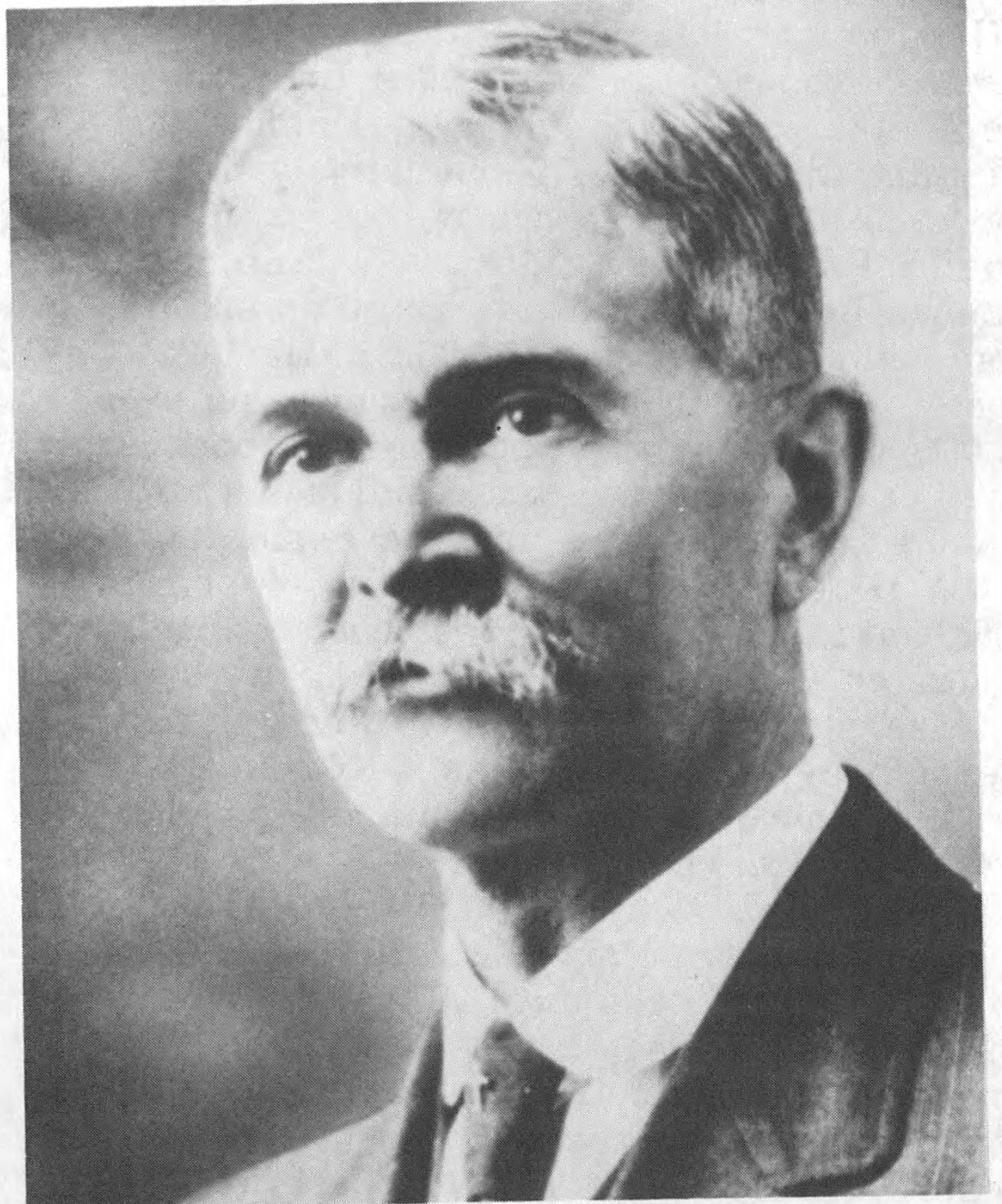

In 1872, Charles Walter Hart was born at Charles City, Iowa. The Hart family had arrived on the Massachusetts shore in 1632…this particular scion of the family came to Iowa in 1871.

After childhood, C. W. Hart taught school for a time, finally enrolling at Iowa State College in Ames for the 1892-93 school year. A year later, Hart transferred to the University of Wisconsin. In September of that year he met Charles H. Parr, and the two young men became fast friends. Eventually, Hart and Parr would work together on their Special Honors thesis…from the designs thus created, the two men created their first engine. The thesis was presented in 1896.

