Everything in life has its challenges. The history of mechanized agriculture is certainly no exception. Although the history of J. I. Case Company is seen here through the product lines, numerous other companies appear along the course of this 150 year odyssey. For example, the 1919 acquisition of Grand Detour Plow Company gave J. I. Case an ostentatious place in the production of plows and tillage implements. Following this came the purchase of Emerson-Brantingham. Following the latter company to its roots is almost like a “ who’s who” of the implement business. Then, the acquisition of Rock Island Plow Company brought with it a history of men and machines going back to the 1850s.

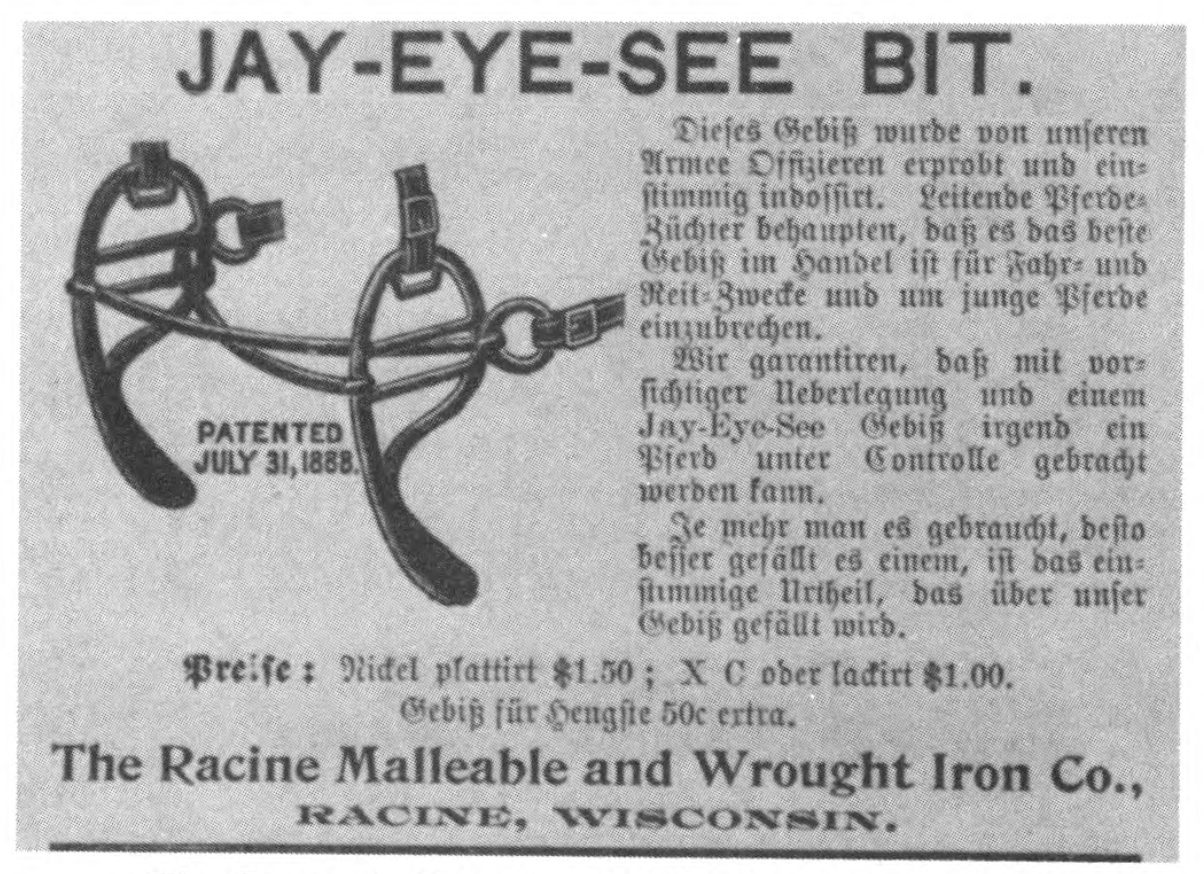

Many other purchases, takeovers, and acquisitions took place during the 150 year history of the small thresher company organized by J. I. Case. Of special significance, is the 1985 merger of J. I. Case with International Harvester Company. From a historical perspective, Cyrus Hall McCormick was developing his reaper during the 1830s, just as Jerome I. Case was bringing his ideas from daydreams to a reality. What if? This simple question could be asked about many phases of history, but for our purposes, it could be asked, “What if Case and McCormick had decided to work together?” or “What if J. I. Case had deviated from his singleminded goal of building threshing machines, and added other implements during the 1840-1870 period?” Another question might be, “What if J. I. Case had not located at Racine? Did his geographical location underpin his success?” These and many other questions could be asked, but even the most detailed research will probably never give any answers.

Throughout the course of this research, establishing precise production dates of many Case implements has been very difficult, and in numerous cases it has been impossible. One of the reasons is that Case apparently did not keep detailed production records, at least not for public consumption. The company did maintain accurate records on its production, and offered detailed parts books on its machines. In almost all cases, modifications to the specific implements were noted by the serial number only. Lacking this information, it is impossible to ascertain from the serial numbers alone when a specific product was built. Therefore, we have attempted to reasonably establish the production periods of various implements. Should errors or discrepancies appear, kindly inform us of same so that corrections can be made in future editions.

Throughout this narrative it has been our goal to show the evolution of the farm equipment industry, specifically that of J. I. Case and its related companies. A special emphasis has been placed on the development of the Case threshers, steam traction engines, and farm tractors. For these classifications, considerable backup material remains, including rather specific production records.

No doubt there will be some readers who wish there had been more illustrations of automobiles, and fewer illustrations of say, plows or harrows. For some sections of this book, we had more material available to us than for others. Sometimes this was a subjective decision on the part of the Author, as we attempted to present an objective picture of J. I. Case product development. Then too, there is always the constraint of time, plus the page limitations of a book as limiting factors. As the Author has stated in previous books, the ultimate decision of whether this book is seen as a contribution to the repertoire of agricultural history remains with you, the reader. Should our readers be able to supply specific dates, illustrated materials, or other items for possible use in future editions, please address your correspondence directly to the Author. Likewise, should you detect errors or omissions, please let us know.

