Deering Harvester Company formed another major root of International Harvester Company. When William Deering became involved in the harvester business, Cyrus Hall McCormick had been at it for about forty years. No wonder the McCormicks viewed Deering’s phenomenal sales and growth with apprehension. Deering had a new machine — the Marsh Harvester.

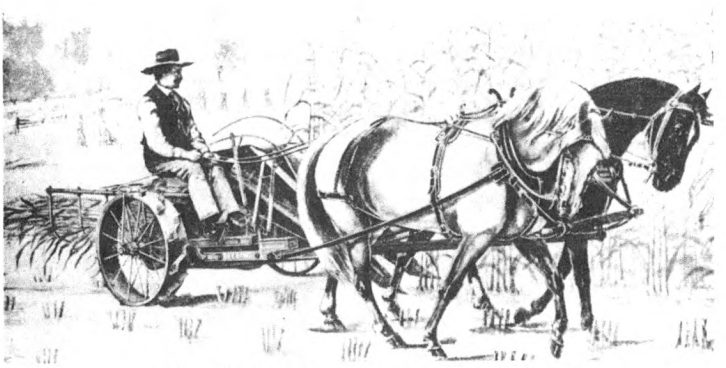

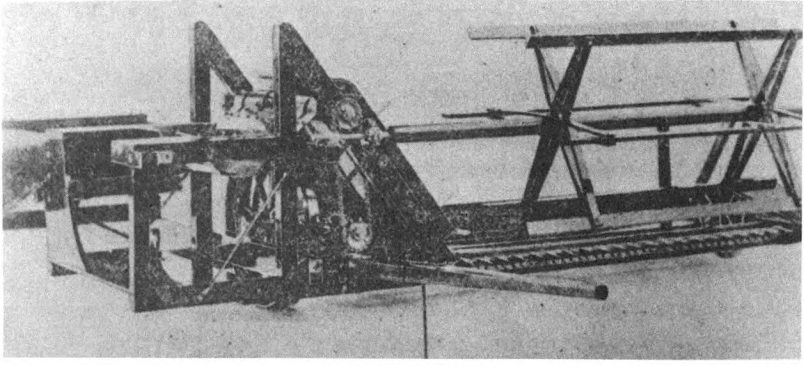

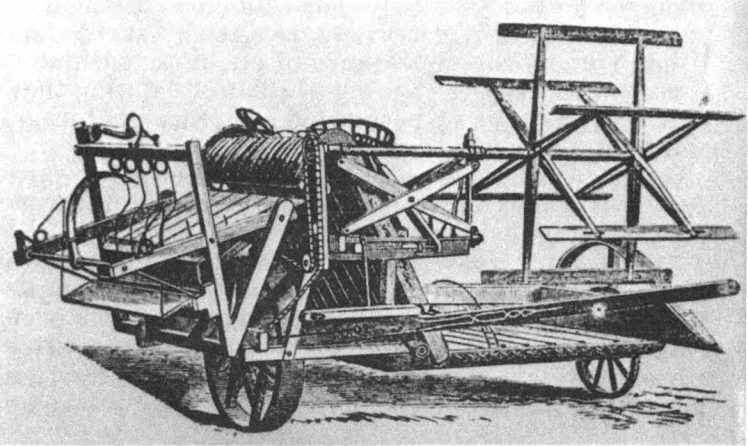

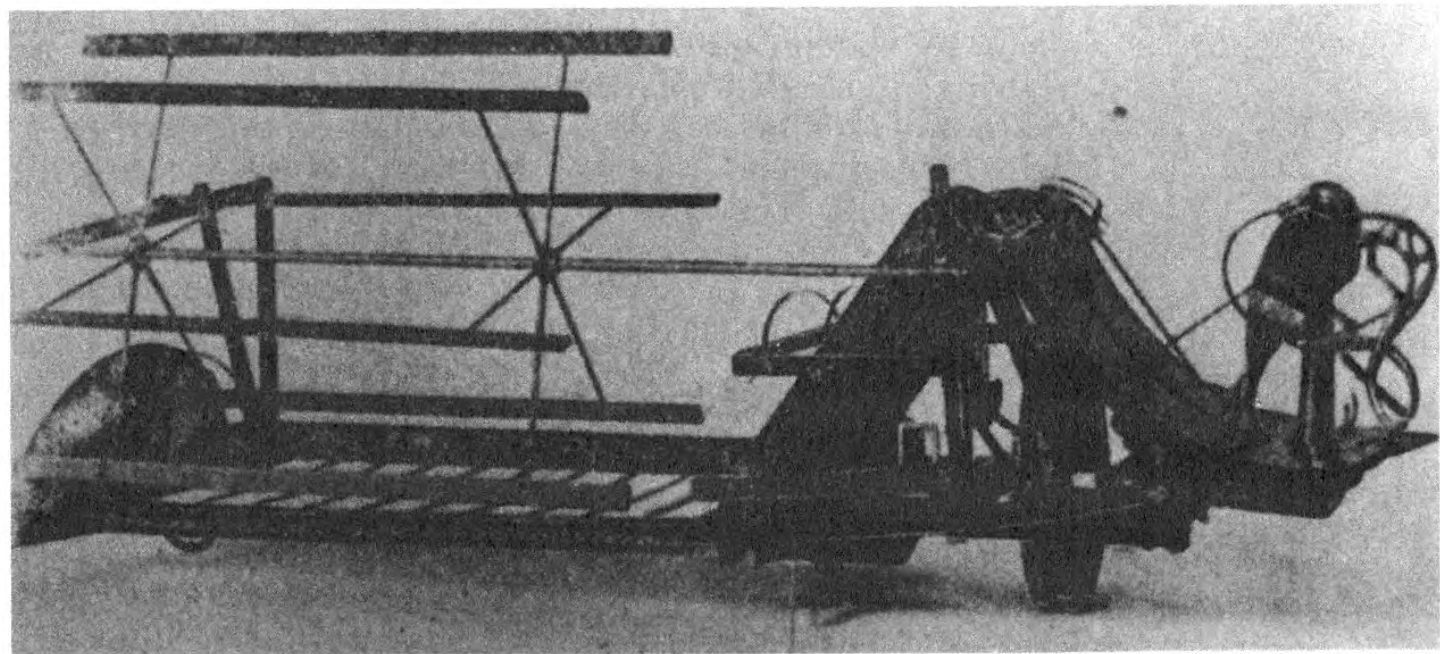

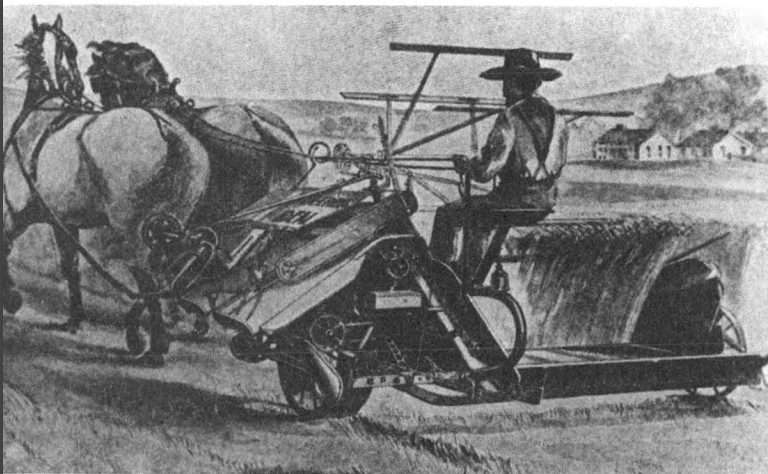

While following the basic principles of McCormick’s early machines, the Marsh harvester went a little further — now the binders could ride with the machine. By a new system, the grain was elevated over the drive wheel to a receptacle. Two persons bound the grain at this point, thus eliminating the back-breaking job of picking the grain up from the ground for bind ing. Before delving into William Deering’s role in the harvester business, it is necessary to begin with the development of the Marsh harvester.

The brothers, Charles W. and William W. Marsh of Shabbona Grove, Illinois stand alone as inventors in the development of the harvester. C. W. Marsh was an agent for the Mann harvester in the 1850’s. This particular machine was built by Haskell, Barker & Aldridge of Michigan City, Indiana. The Mann machine conveyed the grain to a wooden box above the drive wheel. An attendant operated a revolving rake to sweep the gavels of grain to the ground. Charles Marsh first conceived the idea of mounting a grain receptacle and binding table on the machine so that the binders might ride as they performed their duties.

In 1858 the Marsh brothers built their first machine, adapting it to a Mann harvester, and sup plementing it with such other parts as could be fitted to their purpose. A patent for this machine was issued on August 17, 1858. During the harvester’s brief hey day, it was changed very little from the original design.

The Marshs ineptitude concerning the fine points of patent law was compounded by the errors of their patent attorneys, and some misunderstanding on the part of the patent examiner. Had the patent been properly drawn, the Marsh harvester would have produced immense royalties for its inventors. As it was, the patent was subject to some costly infringement suits, particularly the suit with McCormick. In defense of their claims, the Marshs spent some $60,000 in legal fees, yet finally lost their case. A second harvester was erected in 1859.