The first section of the Hart and Parr thesis deals extensively with the historical development of internal combustion engines. A second section delves into the atomization and successful burning of various fuels, and using various modifications to the fuel mixing devices. At one point they related, “Our experience has shown that in many cases where electric ignition is used and thought to be faulty, the real fault lies in improper or irregular mixtures.” The thesis later notes, “At first thought it may seem an easy task to construct a mixing device, but when we consider [various problems]…we begin to see the difficulty imposed.” From this section of the thesis it becomes readily apparent that Hart and Parr were wrestling with the problems of atomizing the fuel; a problem that plagued gasoline engine development for many years.

Section 3 of the Hart and Parr thesis deals with ignition systems, and problems with ignition. Considering that ignition systems of 1896 were indeed poorly developed and thoroughly unreliable, Hart and Parr made some interesting observations. Regarding the low-tension, make-and- break ignitor the writers noted, “Our experience has shown that platinum points for the contact pieces within the cylinder are unnecessary. Wrought iron points are just as reliable and require no more current, and with proper combustion of the gases do not become coated.” Hart and Parr go on to point out the continuing cost and the poor reliability of batteries. Then comes the statement, “There is another method of producing the current for ignition which we believe is destined to supersede the battery and which adds complications of a simpler nature only. This is the magneto generator.” Considering the timeframe in which this statement was written, the observation was indeed, profound.

When Hart and Parr wrote their thesis in 1896 they preferred the hit-and-miss method of governing, noting that the throttling governor design had been used only to a limited extent. Their preference was for a system whereby the governor controlled the exhaust valve, holding it open at the top end of the rated speed, and permitting it to operate normally when permitted to do so by the governor. A significant statement appears in this section of the thesis: “We believe that for the best results in governing in this way the valve mechanism should be such that the admission valve be held shut while the exhaust valve is held open.” Numerous companies would later adopt a modification of this concept. In fact, Section 3 of the thesis gives a better idea of their conviction that hit-and-miss governing was preferable to volume governing: “The best and most economical governing is obtained by holding the exhaust valve open and the inlet valve shut. Where very uniform motion is desirable even at the expense of economy, we believe it can be obtained by using a small clearance space or explosion chamber and varying the quantity of the mixture.”

Part 5 of the Hart and Parr thesis involved the valve operating system. For their thesis, the two men developed a 30 horsepower, two-cylinder vertical engine. Their design included mechanically operated intake and exhaust valves; both valves being closed by flat steel springs. The thesis contends that this was an advantage over the usual conical spring, since the entire spring was kept away from the excessive heat of the cylinder head under their plan. For the purposes of this book, it is important to note that using many of the ideas developed at the University of Wisconsin, Hart and Parr appear to have built five engines during 1896.

The Hart-Parr Company was organized at Madison, Wisconsin on April 29,1897. From then until 1901 they operated their engine factory at Madison. During this period they also perfected their valve-in-head engine design, as well as a cooling system employing oil as the cooling medium.

It is unclear whether Hart and Parr had illusions of building gas tractors initially, or whether this idea was developed in the latter part of the Madison years. However, the demand for their engines continued to grow, and larger facilities were needed. Unable to secure expansion capital in the Madison area, Hart and Parr turned to Hart’s father in Charles City. The latter, along with C. D. and A. E. Ellis, persuaded Hart-Parr Company to move to Charles City. Eventually though, the era of good feeling between Ellis and Hart would wane, and Hart would leave the company.

Hart-Parr Company was organized on June 12, 1901 at Charles City, Iowa. Ground was broken for the new factory on July 5 of that year. By the following December the transfer of all machinery and equipment from Madison to Charles City had been completed. Hart-Parr Company was now ready to do business and had an authorized capitalization of $100,000.

Although 1901 is generally credited as the year when Hart-Parr built their first ’gasoline traction engine,’ there are strong indications that it was not actually completed until 1902. In fact, a family photograph of this tractor reads, “First Traction Engine, July 1902.” Another family photo reads, “Second Traction Engine, October 1902.” Then there is the historical information from C. H. Parr, who also indicated that 1902 was correct.

During 1903 the Hart-Parr factory came into full production. Gas engines were still being built, with tractors actually being a secondary product at this time. The following year of 1904, Hart-Parr decided to build “gasoline traction engines” exclusively, and over the next few years the Hart-Parr gasoline engines were gradually phased out.

Also of significance during this period, Hart- Parr placed their first magazine advertisement in the December 1902 issue of American Thresherman. This journal was read by many farmers and virtually every thresherman in the country. It emerged from Madison, Wisconsin every month, under the careful eye of Bascom B. Clarke. When the old-line steam engine builders saw an advertisement for a gasoline traction engine in their favorite magazine, many, if not most of them, nearly had apoplexy. In fact, some threatened to pull all their advertising from Clarke. The latter was well gifted with turning a phrase, and invited them to do just that if they so desired. None did. However, this was the beginning of the end for the steam traction engine. In another two decades the steamer was well on its way to obsolescence, and within three decades, farmers would get their first taste of rowcrop farming with no need of either horses or steam engines.