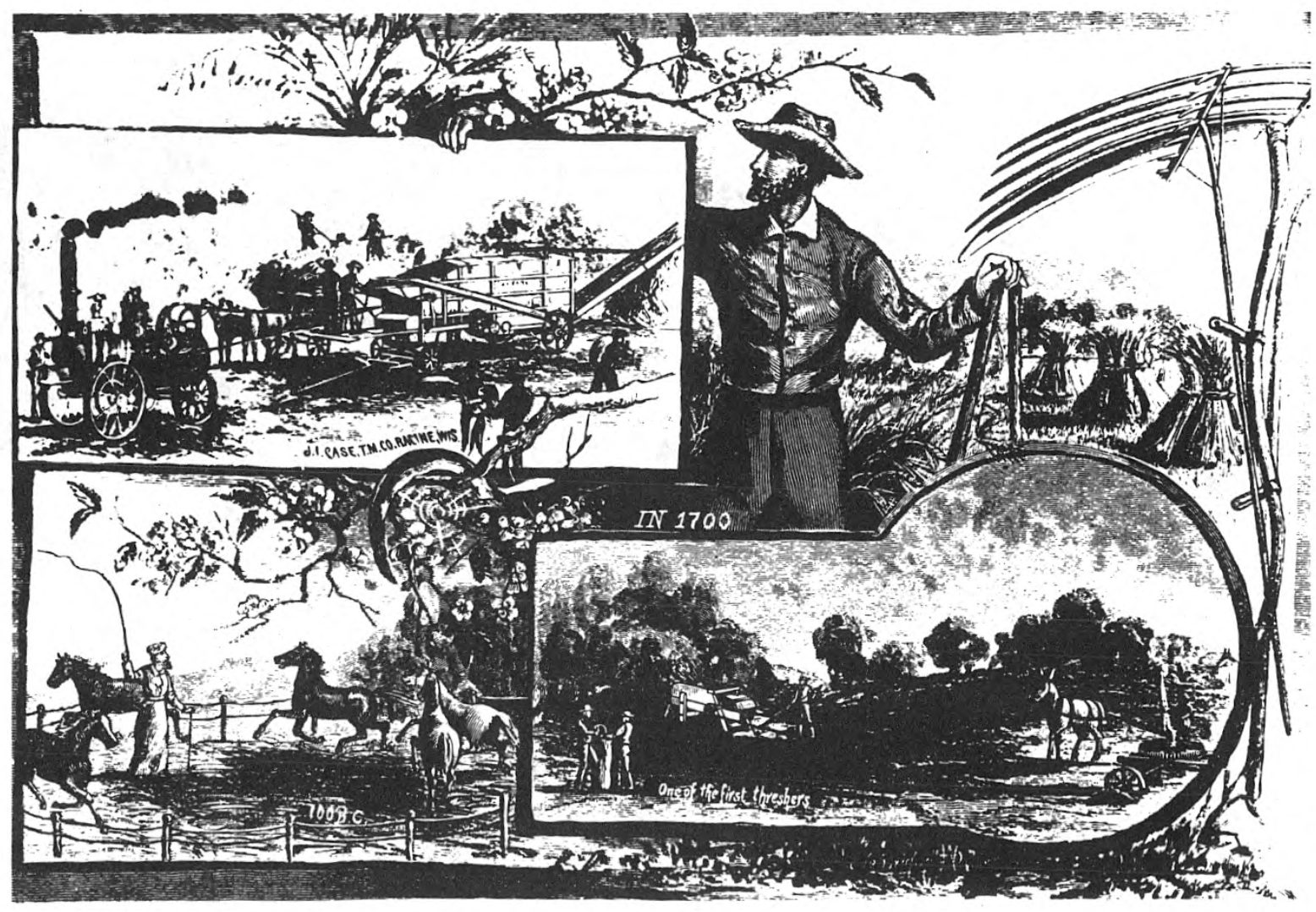

American agriculture of the early 1800s followed virtually the same farming methods of previous centuries. Then in the 1830s the Pitts brothers developed a crude thresher. McCormick patented his reaper about the same time, and the partnership of Deere & Andrus eventually yielded the steel plow. By the end of the nineteenth century, America would move from an agrarian to an industrial economy, largely due to the development of the plow, the reaper, and the thresher. The demand for these three basic machines created a need for workmen and mechanics in newly established factories. The consequent shift from labor intensive farming methods freed up thousands of men for factory work.

