Cyrus H. McCormick as President, Charles Deering as Chairman of the Board, and George W. Perkins as the third member. For this ten year period, the voting trust exercised all the normal powers of stockholders. Perkins wisely suggested this course of action, and certainly, the voting trust carried the company through a difficult transition period. Keeping the company out of the reach of speculators by means of the trust, exerted a stabilizing influence during the ten year trust period.

During the first year of operation, the individual sales organizations were left intact, being simply renamed as divisions of International Harvester Company. Old rivals in the field were technically at least, allies overnight. Despite this, rivalry continued to some extent among the partisans, from the top ranks of the company, down to the field agents and salesmen. These were not easy years for the company, but sound management, combined with common sense, put Harvester on a sound financial footing, and permitted new development in foreign trade.

New capital and new resources were combined with fresh enthusiasm for development of foreign markets. By 1906, the trade with Russia alone equalled the en tire export trade prior to the merger. Europe, Russia, the British Empire, South America, and Africa were all buying machines from Harvester. This early development of a virtually untapped market overseas truly made Harvester an “International” company.

Almost immediately after the company was formed, Harvester began building new factories and acquiring old, established firms. A new plant was begun at Hamilton, Ontario in 1903 on land purchased earlier by Deering. The Hamilton plant was to become a major IH operation.