By 1907 the Hart-Parr Company was well established. Demand for their tractors had grown to the point that by the end of 1908 there were six major branch houses, in addition to the ever-growing factories at Charles City. Part of the factory facilities included a unique engine testing system. At the power house, numerous generators were set in place. As each tractor came off the assembly line it was belted to one of the generators. This provided a load for running in the engine and providing a fill-scale test prior to leaving the factory. The power thus generated was not wasted, but was sent back into the factory as electrical power. Also in 1907, Hart-Parr started the use of the term, ’tractor’ instead of the clumsy term of ’gasoline traction engine.’ Actually, the term ’tractor’ goes back to the time of Shakespeare, but this was apparently its first use in connection with gasoline-powered traction engines.

Hart-Parr Company grew by leaps and bounds, employing some 1,100 people by 1911. To accommodate them, Mr. Hart directed the company to buy farmland on the east side of Charles City. This was then platted for houses to be rented or sold to Hart-Parr employees. C. W. Hart was also very active in civic and community affairs.

With tractor production growing each year, it soon became obvious to Hart that transportation facilities in and out of Charles City were dreadfully inadequate. So, C. W. Hart masterminded the Charles City Western Railroad. It was a 13-mile line running from Charles City to Marble Rock, Iowa. At this point it connected into the Rock Island Railroad. There are indications that Hart built an automobile sometime during the 1906-08 period, as well as an experimental crawler tractor. During World War One, it appears that Hart-Parr Company built, or at least intended to build, motor trucks for the U. S. Military.

By 1915 the Hart-Parr Company was capitalized at $2.5 million. Hart was riding a wave of success, but this was soon to change. The company began retooling for the manufacture of munitions in 1915. Tractor sales were not maintaining the brisk pace of the past, and a disastrous fire struck the factory in 1916. In addition, it is said that Hart-Parr had sold tractors in Europe, and many of these were not paid for. After spending considerable money on tooling up for the British munitions contract, a military change in plans saw an abrupt cancellation of the project. This left Hart-Parr sitting high and dry with a lot of partially completed shell casings. In addition, C. W. Hart had designed special lathes for machining the shell casings; these lathes were designed, cast, and built within the Hart-Parr factories.

Rumors have circulated for decades that another contributing factor was the allegation that the Ellis family, which was heavily invested, quietly picked up all available stock, and eventually took over the managerial control of the company.

It appears that numerous factors were involved, with some probably being more factual than others. Regardless, C. W. Hart left Charles City in 1917. He did not reside there again. From Charles City, Hart and his family headed for Montana, apparently in the spring of 1918. They landed at a town called Hedgesville. In the fall of 1918 the family moved back to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Meanwhile, C. W. Hart remained in Montana, attempting to commute when possible, and dividing his time between his family and the wheat ranch.

Apparently, Hart found time to experiment with a new tractor design during this period. It resulted in a three-cylinder model which eventually bore Patent No. 1,509,293. Two or three of these tractors were built and shipped to Montana, along with a large supply of spare parts. Hart also worked with C. E. Frudden in tractor development. The latter had been Hart’s chief engineer at Charles City, but apparently Frudden left at the same time as Hart, or shortly thereafter. He relocated to the Milwaukee area and was a tractor engineer at Allis-Chalmers for many years. Hart’s involvement with Frudden regarding the development of the early Allis- Chalmers tractors remains unclear. There have been various statements from family members in this connection, but it is our belief that the full details of this arrangement will probably never be known. The important point is that once Hart built the three-cylinder tractors, his career as a tractor builder ended. Hart now concentrated on wheat farming and oil refining in Montana.

In 1919 C. W. Hart applied for Letters Patent on a header barge, although the patent application simply stated, “Method of Harvesting Grain.” On June 19, 1923 Patent No. 1,458.936 was issued to Mr. Hart. Some wheat growing areas used headers…a machine which left as much standing straw as possible, while cutting the stalks just below the grain. The header barge was designed receive the headed grain from the sickle. While traveling through the field, the headed grain tends to settle in the barge, and by the time it is filled, it has become a compact mass. On arriving at a suitable dump site, the header barge simply deposits its load and returns for another.