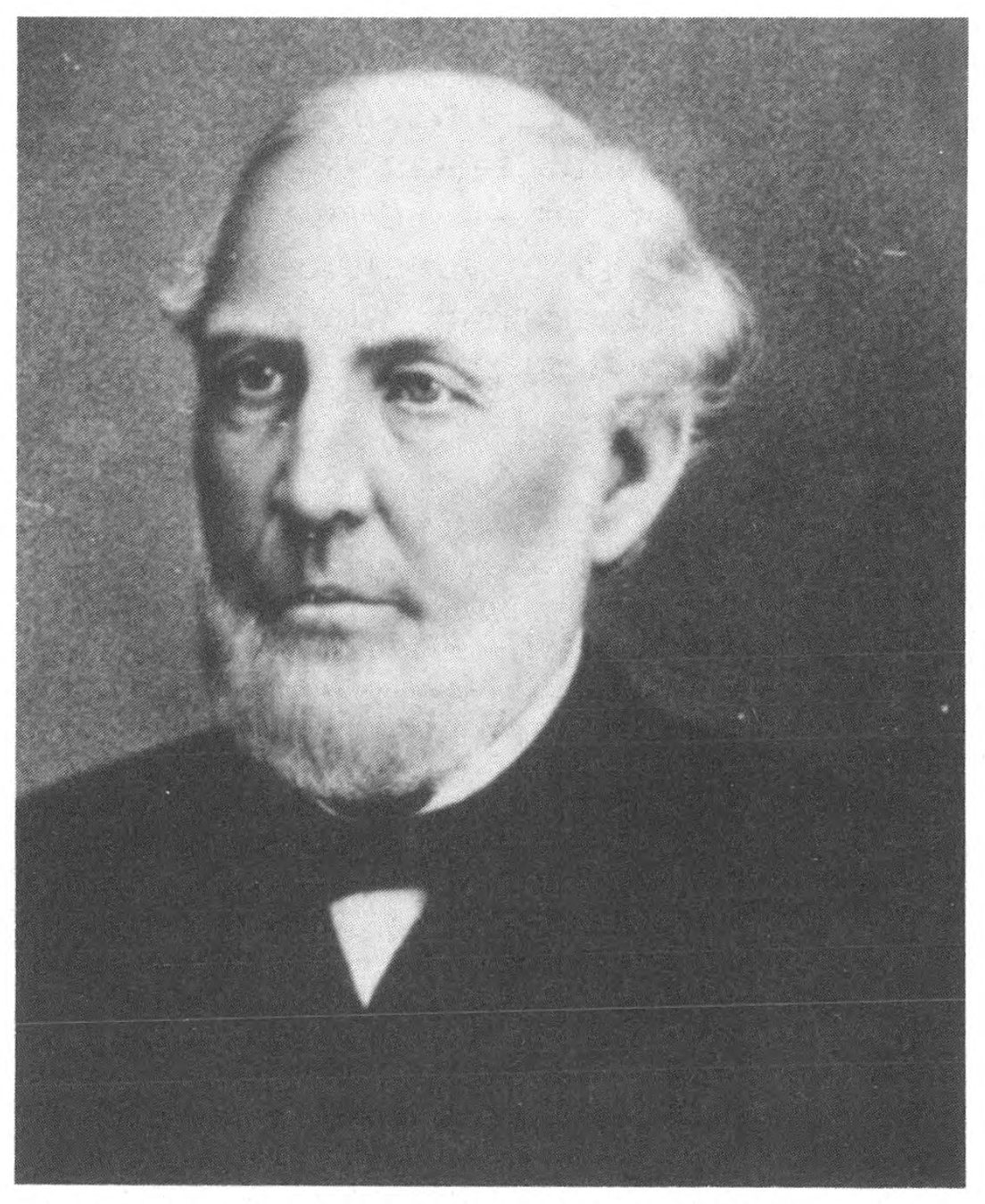

When Jerome I. Case was born in 1819, Abraham Lincoln was already ten years old, as was Cyrus Hall McCormick. Lincoln took up the practice of law and McCormick spent much of his life developing the reaper. For Case, the threshing machine held a special interest, and sometime during the 1830s young Case induced his father Caleb to purchase a groundhog thresher. This was a simple machine that separated the grain from the stalk but still required hand winnowing. Caleb Case became a selling agent for this machine and for several seasons young Jerome traveled the countryside of Oswego County, New York doing custom threshing.

An avid reader, Case followed the Genesee Farmer and other agricultural journals of the day. (This paper was a direct ancestor of the Country Gentleman.) During 1841 young Case read of the wonderful wheat crops being grown near Rochester, Wisconsin. Owing in part to these accounts, young Case was determined to leave Oswego County, New York and settle at Rochester, Wisconsin. Left behind were several older brothers, and his parents, Caleb and Deborah Johnson Case. (Jerome’s mother was distantly related to President Andrew Jackson.)

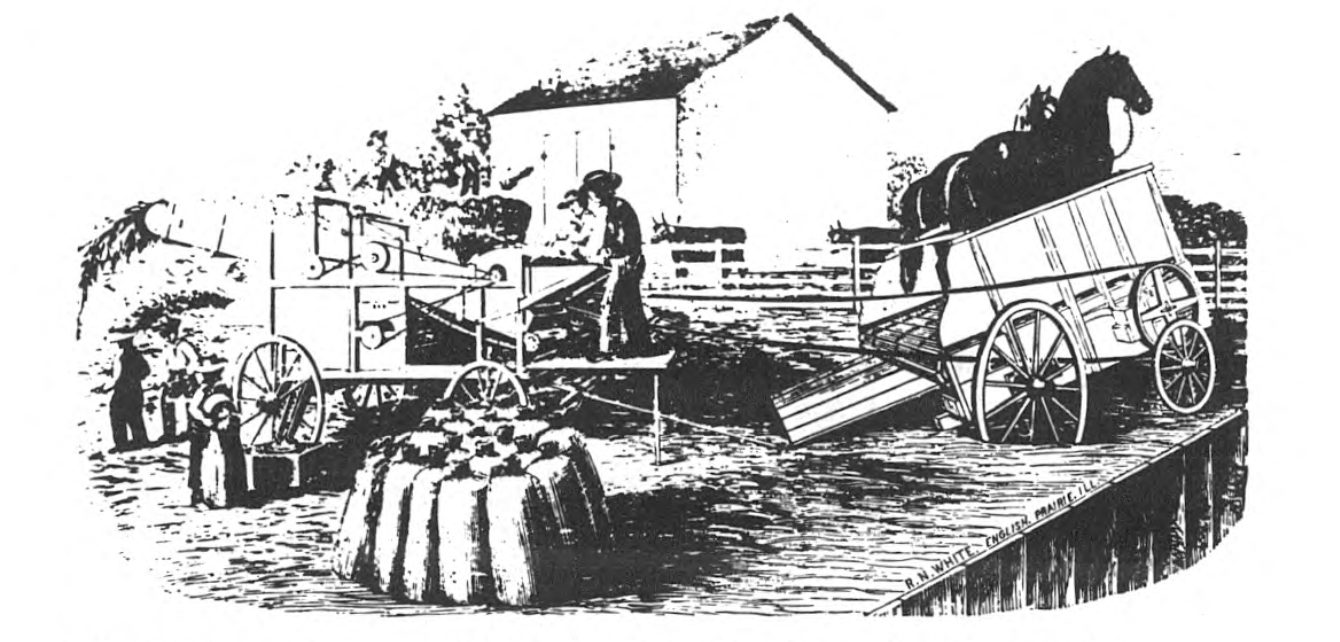

So, in the summer of 1842, J. I. Case bought six groundhog threshers on credit. The plan was to sell five of them along the way and keep one for his own custom threshing business. Leaving Oswego on the vessel Vandalia, Case eventually docked at Chicago, bought a team and wagon, and departed for Racine County, Wisconsin. On the trip from Chicago to Rochester, five machines were sold. During the journey Case used the sixth unit for a substantial amount of custom work. Shades of autumn were evident when he arrived at Rochester, in late 1842.

