Prologue

My first real tractor ride was in summer 1950.

I was almost four years old. Dad was breaking stubble on my grandad’s place in July. He sewed a five-bushel burlap oat bag after filling it with straw from the straw pile.

The tractor was a 1927 “D” John Deere with steel rear wheels and rub-ber tires improvised on the front—rims welded to the spokes. The sack of straw sat on the gear case and I sat on the straw. The fender braces made good hand-holds when needed.

Looking back, I loved to watch the four discs slice their nine-inch strip of “stubble,” blackland-prairie rich with residue of oat stems, green with grazed over clover sown with the oat crop, the fragrance of teaweed and a bit of Johnson grass. Burnt kerosene and teaweed are a perfume never forgotten.

Although hot and dry, the soil is not terribly hard. The steel cleats penetrate to the rims and the ride is tolerable for Dad and fun for me. Each disc throws its sod about three feet into the air and it falls to earth and crumbles into small chunks of black clods fuzzy with tap roots of life-giving clover residue. I became addicted to farming, riding the old “D” racing along in high gear with the “four blade disc.”

Of threshers and lonely combines

This story contains my memory of grain harvests from 1952 into the early 2000s on my family’s dairy farm on the blackland prairie of Texas. My dad and his two brothers built an 11-cow “flat” grade A dairy barn in the year of my birth, 1946, and chose to grow their own feed for the Jersey herd on the 320-acre farm by raising about 100 acres of oats, 40 acres of silage and about 60 acres of wheat as a cash crop at harvest, but a valuable grazing crop. The small grains were usually grown with yellow blossom sweet clover—biannual for additional graz-ing hay and soil fertility. One hundred sixty acres were permanent pastures—creek-bottom land with excellent fishing, hunting, and picnicking—manicured to park land by the productive Jersey herd.

The brothers tried king cotton, prevalent in the blackland, for a few years, but even grade B dairying was a four season income and grade A with surge milk-ers, International Harvester can coolers, no separator and concrete floors was much better.

In 1952, the last year of harvesting grain on our farm by the thresher, the oats and wheat were cut with an eight-foot McCormick-Deering binder and shocked by family labor and one or two hired men.

By then, I had learned to carry at least four bundles at a time (being large for my age). The bundles were put in rows eight feet apart, about 12 in a pile as dropped by the man riding the binder whose foot controlled the carrier by means of a pedal. My grandad was an expert at tying the bundles at the proper point so they balanced perfectly. He had two Deering binders powered by Percherons (Big Boy and Shorty) when he stopped farming, but rode binders for my dad into his 80s.

Bundled and shocked, the grain was secure for about three weeks or more. Cut mature and a bit green and standing tall, it needed time to ripen and dry, storms rarely hurt its quality and threshing usually was done in mid to late June.

Our thresher was a Minneapolis machine with a 28-inch cylinder, Garden City feeder, solid rack with windstacker probably built in the teens. It had been checked thoroughly, greased, tightened during the previous weeks and sat in a spot where we wanted the straw pile with its iron rear wheels dug in about 10 inches to facilitate straw flow. The bundle wagons, five or six, were made ready with nails and baling wire, an old model “A” truck was pulled off to start, tuned up for use as a bundle hauler, granaries were cleaned and the elevator built by Little Giant was set in place. The 1928 “D” JD got a change of fresh 40-weight Co-Op heavy duty oil and we could then begin to work.

The “thresher ring” of my grandad’s day was gone—neighbors pooling resources to buy a thresher and furnishing family labor to thresh all their grain. At the end of the thresher-era, we hired our help. Mom called the crew on the party line telephone.

Fortunately, help was still abundant— semi-retired farmers, high school farm boys keen to earn a day’s pay with a pitchfork, most any rural person whose crop was laid by could spare a few days to earn an honest wage. Several people brought their own tractors to pull our formerly horse-drawn bundle wagons.

The first day, and for the next eight to 10 days, I rode with my mom to pick up about four men who had no transportation but were eager to help and enjoy associating and participating in good company. Shortly after daylight, we arrived at the farm where milking was being finished a bit early. Strange tractors came up the road—F-12s, VACs, “B” Farmalls and my grandad with his 9N; three or four school boys in a jalopy to load the wagons but not to pitch into the thresher—some of the older guys would do that somewhat dangerous work.

In short order, wagons were hooked up, loading begun, the 1936 Ford grain truck with Galion hydraulic lift (our most modern convenience) was parked under the measure spout— harvest began as soon as the belted and set JD “D” was warmed up.

Now came my small part of the production. It was now about 8 a.m and time to prepare dinner (and I will not call it “lunch”) for about 12 men and family (uncles and Grandad). My cousin, 12 years my elder, and I had a part, which was to gather the food. We had a large garden and it was in full production. Our orders were: a bushel of Irish potatoes, one half gallon of radishes, 30 onions, lots of Simpson leaf lettuce, 20 cantalopes, 50 ears of corn, two bushels of black-eyed peas, two gallons of okra and lots of tomatoes. From the orchard: four gallons of plums—Ozark Premier, early peaches for fresh cobblers, then we went to the cellar and got last year’s peach pickles and beet pickles, jars of last year’s honey, pinto and green beans, grape juice, canned apples for cobblers and pear preserves.

While we were busy at this assignment, which was easier than it may sound because of its abundance, our moms were preparing dishes, pots and pans, and heating water. We were very soon arriving with the potatoes, which rolled out of the dry black soil almost as clean and white as tree fruit, and in sizes ranging from golf ball to softball size, filling a one-half bushel in no time.