After the 1920 harvest, C. W. Hart set up a small refinery as a commercial experiment. This would soon become the Hart Refinery. Oil came from Cat Creek Field, Montana’s first commercial oilfield. Ostensibly, Hart set up the refinery to obtain kerosene for use in his tractors. In fact, it appears that the gasoline was sold off to local garages and filling stations. Eventually, Hart had ten filling stations to which he supplied gasoline and other petroleum products.

On the basis of the successful refinery at Hedgesville, Hart and a partner set up a larger refinery at Missoula, Montana in 1924. As with the tractor company, financial troubles again loomed, but Hart remained indomitable. Various family members have described his character, using adjectives ranging from grumpy to reclusive. Perhaps his dislike for bureaucrats illustrates C. W. Hart’s clever mind:

In 1931 the Montana Legislature passed a law stating that gasoline sold in Montana could not contain more than two-tenths of one percent sulphur. Gasoline from the Hart Refinery was above this level, and he had no plans to change his refining methods. After a long war of words, and when it appeared the bureaucrats were about to close in, Hart made a clever move. Virtually overnight, Hart changed all the signs and all the advertising to read, “Hart Auto Fuel.” This of course, was no longer gasoline, but auto fuel, and there was nothing in the law to cover it. So the bureaucrats took their lumps and Hart went on with business as usual.

As with the tractor company, the first few years of the Hart Refinery were profitable. As with the tractor company, a major fire in the Hart Refinery was a precursor to financial difficulties. After the disastrous refinery fire in 1929, plus the Great Depression which struck at the same time, Hart Refinery went into debt. Yet, C. W. Hart remained indomitable. During 1935 and 1936 he signed a contract for construction of a refinery near Cody, Wyoming. This particular field had been discovered in 1931, but the major refiners were not interested in the crude because of its low grade. However, Hart designed a cracking still, refinery, and auxiliaries to successfully refine the low-grade crude. This was the last major project for C. W. Hart.

On Sunday, March 14, 1937 C. W. Hart died from a heart attack at the age of 65. His remains were returned to Charles City, Iowa with his old partner, Charles Henry Parr delivering a burial dedication for his longtime friend.

Thus ended the career of a most interesting and innovative personality. Various writers have pointed to the man’s qualities and to his faults. There is no question that Charles W. Hart was one of those farsighted men who made ’tractor power’ a reality. There is no question of his inventive genius, and there is no question of his business acumen. Yet, it is equally obvious that C. W. Hart was plagued with a heaping measure of life’s adversities. In fact, his entire career is checkered with numerous high points, and other times which epitomized hardship and trouble. It has been said that Hart was essentially goodhearted, but that some of the various reverses in his life caused him to be bitter and harsh in his later years. Yet, for the purposes of this study, it is perhaps best that those purely personal aspects of Mr. Hart’s life be left at rest. Perhaps it is better that this study should concentrate instead on Mr. Hart’s technological developments, especially regarding the development of the farm tractor.

Charles Henry Parr

While considerable research has been conducted regarding Charles W. Hart, relatively little history had come to light in connection with Charles H. Parr. As indicated in the previous section on Mr. Hart, the two young men met at the University of Wisconsin. From all appearances, Hart was the quintessential extrovert, bold in actions, and possessing a keen mind. Parr on the other hand, appears to have been a comparatively reserved personality. Various writers have concluded that it was Hart who came up with the ideas, and it was Parr who was able to make the drawings and reduce ideas into practical terms.

During the time that Hart and Parr worked together (into 1917) there are indications that Hart worked in the daytime, while Parr was the night superintendent. Yet, when Hart left the company, Parr remained, apparently content to maintain status quo, rather than strike out on his own. Despite their different personalities, Hart and Parr remained friends, even though their paths took distinctly different directions.

In 1918, and apparently after Hart had left the tractor company, C. H. Parr wrote up a history of Hart-Parr Company. Parr noted that they began business as Hart & Parr, Madison, Wisconsin. By that time they had several engine designs and several sets of foundry patterns. Yet, investment capital was very difficult to obtain, and the two partners were forced to operated under the most meager circumstances.

Although the business was organized in 1896 as Hart & Parr, it was reorganized as Hart-Parr Company on April 29, 1897. This company had an authorized capitalization of $24,000. The first annual stockholders meeting of January 4, 1898 showed an operating loss of $354. The following year of 1899 indicated an operating loss of $491, but in 1900 there was a profit of $454. In January 1901 the company had a profit of $1,564.

By now it was obvious that the company needed growth capital. Yet, no serious investors could be found. In the early part of 1901, C. W. Hart was visiting his family at Charles City, and related his problems to his father. The elder Hart discussed the matter with some of the bankers and businessmen in Charles City. Thus, on May 14, 1901 the Hart-Parr Company at Madison, Wisconsin voted to accept a proposition to move to Charles City. On June 12,1901 the Hart-Parr Company was organized at this place with an authorized capital of $100,000. Among the original investors were C. D. Ellis and A. E. Ellis, two brothers who were bankers in Charles City.