With definite thresher improvements in mind, Case set about the task of revamping his thresher in the winter of 1842-43. First and most important, Case wanted to combine the groundhog with a fanning mill so as to thresh and clean the grain in a single operation. Already in 1837 the Pitts brothers, Hiram and John, of Winthrop, Maine had patented such a machine. Shortly thereafter Jacob V. A. Wemple received a similar patent, and the latter then went into partnership with George Westinghouse of Schenectady, New York. Case expressed similar goals and was assisted dining the first winter’s work by Richard Ela. This man had several years of experience in building fanning mills and had established a successful business at Rochester. Between Ela’s help and a rented bench in a local carpenter shop, Case set himself to the task. The initial results were a disappointment, and despite his efforts, the machine was not ready for the 1843 harvest.

In May 1844 farmers gathered at the Cherry Hill Farm of local resident Henry Cady. The machine worked; clean grain came from the spout, while the straw and chaff were delivered in a separate pile.

It must be noted that threshing in May was not at all uncommon at this time. In fact, barn threshing remained in vogue, at least in certain areas, for another century. In practice, the cut grain was shocked, and after a suitable sweating or curing time, the sheaves were hauled to the barn for threshing whenever time permitted. Thus the winter months and other slack seasons were often occupied with threshing the previous harvest. Stationary or “ barn threshers” were available from a few companies as late as the 1930s.

Case and his new machine did a substantial amount of threshing in areas of Racine County during 1844. Several farmers wanted to buy a similar machine. Having already decided to become a manufacturer instead of a thresherman, the next step was to secure a shop and water power.

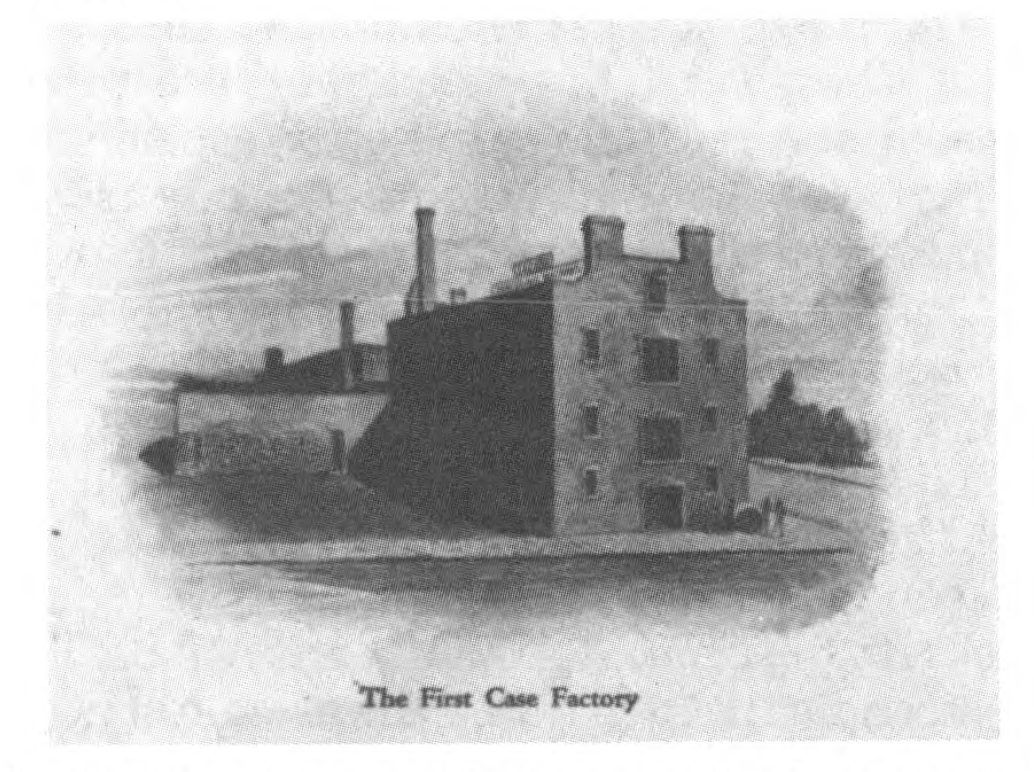

At this juncture J. I. Case and the organized powers of Rochester parted company. Water power rights were closely held by a small group of Rochester residents, and they refused to allow rights for Case to build another millrace. Legend has it that the very next day Case hitched his team to the thresher, loaded up his tools and other belongings, and headed for the nearby town of Racine.