This was at the end of the smokehouse era, but ours was still used in 1952 and Mom made good use of it this year. She prepared the main course of hams and shoulders, ribs and bacon from our own home killed hogs. We also had two International Harvester deep freezers full of roasts, steaks and briskets at the start of the 1952 threshing. These were the main courses for our meals. The only thing lacking on the food part of threshing was the kitchen comraderie my mom spoke of when the threshing ring prevailed—the wives met at the farm where the the thresher was and prepared the meal together and thus enjoyed each other’s company while doing their part in the harvest.

At high noon, all work stopped, the men assembled at one of our farmhouses (our farmhouse or my uncle’s), washed up outdoors at a shaded faucet (soap and towels provided) and came in to tables and chairs in the kitchen, dining room, porches, even bedrooms. Thanks were offered, dinner served by my mother, aunts, cousin and me. This was threshing ring tradition and apparently no one thought of changing it in our part of the world; about 10 or 12 men partook of ham, roast, steak, garden salad, potatoes mashed, grated, potato salad with boiled eggs, deviled eggs, peas, beans, corn on the cob cut from the cob and fried. My job was to bring more dishes as required, deliver iced water, tea and coffee and dessert—peach and plum cobbler, peach pickles, beets, grape jelly (we had about 40 grapevines), jam and marmalade. Many of the men requested the real thresherman’s dessert—a plate of molasses (we kept more than one kind)—which they mixed with fresh Jersey butter and ate with freshly baked yeast bread.

All this food was either freshly gathered or preserved and kept in the cellar, smokehouse or freezer. The only purchased items were mayonaise, mustard, catsup, ice, coffee, tea—strangely no soft drinks or alcohol even mentioned. The men thanked us—my mother, aunts and cousin—for the meal and got back to work.

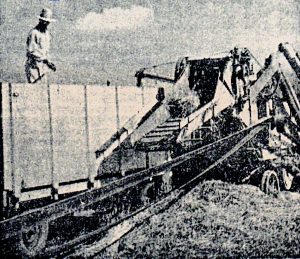

After the dishes were washed and dried, I was free to go to the thresher and try to stay out of the way. I had been straightly warned of the danger of belts, pulleys, moving tractors, dropped bundles, pitch forks and other hazards. I knew oat dust was very itchy. At age four, I tried to scratch the itch away and my uncles laughed ’til their sides hurt. The men in the field loaded the iron-wheeled wagons by pitchfork, pitching the shock—40 to 50 bundles set up like a teepee and thatched to shed rainwater— into the wagons, which held maybe 2,000 bundles. The wagon (or model “A” truck) was driven or pulled beside the feeder and the driver—or if the driver was too young or old, another man climbed upon the load, started putting one bundle after another, head-first, beside the divider board on his side of the feeder. The conveyer carried the bundle into the feeder, which cut the twine, spread the bundle evenly and the spike-tooth cylinder threshed the grain from the straw. The grain fell onto the sieve (or raddles) set to let oats be parted from the chaff which was blown over and away; the heavier grain fell through the wind blast from the fan into the clean grain floor, augered and elevated to the measure, which dumped and counted every half bushel into an auger to the truck. The straw and chaff were in “modern” threshers, blown onto the strawpile by the wind stacker.

In earlier times, grain was bagged, sewn by needle and thread, stacked or loaded by hand. Grain handled in bulk would save at least four jobs.

This 28-inch cylindered machine could handle two good pitchers at once, though the “D” JD worked at full load and was very loud. I tried to pitch when my dad worked a load and found it to be difficult. Skill was required to find the next bundle, spear it, turn it head first pitch or flip it onto the conveyer without losing balance and falling. The next one was waiting, laughing at you—here I am, uncovered, can’t you see me? Stop and look, find one not covered, by parts of other parts of bundles, stab it so it doesn’t roll and pitch it. Experienced pitchers could make it look so easy, but they couldn’t teach it. At least that’s my take on pitching bundles. Horse-drawn hay frame drivers stacked their loads, which may have made it easy to unload. Our men could lay bundles head to butt all day, like chopping wood or milking cows. It seems an art lasts until it is no longer needed.

Two men were delegated to haul grain to the barn, unload and return for another load. One drove the Ford, the other a “B” JD and grain trailer.

One or two men in their 60s helped where needed: pitching off a load, greasing, keeping ice water handy. My dad supervised the thresher, trying to eliminate choke ups or break downs. The handheld tachometer told him how the tractor machine was precisely doing—humming and straw swishing down the long stack pipe.

The straw pile grew and grew. After about three days, the wind stacker could no longer blow straw over the top—straw fell back onto the machine, hooked up, circled to a spot calculated to continue the pile. Rear wheels dropped into new holes, belt lined up (another art) in about a half hour, then back to work. (A wind shift could cause a machine move if the long drive belt was affected.)

The straw pile was very useful. Cows would eat the straw in winter. As big as a huge barn, they would eat out a cavern 20 feet into the south side of the pile, which was softer and drier than any barn. No norther could touch it. By spring, they had to be kept away as the cavern might collapse, and did so at least once. The pile was torn down enough to make it safe, then the cows finished it off. The straw pile’s legacy after two to three years was watermelon, cantalope, cucumbers, etc.—more than could be gathered. Talk about an organic garden of straw and cow manure.

The harvest lasted about seven days, the wheat being hauled six miles to town slowed things quite a bit. About 6,000 bushels went into the oat granaries. Amazingly, the work became easier as skills improved. Everyone was paid as agreed. There were no accidents and the hay-hauling four high schoolers had new muscles to show their coach.

Life returned to normal. Row crop orange cane for silage needed cultivation, some of the stubble needed breaking for next winter’s grazing. The depleted larder began to be replenished as canning resumed.

To be continued.