Parr’s history of the company also relates that the Hart-Parr gasoline engines were especially intended for the large grain elevators. From Parr’s history, and from other sources, it appears that the company did indeed ship many of its gasoline engines to the western prairie states for use in grain elevators. Parr also relates that the first tractor was sold to a farmer near Mason City, Iowa. The first owner used the tractor for several years, and then it was sold to a neighbor who continued to use it for threshing. As late as 1917, the engine was still operating, but by now the chassis had been scrapped, with the engine operating a factory and repair shop.

Other typewritten notes indicate that when Hart left the company in 1917, [Parr] was “not in a position to leave at once, [and] accepted a position in the Engineering Department under the new management, which he held till November 1923.” Other file notes indicate that during this time Parr designed special tools and foundry equipment for use in the production of war materials. From November 1923 to July 1924 Parr was Chief Engineer for the Elgin Street Sweeper Company of Elgin, Illinois. Apparently, Parr then returned to the Engineering Department of Hart-Parr Company. When the later merged with other companies in 1929 to form Oliver Farm Equipment Company, Mr. Parr remained with the new firm. Charles Henry Parr died in 1941, and is buried in Charles City, a short distance from his associate, Charles Walter Hart.

Hart-Parr Company

While the previous paragraphs have provided a cameo view of Hart and Parr, this section deals with the Hart-Parr Company from its meager beginnings, and continuing up to its merger into Oliver Farm Equipment Company in 1929. Since the principals, Hart and Parr, are inextricably entwined, a certain amount of redundance is present. However, it has been virtually impossible to separate these two men, even from a biographical viewpoint, from the company which they founded.

As previously indicated, the firm of Hart & Parr officially began building gasoline engines at Madison, Wisconsin in 1896. At what point these two men first planned on a gasoline traction engine is unknown. However, given Hart’s creative mind and his indomitable disposition, this may have been in the plans from the very beginning. Yet, the partners remained in the gasoline engine business at Madison until 1901. Conjecture has it that they had plans for building a traction engine prior to leaving Madison, and some rumors exist to the effect that they actually did build some type of tractor there.

It has been often related in the tractor industry that being unable to secure growth capital for their enterprise, Hart and Parr moved to Hart’s boyhood home of Charles City, Iowa where liberal capital was available. During the years at Madison, Hart and Parr had perfected their original valve-in-head engine design, and indeed, by 1900 they were building engines that used an oil coolant rather than water. The higher coolant and cylinder temperatures were conducive to the use of low-grade fuel. Another major advantage was that freezing weather had no effect on the coolant. At the time, the only available antifreeze solutions were calcium chloride and a mixture of water and alcohol. The latter began evaporating at something like 160 degrees F., and so constant replacement was necessary. Calcium chloride is very destructive of iron, so it too, was not very desirable.

Although the industry usually indicates 1901 as the beginning of the Hart-Parr gasoline traction engine, ample evidence indicates that the first tractor was not completed until the summer of 1902. Yet, the company’s official production records show that No. 1205, Tractor No. 1, was built in 1901. If so, could it have been partially built at Madison? It is unlikely that precise answers will be found. More importantly, this tractor was the first of many which ultimately would revolutionize farming methods, and which eventually helped to relegate the steam traction engine to an abandoned comer of the barnyard. This first tractor carried a two-cylinder horizontal engine with a 9 x 13 inch bore and stroke. The huge flywheel weighed 1,000 pounds.

Tractor No. 2 emerged late in 1902, and embodied numerous changes over the first model. With No. 2 (Serial No. 1206) came the first use of the induced draft cooling system which characterized the Hart-Parr tractors for some years to come. Like No. 1, it also used an oil coolant. Hart and Parr were as yet convinced that hit-and-miss governing was more desirable than volume governing. This system was mechanically complicated, but very simple electrically. Educated engineers of 1900 knew relatively little about electrical systems, whereas the mechanical parts were much easier to master.

The No. 3 tractor evidenced numerous refinements. Introduced in 1903, it set the pattern for Hart-Parr tractor design…a pattern which remained fertile for several years. This model carried a two-cylinder horizontal engine having a 10 x 13 inch bore and stroke. Make-and-break ignition was used. Tractor No. 3 was rated at 18 drawbar and 30 belt horsepower. During 1903 Hart-Parr sold fifteen of these 18-30 tractors… operating weight for this monster was nearly 15,000 pounds.