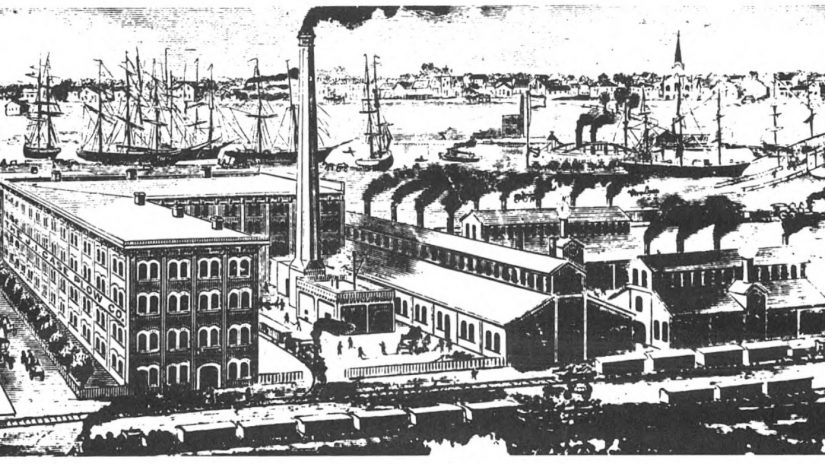

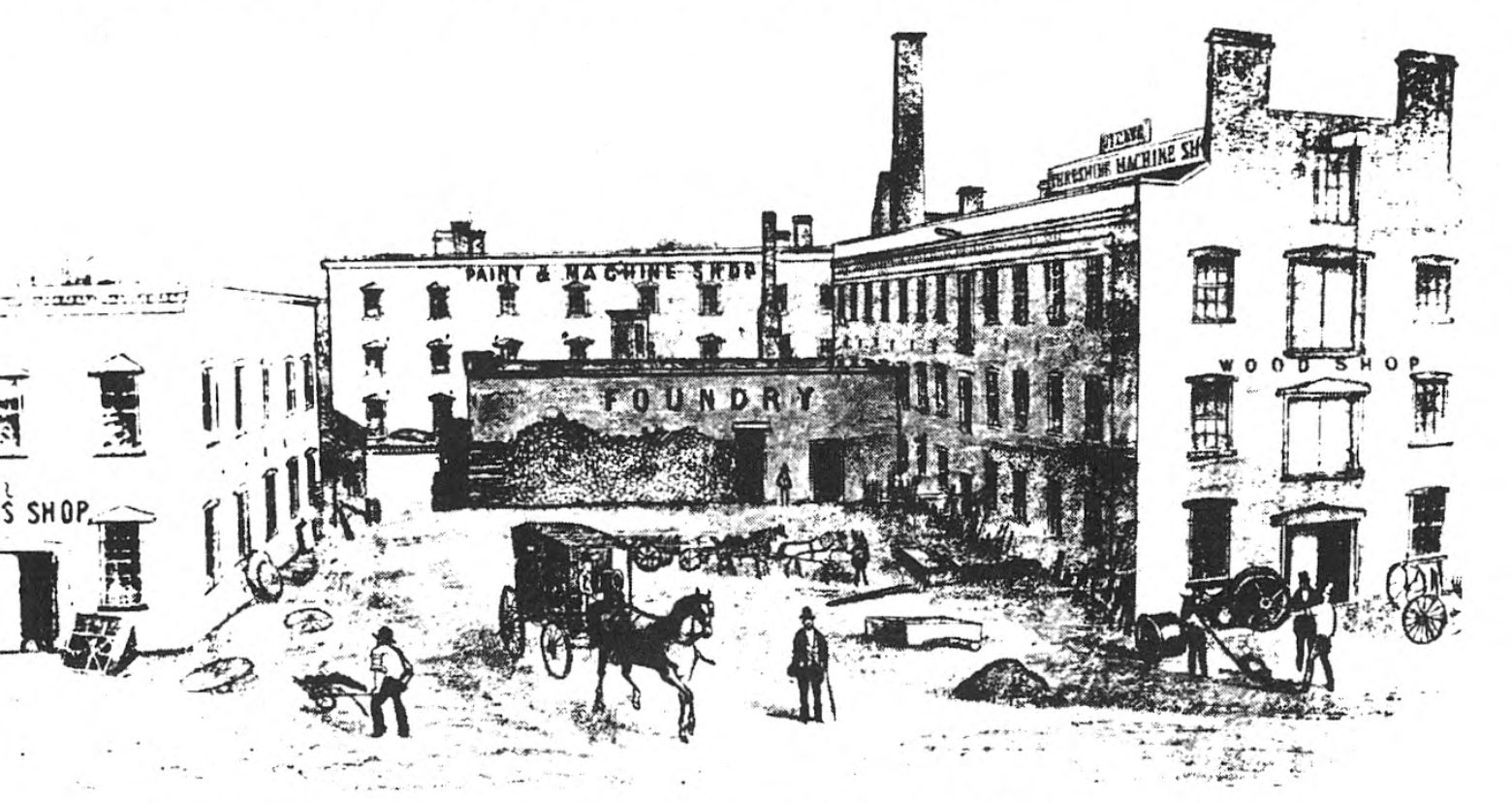

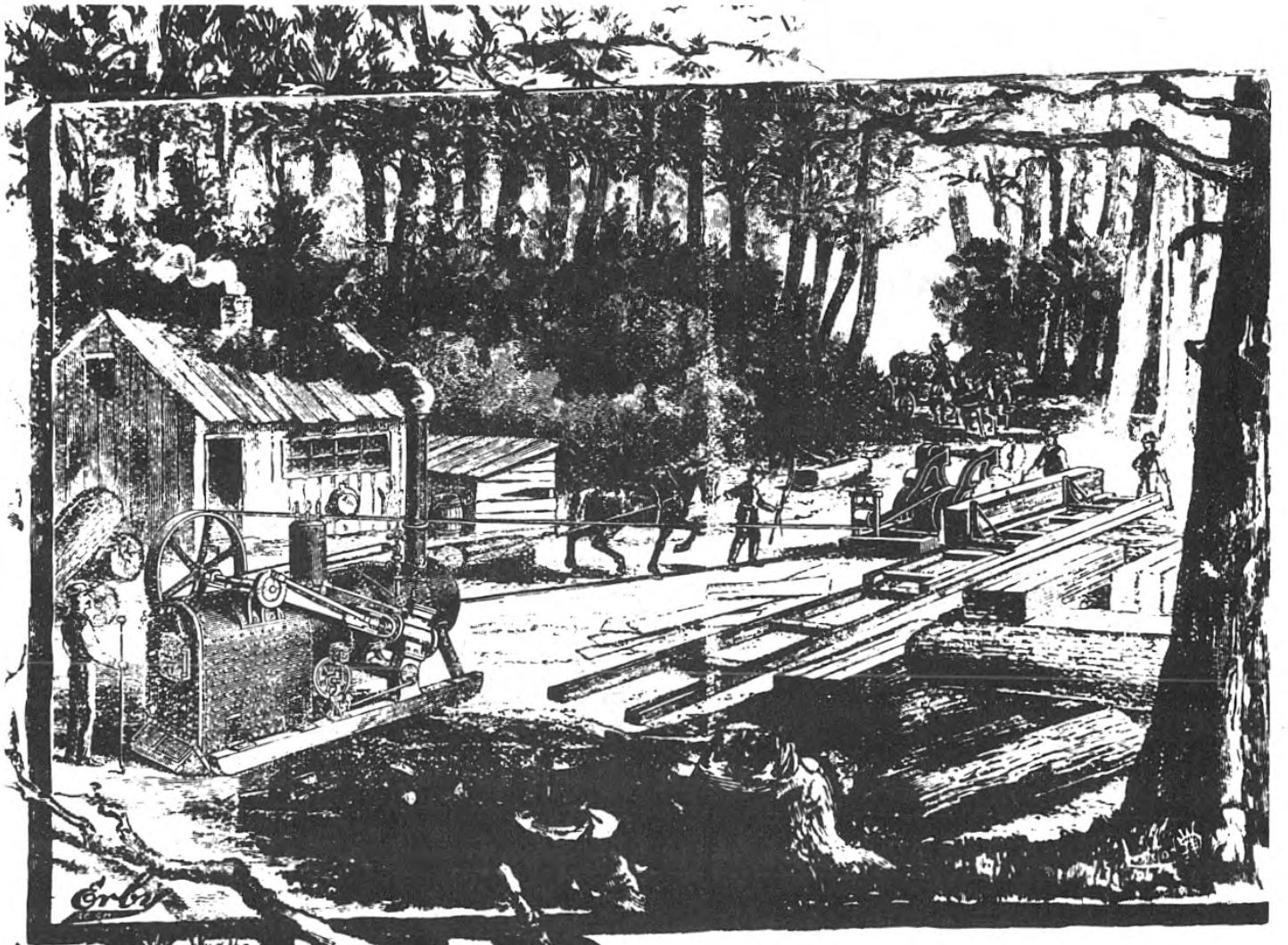

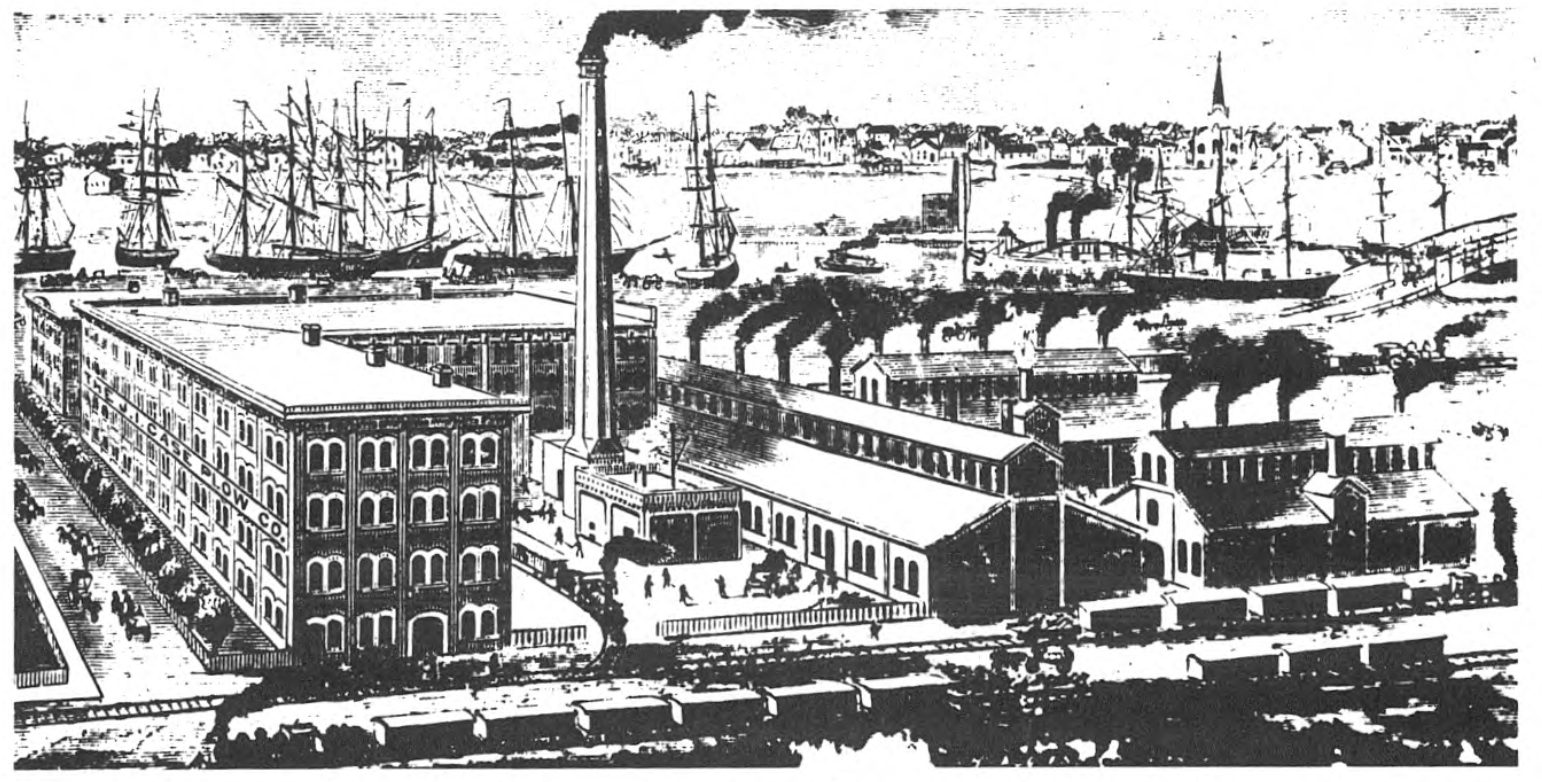

The Racine, Wisconsin of 1844 had a population of under 2,000 inhabitants. Case rented a small shop on the riverbank and began building threshers, but was never able to catch up to the demand. During the 1844-47 period Case established himself as a man of sterling character and an unswerving dedication to building the best possible machines. The profits from these first three years were no doubt ploughed into a new three-story brick factory building erected in 1847. Its 30 x 80 foot dimensions would provide ample manufacturing space, and the new factory was equipped with a steam engine.

With the completion of the new factory came a new title, “ Racine Threshing Machine Works, J. I. Case, Proprietor.” Then in 1848 came the first advertisement; a wall hanging which extolled the virtues of the new thresher. From this advertisement it is gathered that the revolving apron of the machine was being built under license from the brothers Pitts. Further improvements were secured under the Wemple patents.

