By: Ed Maas

Classic Farm and Tractor – January/February 2020

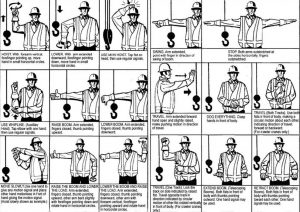

“And…down easy…easy…aaaaaannnd…hold that,” said the man over a two-way radio as he hooked the lifting straps to the crane. He had instructed the crane’s operator to lower the hook block and then stop completely.

It doesn’t seem quite “by the book,” but that’s the way many riggers and crane operators will communicate when lifting and moving materials on construction job sites. Nowadays, they use a combination of two-way radios and hand signals. There are universal hand signals for all crane operations, but with the size of the equipment and the huge projects being built, there are many times the operator doesn’t even see what he is lifting or even the fellow directing him.

This story is about some of the equipment used in the construction and mining businesses, the changes made to it over the years and the capabilities of some of the modern pieces versus the old. It’s too broad an area to cover everything in one story so in this issue, we’ll look at cranes and, in particular, those referred to as “crawler cranes” or “lattice-boom cranes.”

As I contemplate retiring soon after 45 years in trucks, I fell blessed to have spent much of that time hauling construction materials and machinery. It has always provided a variety of experiences, some simple and some completely off the scale in the “wow factor”!

How did they get that up there?

Have you ever looked at a structure such as an old church steeple or a grain elevator or even a huge skyscraper and wondered just how they got the material way up there? Some of you may have seen images of a primitive hoist with a windlass or horse-powered pulley system where a small tripod of timbers hung over the edge of a roof and, as the rope was wound up, the material raised slowly to the top. Those practices were used considerably well into the last century. But now, with larger equipment, larger projects and “tons” of new rules and regulations from OSHA and other agencies, it is a much more involved business.

The larger the job, the bigger the crane. Right? Sometimes that’s true. But, it’s more about how heavy of a load a crane must

lift and how far it must reach. For instance, it’s not uncommon to see a tall crane set up next to a building that may only be one or two stories high. They may be using it to place a large air conditioning unit in the center of the roof or perhaps place materials in the center of the building for a construction project.

To figure a crane’s available capacity for a lift, one must first understand the physics of it. The easiest way to picture it is this—pick up a brick and hold it straight out in front of you. It’s tough, isn’t it? Now, take that same brick and hold it above your head. Much easier. A crane works the same way. The farther out from the center of the crane, the more strength is needed and the tipping point of the crane changes dramatically.

Some examples

One of the world’s largest cranes is owned by Deep South Cranes in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It has a maximum capacity of 2,500 tons and up to 500 feet when all its boom sections are used. But, as one user said, “Even though that’s a big crane, 2,500 tons, when you take 400 tons and put it out the length of a football field, we’re at 95 percent capacity for that crane right now.”

Here’s another example. For more than a dozen years, I drove a truck delivering building steel and on it was mounted what is referred to as a “knuckle-boom” crane because of the way it folded up behind the cab for travel. It was rated at a maximum of 13,600 pounds and would reach 35 or 40 feet out or up. However, at that distance horizontally, the capacity dropped to only a few hundred pounds. I don’t recall a time when I ever lifted anywhere near the maximum load. A load that size would have needed to be alongside the fuel tanks, mere feet away, to achieve that.

The crane’s operator is responsible for using the indicators and charts provided and there are many highly technical safety systems in place with their buzzers or bells to warn of potential overloading, being “out of level,” or even watching wind speed with an anemometer. Most cranes these days will automatically stop any function that would result in possible tipping. At that point, an operator would have to lower his load or raise the boom. Remember the example with the brick in hand. The closer to the center of gravity, the easier to hold and balance.

Some of you may have even seen this crane and never thought any more about it. In this picture, it is being “walked” to a different area of a job site—in this case, it’s an ethanol plant in Janesville, Minnesota. The term “walking” is a safety procedure to be followed when a crane is moved. Another operator, or other designated worker, will walk slightly ahead of the crane as it travels, both guiding the crane operator and warning anyone who might be in the crane’s path. This is a Manitowac model 999, a “Triple Nine,” and one of many Manitowac cranes owned by Fagen, Incorporated. Fagen is a large contractor based out of Granite Falls, Minnesota and has constructed a large percentage of the ethanol plants across the country. They’ve also been a part of many power generating plants and wind tower construction. The “Triple 9,” when assembled for maximum height, is 400 feet tall and has a lifting capacity of 250 tons. For transporting, it would breakdown into 12 or 13 semi loads—maybe a counterweight and a track assembly on one load, a few loads with more counterweights and boom sections and so on. Most brands and models are similar.

“Some assembly required”

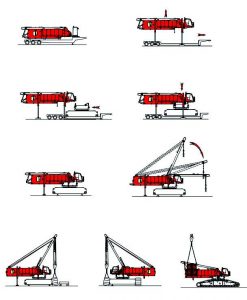

Cranes must be disassembled to move them and then put back together on the next project. Although crawler cranes can move around a construction site, there is often much planning as to where it will be erected. In this way, its placement will cover as much area as possible and it will minimize on-site moves in the future.

Many modern cranes, even those capable of lifting hundreds of tons, are designed to be used in their own disassembly. That includes separating boom sections, lifting off counterweights, even lifting its own tracks off each side and sitting each piece on a truck as it proceeds. The crane “house” is the section where the cab, engine, winches and other mechanical items are in the base. It is the last component and is left standing on hydraulic legs, ready to have a truck back in under it and lower down onto the trailer. This load will require oversize and overweight permits to move on highways because of the weight and dimensions of it.

Most job sites big enough to need a crane this size will have smaller cranes and other equipment to assist in a “breakdown.” The disassembly goes much faster when there is no need to re-rig everything. While I have only helped a few times, and only on parts of each breakdown, I marvel at the design and the way the process works!

Heavy cranes can be found anywhere. And often, it isn’t the weight so much as the height. But to reach the heights, a crane needs more boom and that means more capacity. Wind towers are a good example. The height isn’t at issue as much, until you consider the weight being set up there. A typical windmill can be well over 300 feet high and weigh 160 tons to 325 tons. That’s a lot of weight up in the air! Many construction companies bought larger cranes primarily with the wind farms in mind.

There are many oil refineries in the south, so there are also many large cranes. And, as you would expect, many crane operators. So, it should be no surprise that many of the seasoned operators come “equipped” with a southern drawl. They travel with the work and the work may keep an operator away for extended periods. Still, one of the things that draws someone to a certain job is variety and I’m probably the same way. It’s kept me in trucks for 45 years!

The author can be contacted by email at: [email protected]