During 1903 Hart-Parr introduced the 22-45 model. It was an improved version of the No. 2 tractor of 1902. The 22-45 was the first standardized model in the Hart-Parr line. Earlier models were essentially hand-built from beginning to end, and it would not be totally unfair to state that those models prior to the 22-45 were in essence, prototype models. In 1904 Hart-Parr introduced a new kerosene carburetor. C. W. Hart also received Patent No. 774,752 covering a “Cylinder Cooling System.” Curiously, the patent drawings illustrate the inverted vertical stationary engine combined with the induced draft radiator as used on the tractors. In 1904 Hart-Parr also introduced magneto ignition for their tractors, apparently using a low-tension ignition dynamo. The following year of 1905 saw the introduction of the force-feed lubricator for precise and reliable oiling of essential engine components. Hart-Parr would continue this lubrication system until the advent of unit frame designs in the late 1920s.

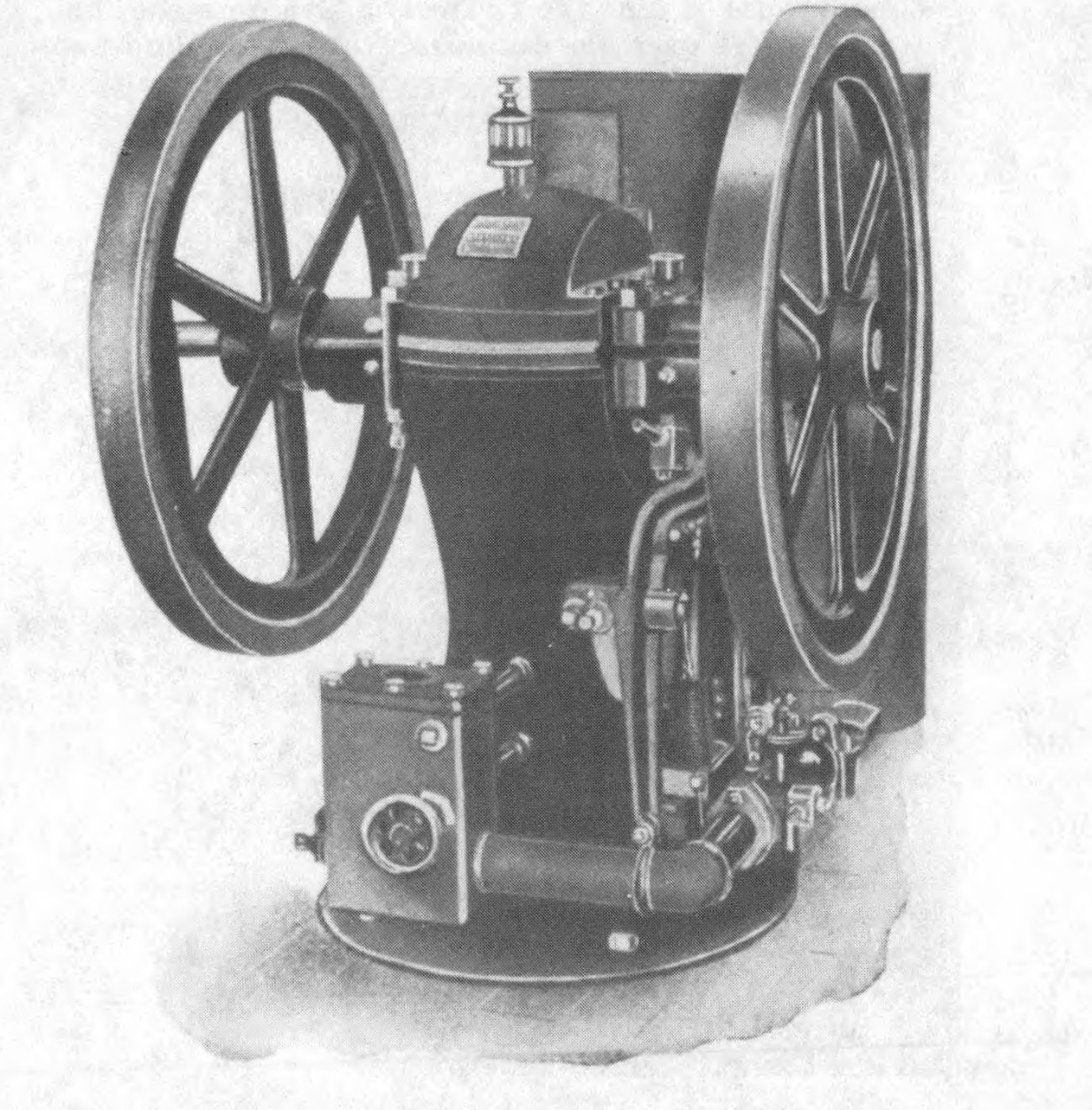

During these formative years at Charles City, Hart-Parr continued building gasoline engines. From all appearances, production of the stationary engines came to about 1,300 units by 1904. Other indications show that engine production was gradually phased out after this time, finally ending altogether in 1908.