A second harvester was erected in 1859. Its successful operation aroused much enthusiasm and buoyed the morale of the inventors. For 1860, they at tempted to build 12 machines. Castings were poured at DeKalb, machine work was done in Chicago, and some forged parts were made by local blacksmiths. Too many parties were involved with building the machine, and parts went together poorly. Only two of the machines were at all useable, and by harvest’s end, nearly everyone had given up on the idea.

At this point, providential help came to the brothers Marsh. Lewis Steward of Plano, Illinois saw one of the 1860 machines work, and was convinced of its Rossibilities. During the winter of 1860-61, Wallace larsh and John F. Hollister, a relative of Steward, built a much heavier machine. It was put on the market in 1863 by Steward & Marsh at Plano.

The Marsh brothers sold a one-third interest in their patents to Champlin & Taylor, a couple of speculators, in 1865. About the same time, John D. Easter of Chicago was granted an exclusive license for certain states at a royalty of $7 per machine. Champlin & Taylor soon sold their interests to Emerson, Talcott & Company. Easter took Elijah H. Gammon, a retired Methodist preacher, as his partner. Easter & Gammon contracted with Emerson, Talcott & Company and the Springfield, Ohio firm of Warder, Mitchell & Company to build their machines. Some historians report that Gammon was involved with the Marsh harvester as early as 1865, and had 100 machines erected at the Beloit, Wisconsin firm of Parker & Stone.

The Marsh Harvester Company was organized at Sycamore, Illinois in 1869. Gammon and Steward were now in control of the Plano factory, and the Marshs decided to strike out on their own. J. D. Easter formed his own selling organization in Chicago. Against this background, William Deering entered the harvester business in 1870.

Gammon retired from the pulpit because of a weak voice. He then became a reaper salesman, and proceed ed to amass a substantial fortune. The capital outlay for the harvester business was still a great strain on Gammon’s purse. While pondering how to raise more money, William Deering, an old acquaintance from Maine, appeared on the scene. Deering was in dependently wealthy from a wholesale dry goods business. He had $40,000 of extra money that he wish ed to invest in Chicago real estate. Gammon and Deer ing struck a deal — Gammon had found the needed capital, and Deering had found an investment.

Two years later, in 1872, Deering paid Gammon a visit. The books showed a profit of $80,000. Deering requested that he be made a partner. By 1873, Gammon became ill and asked Deering to move to Illinois and manage the business. Deering consented to be the manager for one year only, but Gammon remained in poor health. Deering later reminisced that “at the time I didn’t know the appearance of our own machine”. Gammon sold out to Deering in 1880, and during that year, Deering took up permanent residence in Chicago and built a large factory.

Gammon then aligned himself with Lewis Steward and W. H. Jones and organized the Plano Manufacturing Company at Plano, Illinois.

The Marsh harvester as such, was soon relegated to history. It represented the transition from the reaper to the grain binder, but demonstrated the basic principles necessary to carry the grain over the drive wheel. As such, the Marsh machine was the forerunner of the binder. It remained for others to develop reliable tying devices. The Marsh people were very receptive to new inventions and offered their machines to inventors at cost.

James Gordon did much of his experimental work on a Marsh harvester. His 1873 machine promised so much success that several were built and sold for the 1874 harvest. The same year, Deering urged that at least 100 of these wire-tie binders be built for the 1875 harvest. All 113 machines thus built were unsatisfactory, and were returned to the factory. It should be noted that these experimental machines had no effect on the “harvester” market, and represented a much smaller loss than was suffered by the Marshs under similar circumstances.

For 1876, Gammon & Deering’s machine was greatly improved, with several hundred being sold. This machine seemed to assure Deering’s success in the binder business.

Early in 1878, Deering and an associate were invited to the Parker & Stone factory at Beloit, Wisconsin. This firm had built a few Appleby twine binders. Two machines were bought and shipped to Texas. These were so promising that a formal agreement was drawn up in November of that year.

John F. Appleby was born in Oneida County, New York in 1840. While he was at an early age, the family moved to Wisconsin. While just a boy of eighteen, Appleby began experimenting with a self-binder. These experiments progressed but little during the next few years, due to a lack of money. Several years of service in the Union Army delayed experiments even longer.