Although little historical data remains, from all appearances, Case was not at all hesitant to purchase important patents or secure manufacturing rights thereunder. In this regard Case set himself apart from many of his contemporaries. For example, the reaper and mower industry was plagued with infringement suits almost from its beginning, finally reaching its climax in the ‘Great Reaper War’ of the 1860s and 1870s.

A perusal of the Northwestern Reporter, a synopsis of Supreme Court decisions for Wisconsin and several surrounding states shows virtually no suits where the company was forced to sue for payment on machines sold. Of those few cases cited, almost none of the defendants pleaded a general denial, claiming that the machine was either no good, or would not perform as warranted.

Particularly before 1900 however, it is not at all difficult to find court cases wherein certain steam traction engines, grain binders, threshers, and other farm machines were not paid for because they would not perform within the terms of the warranty or in some cases would not work at all. In those cases where the evidence tended to prove the defendant’s complaints regarding the poor performance of a machine, juries were likely to find for the defendant. Barring prejudicial error, higher courts were not likely to upset their verdict. Conspicuous by its absence was J. I. Case Company. Seldom was a suit for recovery appealed to a higher court, and even then, it appears that the defendant’s refusal to pay up could not be substantially claimed as a consequence of a faulty machine.

By 1850 a Case thresher was priced at $290 to $325, complete with a 2-horse tread power. Due perhaps to custom, an all-cash deal was uncommon. The standard practice was to pay $50 on delivery, $75 on the next November 1, another $100 on January 1, and the balance on the following October 1. This method of doing business was to cause immense problems for Case and other farm machinery builders. Collecting past due accounts was tremendously difficult and time consuming; one trip in 1849 yielded Case a total of $50 on outstanding payments due of $2,500. Then too, a fair number of shysters were about. In one instance near Janesville, Wisconsin Case went to see about $300 due and payable, only to discover that the debtor, thresher and all, had departed to an unknown western location.

The time payment plan for threshers, reapers, and other farm machines evolved from several different notions of the day. One reason appears to have been an inducement for the farmer to try out the machine without having to spend a great deal of money. The logical assumption was that once the farmer saw the immense reduction in manual labor and a consequent increase in productivity and profits, he would gladly make the payments and accrued interest.

A second reason for the evolvement of the time payment plan on farm equipment had its basis in the irregular and often unpredictable income of the farmer. Although this assumption had some basis in fact, the truth was that progressive and successful farmers were able to pay for what they bought, or at least had an established line of credit. Curiously, farm equipment manufacturers, Case included, continued to educate farmers in this way of doing business, even though this plan often worked to their own detriment. Many companies, including Case, were thus forced to establish their own Collection Department with men on the road full-time. Their single duty was to collect on obligations owed the company. This method of doing business tied up funds needed for experimental work, new facilities, and improved manufacturing methods.

Oddly enough, it was the newborn automobile industry of the early 1900s which brought an end to this business practice. During its early years, the automobile manufacturers generally sold for cash, leaving the buyer to secure his funding from the sock under the bed or from the local banker.

About 1914 Avery Company of Peoria, Illinois was the first of the old line thresher companies to break with tradition and announced a ‘cash only’ pricing policy. Most of the small fry tractors then popping into the picture operated under the same principle. By 1915 virtually no one would admit to maintaining the time payment policy that had been in effect for decades. Old habits die hard, and a few engine and tractor companies maintained a time payment policy until forced into a cash policy by the Great Depression.

Various accounts of J. I. Case portray him as being abrupt, occasionally gruff, and not well disposed to easy conversation. These deficiencies in personality were more them offset by forthrightness and honesty, plus a good sense of business management and first class mechanical abilities.

As previously noted, Case is notably absent from suits claiming his machine to be a non-performer. In the early days these matters were handled personally by Mr. Case. One such instance is often quoted, and must be related here:

A man near Marion, Indiana refused to make further payment on a Case thresher, claiming it to be incapable of threshing more than thirty bushels a day, and terming it a “ a Yankee humbug.”

Case personally went to Marion, hiring experienced men and teams. Getting the machine ready by noon of the appointed day, Case himself fed the bundles into the machine. In about six hours they had threshed 177 bushels of wheat, far more than Case had claimed for the machine in an entire day! That settled the matter, the buyer paid up, and Case returned to Racine.

In later years, perhaps about 1884, Case played out what has become a living legend of himself as a forthright and honest businessman. A farmer near Faribault, Minnesota had purchased a new Case engine and thresher. The thresher pulled too hard and would not deliver clean grain. He complained to the agent, and the latter attempted to make it work. Having no success, the agent contacted the home office at Racine. They sent their best trouble shooter, and after several hours he wired the company, recommending that they either supply a new machine or a refund. To this wire J. I. Case replied directly that he himself was heading for Faribault on the next train. Arriving in the afternoon, Case set to work on the thresher. Numerous times during the afternoon the machine was started and stopped. Finally, toward evening the old man asked the farmer whether he might have a sizable can of kerosene handy. Bewildered, the farmer soon returned with the flammable liquid. Without a word, Case doused the machine from one end to the other, and then touched a match to the brand new thresher. Even while the flames were still bright against the evening sky, Case put on his coat and hat, bowed to those present, and left for Racine. The next morning a new Case thresher was delivered from the nearby Faribault warehouse.

By 1852 the business had grown so much that he hired Massena Erskine to take charge of the mechanical department. His wife’s brother, Stephen Bull, became his personal assistant in 1857, and in 1860 Robert Baker took over the Collection Department. These men, collectively known as the Big Four, managed the company for many years.

During his lifetime J. I. Case saw a great many significant changes in the American nation. Born during the administration of President James Monroe, Case saw a succession in the White House that included Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. Railroads were built, tying the nation together with twin ribbons of steel. The telegraph was perfected, and this enhanced the rapid communication of information throughout a vast nation. Unquestionably, the coming of the railroad and the perfection of the telegraph were major factors in the growth of the Case enterprise, as well as that of all American commerce and industry. Now a farmer could not only order a machine over the telegraph wires, it would come in to the local depot, and a sight draft could be given on receipt of the thresher. When parts were required, if not in stock at the local dealer, a telegram and shipment on the next express train helped prevent lengthy breakdowns. In this and many other ways, the growth of American industry was keyed on a mutual need, and each segment was dependent on the other.