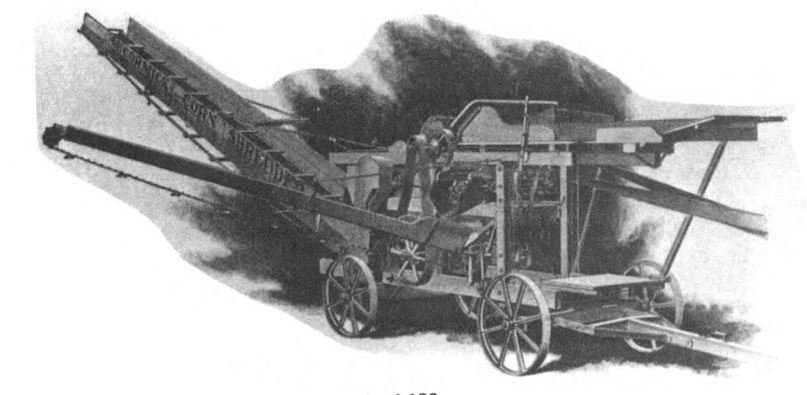

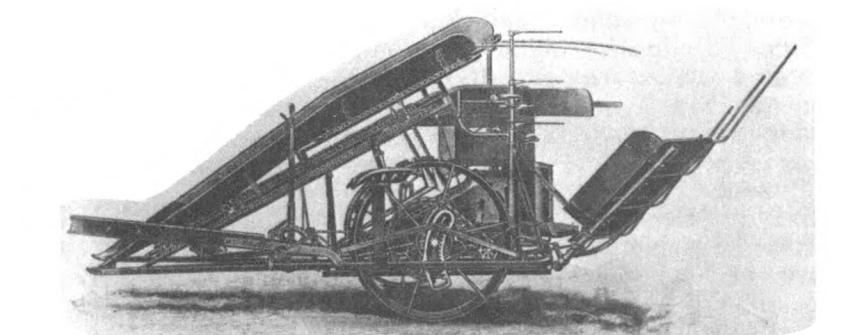

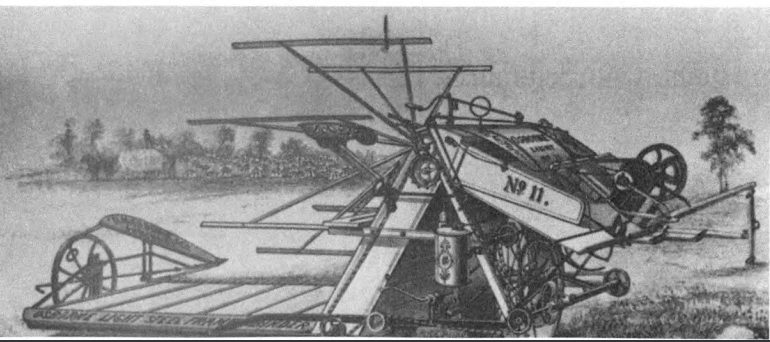

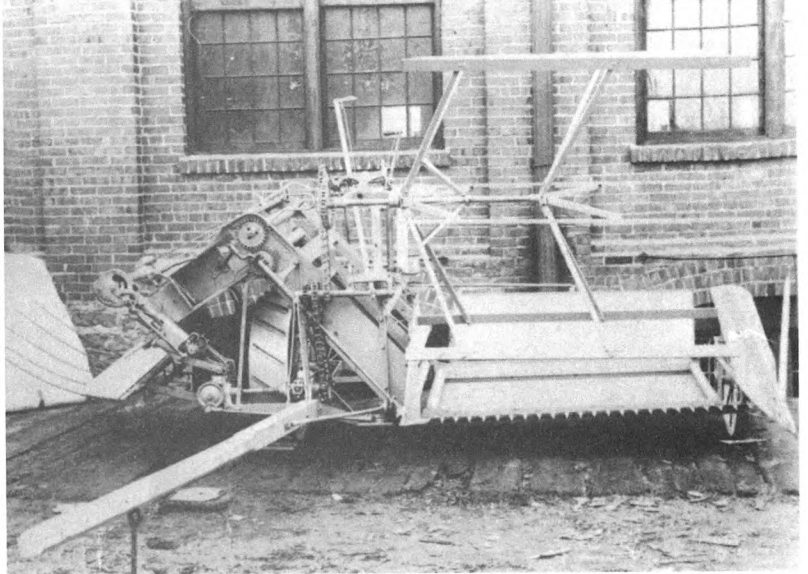

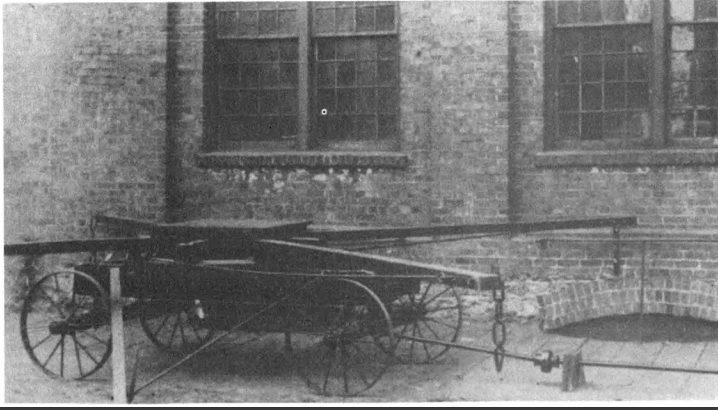

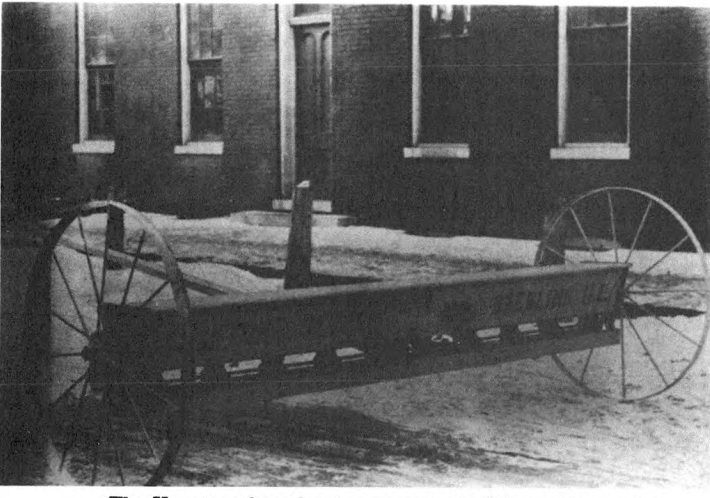

The 1903 purchase of D. M. Osborne Company permitted expansion of the Harvester line on one hand, and eliminated a strong competitor on the other. Osborne and McCormick had been rivals for years, so the blending of Osborne into the Harvester family was a paradox. Aultman-Miller Company of Akron, Ohio was also purchased in 1903, but the acquisition was concealed from the public for several years.