Through the years, vintage tractor enthusiasts and historians have commented regarding the design similarities of the Hart-Parr with the somewhat later Rumely OilPull. Indeed, there are similarities. One was that both used an oil coolant. The most obvious is the similarity of the cooling system. Both used an open radiator design. Above the radiator tubes or section plates, the engine exhaust was directed into vertical nozzles. The high velocity of the exhaust gases passing upward through the open stack created an induced draft beneath, and this pulled cool air over the radiator. Since the volume and velocity of the exhaust gases moving up the stack varied proportionally to the engine speed and the load, the cooling system was virtually automatic. It is significant that several other companies also made use of an induced draft cooling system, including the early Avery tractors. A major difference between the Hart-Parr and the OilPull was that the latter used volume governing by interposing a slide (and later a butterfly) in the air intake stream. Hart-Parr on the other hand, continued to use hit-and-miss governing for several years. Some years ago the Author was told that Hart-Parr actually cast and machined the major engine components for the OilPull prototypes. While this is entirely possible, our research has found nothing to either confirm or deny the story.

Between 1907 and 1918 Hart-Parr produced what was to be one of their most popular tractors for the period…the invincible “Old Reliable” 30- 60 model. Top speed was 300 rpm. However, at this speed there were two pistons of 10-inch diameter traveling within cylinders having a 15- inch stroke. In fact, Hart-Parr built 205 copies of the 30-60 in 1907. By comparison, less than 400 tractors had been built in the period from 1901 through 1906. Over 200 of the 30-60 tractors emerged in 1908…there was now no doubt whatever that Old Reliable was on its way to the history books!

As has been indicated earlier in this section, Hart-Parr experienced growing pains almost immediately after setting up shop in Charles City. Plant expansion was the ruH rather than the exception, and by 1908 the company had established six major branch houses in addition to the Charles City factory. Also in 1908 the company began its first major exports to foreign countries.

In 1907 Hart-Parr first began applying the use of ’tractor’ to what had formerly been ’gasoline traction engines.’ Initially, it was probably an advertising gimmick, but the new designation was much more simple than the old one, and it stuck. Before long, ’tractor’ was a household term. Also of significance is the fact that when Hart and Parr set up their Charles City factory, it was the first one in history to be designed for the exclusive production of tractors. Thus, Hart and Parr deserve recognition as truly being the founders of the farm tractor industry.

The great success of the 30-60 model prompted Hart-Parr to develop an even larger tractor…their 40-80. Built in the 1908-1914 period, this huge four-cylinder tractor weighed some eighteen tons! Oil cooling was used, along with high tension ignition and a magneto. As was typical of Hart-Parr tractors, this one also used a force-feed lubricator, with oil making one trip through the engine. Although wasteful of oil, compared to present standards, it must also be remembered that this system helped keep the engine clean, thus prolonging its life. Efficient oil filter systems simply were not the reality in tractors of this period.

Recognizing the need for a smaller tractor as well, Hart-Parr then introduced the 15-30 model in 1909. Built until 1912, its original design used an engine with two opposed cylinders of 8-inch bore and 9-inch stroke. This was later replaced with a vertical engine design. This was also the first Hart-Parr tractor to be furnished with two forward speeds.

Huge steam traction engines and huge tractors were sensations of the early 1900s. Like some of the other companies, Hart-Parr also built a colossal giant, the huge 60-100. Relatively little is known of this tractor, even by those who have studied the company extensively. The serial number lists tend to indicate that a dozen or so were built. However, the 60-100 was the largest tractor of its time…it weighed something over 52,000 pounds. Where they were shipped or whether they were at all successful is unknown. Rumors have abounded that the remains of a 60-100 rested, or perhaps still rest, in a Montana scrap yard, but the rumor has never been substantiated. Only during 1911 and 1912 were any of these gigantic tractors built. After that time the company followed the demands of farmers for a small, lightweight tractor suitable for their average quarter-section spread.

Tractor production continued apace with the introduction of the Hart-Parr 20-40 in 1912…it remained in the lineup until 1914. Again, a twocylinder vertical engine was used, along with force-feed lubrication and a K-W magneto. An overlapping design was the Hart-Parr 12-27 model which emerged in the 1914-15 period. This smaller, one-cylinder tractor was oil cooled, used jump spark ignition, but had no magneto. The engine carried a 10-inch bore and stroke.