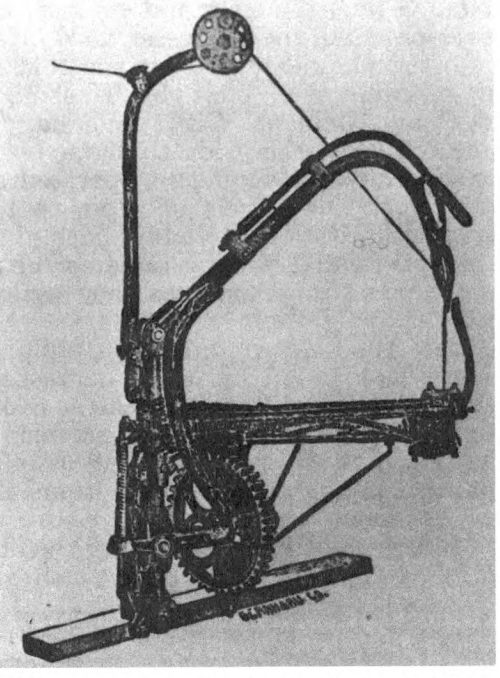

In 1865 Appleby built a wire-binder which operated fairly well. He received his first binder patent in 1869. Experiments continued, with improved machines com ing out each year. Parker & Stone at Beloit built a number of wire binders under Appleby’s direction. All involved were anticipating great success. During some 1873 field trials, objections were raised to the wire band, with fears that small pieces of wire might be swallowed by the farm animals, causing death or serious injury.

These fears prompted Appleby to investigate the possibility of tying with twine. During the 1875 harvest, a twine binder was tried out with excellent results. A repeat performance followed in 1876, and four machines were readied for the 1877 harvest. Early in 1878, Gammon & Deering bought a shop right to the Appleby twine binder, and launched a new machine that once again revolutionized the harvesting industry.

For 1879, Appleby improved the Deering binder by the addition of an “elastic compressor”. It provided uniform bundles in light or heavy grain. Lugs were added to the drivewheel the same year.

The shop license from Appleby permitted Gammon & Deering to build these machines on a royalty basis. At the close of the 1879 harvest, many of these machines were performing quite well. Deering became sole owner of the company in 1880, and decided to build 3,000 machines for that year’s harvest.

The new Deering twine binders were all sold, but a new problem arose. Farmers were upset over their twine bill. At the time, only three cordage mills in America could make twine. Deering discussed the situation with Edwin H. Fitler of Philadelphia. Fitler was reluctant to add the necessary machinery for twine-making until he learned that Deering was placing an initial order for ten carloads of twine. Within a few years, twine prices dropped drastically, reducing the farmer’s earlier outcries to some occasional grumbling. Deering, for his part, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars experimenting with various twines — primarily in an effort to lower the price.

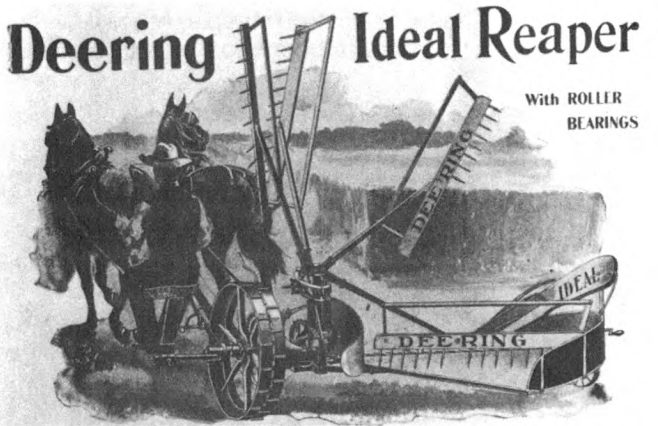

Deering’s rise to prominence was kept alive by constant innovation. The Marsh harvester with the Appleby binder was redesigned and lightened in 1883, providing a machine that would do the same job with less weight and draft. An all-steel binder was introduced in 1885; it had greater strength and less weight than the wooden machines. The all-steel binder was further lightened in 1889, and roller bearings were added in 1891.

During the 1890’s, Deering attempted to build a low-down binder sim ilar to M cC orm ick’s “Bindlochine”. This outfit, nicknamed the “Prairie Chicken’’ never went into production. A corn binder was first marketed about 1894.

By 1890, McCormick and Deering were leaders of the harvesting industry. Deering proposed to sell out to McCormick in 1897, but the plan failed when the necessary capital could not be raised. Competition resumed as fiercely as ever. Deering anticipated McCormick in hay rakes, binder twine, mower knives, malleable castings, and was building a steel rolling mill. In addition, Deering had acquired vast ore and timber reserves. There was no question that Deering was closing the gap. Thus the stage was set for Deerings 1902 entry into the International Harvester Company.