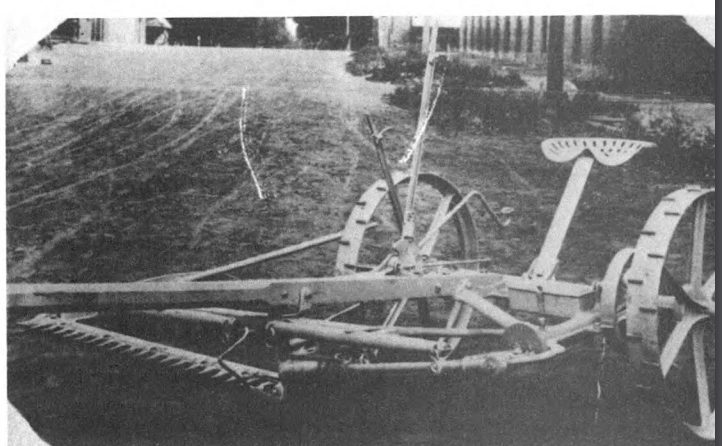

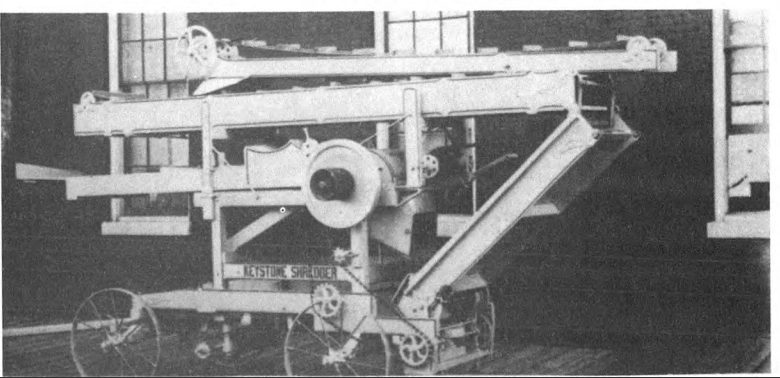

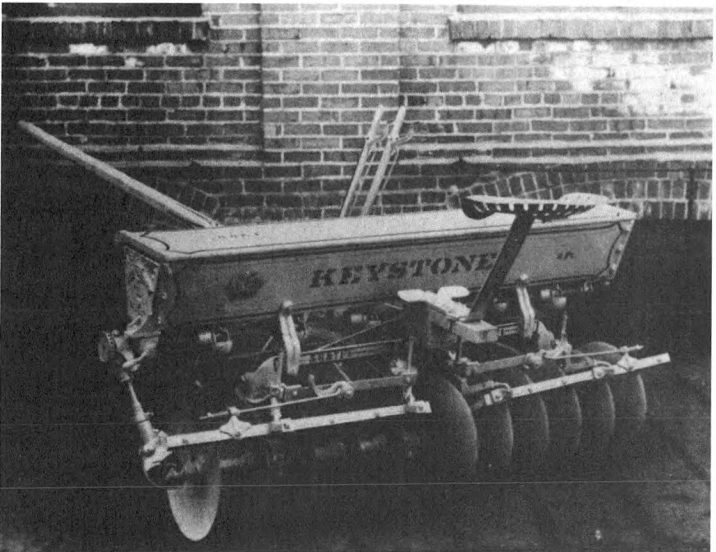

The 1904 purchase of Keystone Company of Rock Falls, Illinois added tillage, haying, and other implements to the Harvester line. The same year, Weber Wagon Works of Chicago was purchased, adding an extensive line of wagons and other vehicles to the inventory.

A losing proposition was the 1904 purchase of the Minnie Harvester Company of Minneapolis. This company had a colorful career, going back some thirty years. Among its ventures, the Minneapolis firm at tempted to make a grass twine. Harvester developed the technical process for making twine from flax straw. Despite the company’s success in making flax twine, the product also turned out to be a five course dinner for grasshoppers. They devoured the flaxen bands without the slightest hesitation. Nothing deter red them from this delicacy. After a loss of over $1 million, Harvester finally conceded to the grasshoppers and abandoned the flax twine business.