In 1913 and 1914 the Bull tractor came on the scene. Despite its faults, and despite the simple fact that the Bull was essentially a poor design, it was nevertheless a small, lightweight tractor that farmers would buy. Between its obvious usefulness, its low price, and an eminently successful advertising campaign, Bull tractors hit the industry like a firestorm. Eventually, many of the competitors either capitulated to lightweight designs or left the market altogether. Hart-Parr chose to respond with their ’Little Red Devil.’ It was altogether unlike anything that Hart-Parr had ever built. In fact, given C. W. Hart’s business acumen, it seems entirely possible that he acceded to the Little Red Devil purely from a business standpoint, rather than looking at it as the epitome of tractor design.

Rated at 15 drawbar and 22 belt horsepower, the Little Red Devil was powered by a two-cylinder, two-cycle engine. The single rear wheel obviated the need for a differential. Since the two-cycle engine was reversible, there was no need for a transmission, and of course this engine style had no valve mechanism. Production of this tractor began in 1914 and ended in 1916.

The Hart-Parr Oil King 18-35 model first appeared in 1915, with production, ending in 1918. Its one-cylinder vertical engine retained the oil cooling system and the induced draft radiator. Apparently, a substantial number of these tractors were exported. In 1919 the Hart-Parr 35 Road King tractor appeared as an improved version of the 18-35 Oil King. Production began and ended that same year, and this marked the end of the Hart-Parr heavyweight tractor designs.

As noted in the biographical sketch of C. W. Hart, the company became involved in military ordnance production for Great Britain during World War One. This required a considerable investment in new equipment, and due to the scarcity of specialized machinery, Hart-Parr designed and built much of it at the Charles City factories. During this time however, C. W. Hart was busy at an entirely new tractor design…in fact, when he abruptly left the company in 1917, the new tractor hadn’t even been built yet. In fact, after 1917 the Hart-Parr Company and C. W. Hart had but one thing in common, and that was the use of his name on the billhead! His final legacy to the company was the New Hart-Parr 12-25 which emerged in 1918.

With the coming of the New Hart-Parr 12-25 the company once again changed the face of the tractor industry. In this same connection though, tractor collectors often comment about the similarities between the New Hart-Parr and the concurrently built Waterloo Boy tractors. To be sure, there are similarities, but whether by accident or whether by design, no information has ever surfaced to precisely indicate how Hart-Parr developed their concept of the ideal small tractor. Similarities aside, the New Hart Parr and its siblings immediately became very popular with farmers.

Right on the heels of the New Hart Parr 12-25 came the Hart-Parr 15-30 “A” tractor. This model was built in the 1918-22 period. When the Nebraska Tractor Tests began in 1920, the Hart- Parr “30” as it was known, made its debut in June of that year. It yielded an impressive fuel economy of 8.04 horsepower hours per gallon of kerosene. Subsequently, Hart-Parr introduced their “20” tractor in 1921, continuing it until 1924. Also in 1921, Hart-Parr introduced stationary engines, using the comparable tractor engines, but mounting them on a substantial cast iron base. This continued until at least 1929. Numerous improvements and new models appeared during the 1920s. Yet, the days of the Hart-Parr were numbered…farmers wanted row-crop tractors.

An interesting diversion of the 1924-27 period was the Hart-Parr washing machine. Apparently the company decided to cash in on what was then a booming market, and in fact, it appears that this machine was innovative and fairly popular. Despite all the positives, sales were apparently not so great…if they had been, the Hart-Parr washing machine probably would have been on the market for more than three years.

With the Hart-Parr 28-50 of 1927-30 the era of C. W. Hart’s tractor designs was ending. The company was in serious financial problems, so serious in fact, that a merger seemed the only sensible thing to do. Thus, on April 1,1929 Hart- Parr Tractor Company merged with Oliver Chilled Plow Works, Nichols & Shepard, and American Seeding Machine Company to form the Oliver Farm Equipment Company. The following year came the Oliver-Hart-Parr 18-28 tractor, an entirely new model with a unit frame design and a vertical engine. In the 1935-37 period the Hart- Parr name was dropped, and from that time onward the tractors came out under the Oliver banner. It is indeed ironic that the Hart-Parr name was dropped about the same time as C.W. Hart departed this earth in 1937. Four years later, in 1941, Charles Henry Parr would be buried in the same Charles City cemetery where he had earlier delivered a graveside eulogy for his lifelong friend, Charles Walter Hart.