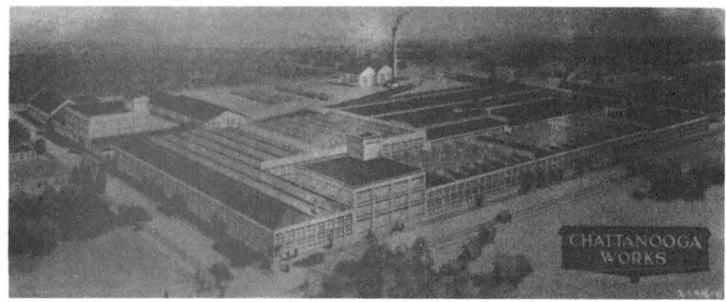

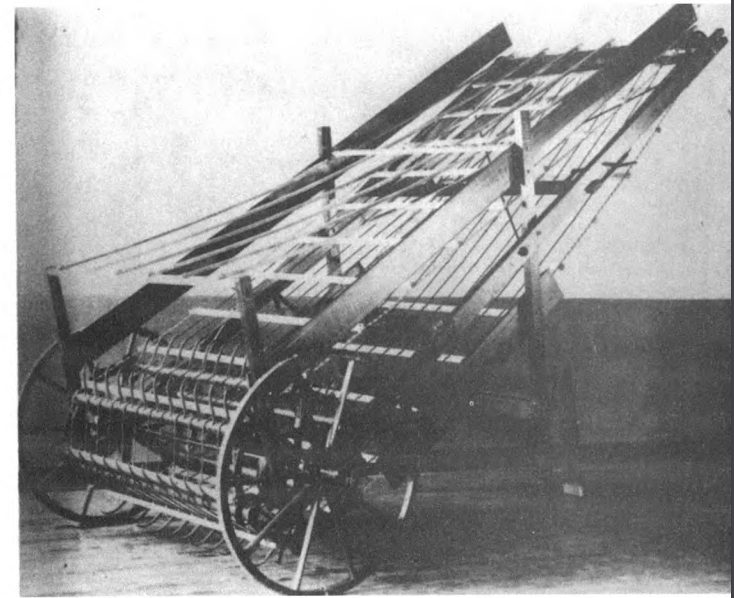

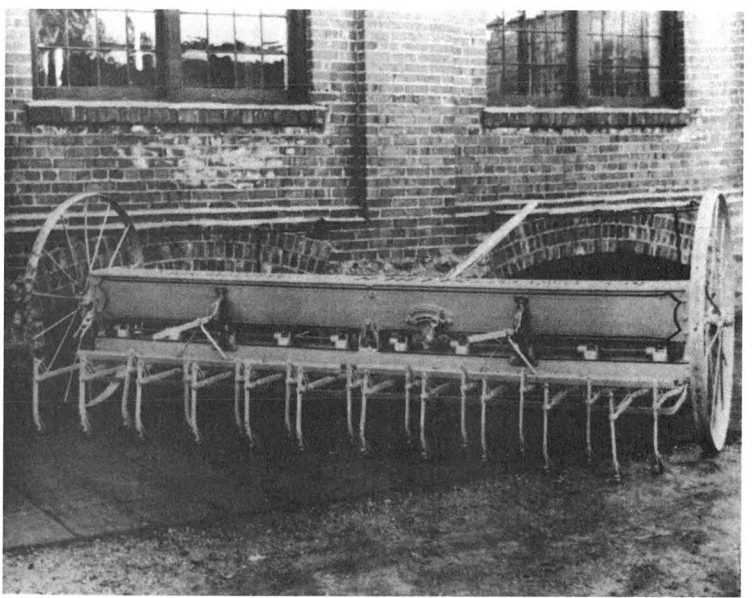

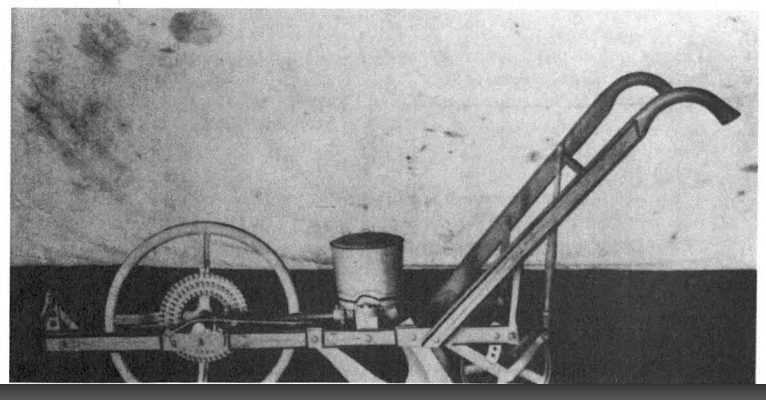

No major acquisitions were made by the company until the 1919 purchase of Parlin & Orendorff Company of Canton, Illinois. P&O had long been identified as a major plow builder, and this addition strengthen ed the IH line of tillage implements. This was bolstered by the concurrent purchase of the Chattanooga Plow Works of Chattanooga, Tenn. Chattanooga was famous for its chilled iron plows, as well as an extensive line of cane presses and related equipment.

The first European plant was established at Norrkopping, Sweden in 1905. A manufacturing site was chosen at Neuss, Germany in 1909, and other plants were established at Croix, France and Lubertzy, Russia.

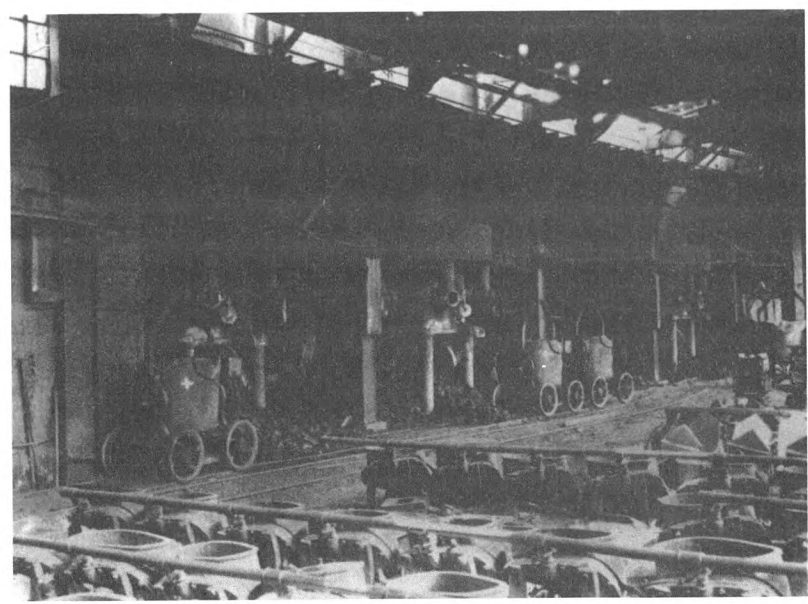

Expansion of the company was by no means limited to buying established companies or building overseas factories. Enlargement of existing plants was a continual order of business. The Deering people brought a stationary gas engine in the merger. Tooling up the Milwaukee Works for large scale engine production was in itself a major undertaking.

Tractor experiments began in 1905 at the Rock Falls Works under the supervision of E. A. Johnston. Through an agreement with Ohio Manufacturing Company of Sandusky, Ohio, the first International tractors appeared in 1906. These tractors used the famous Morton chassis and an International gasoline engine. The first all-International tractors appeared in 1908. By 1910, the Chicago Tractor Works had been completed. In the next few years, the “Titan” and “Mogul” trademarks became household words across America and in the far corners of the world. History was made again in 1924 with the introduction of the “Farmall” row-crop tractor. Since that time, IH has been an industry leader in the tractor business.

Trucks were an early addition to the Harvester line. Beginning with the Auto Buggy in 1907, IH began a career in the truck business that continues at the present time. Rock Falls Works was the site of early truck and auto building, followed by production from the Akron Works. In 1921, truck manufacturing was shifted to the Springfield Works, and in 1923, a totally new plant was completed at Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Although IH construction equipment is discussed only very briefly in this book, it is interesting to note that this separate division evolved from the farm equipment business. As early as 1912, a Titan tractor was designed for conversion into a road roller. Solid rubber tires mounted on a 10-20 McCormick-Deering tractor gave Harvester its first Industrial tractor in 1924. The 15-30 McCormick-Deering was similarly equipped in 1929. A 10-20 tractor was modified with a tracklaying device in 1928, marking the company’s en try into the crawler tractor business.

A Construction Equipment Division was created in 1944. The current Pay Line Division, formed in 1974, covers all phases of the construction, mining, materials handling, and light industrial field.