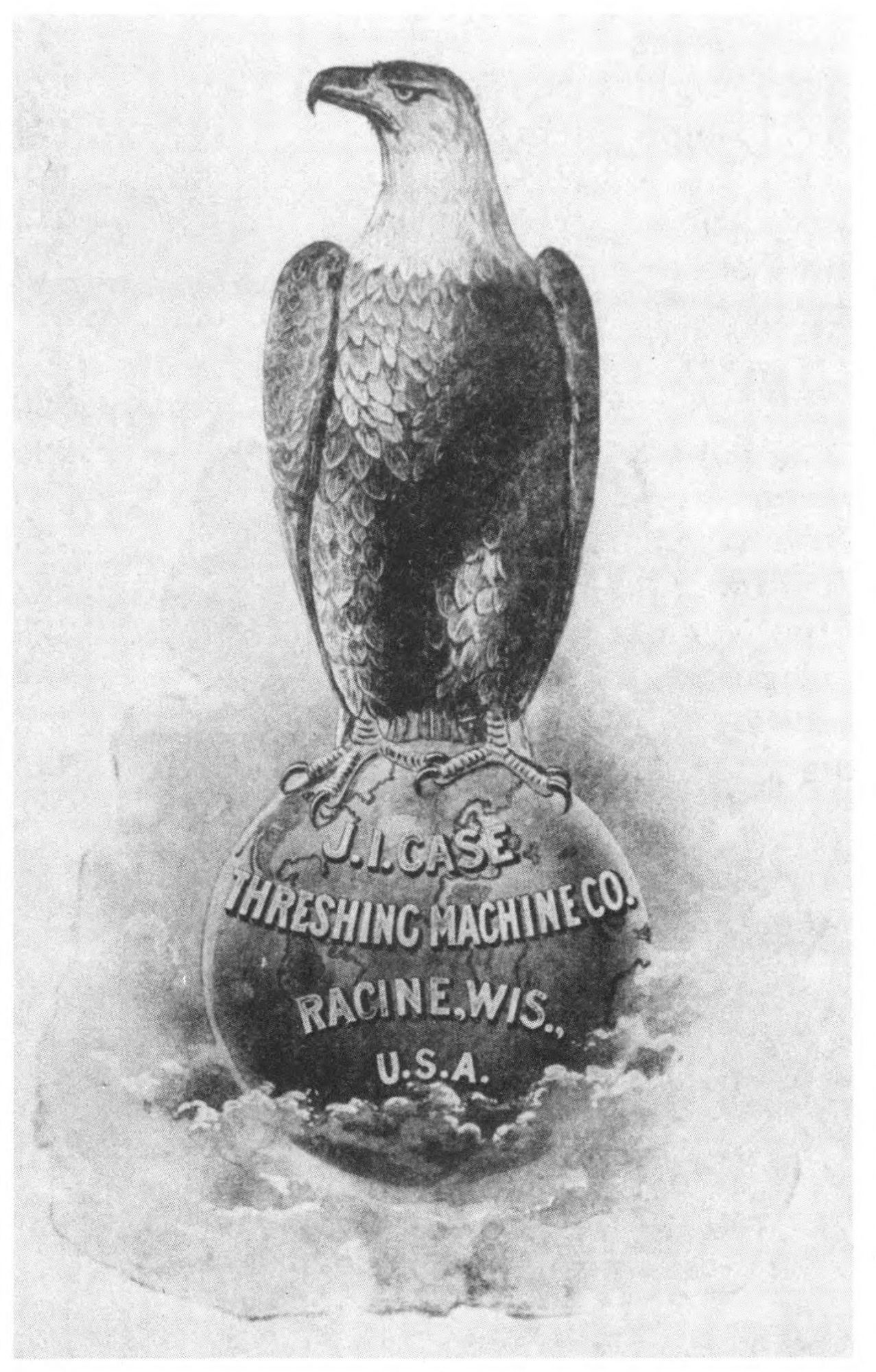

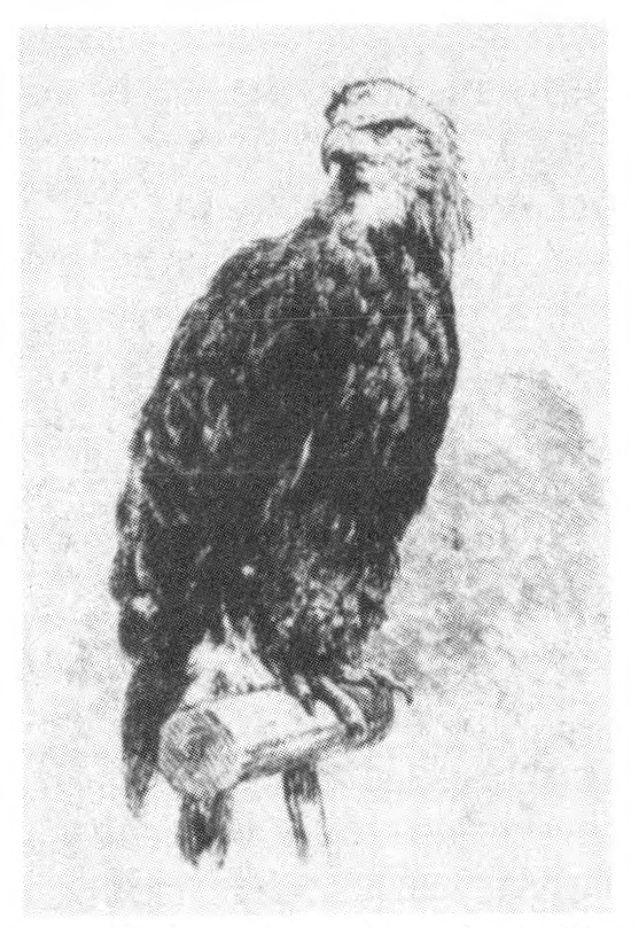

Sometime during 1861 Mr. Case was in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and was one of many spectators watching while Company C of the Eighth Wisconsin was being mustered. Their mascot was a bald eagle named Old Abe. Shortly after the end of the Civil War, the Case people were looking for a suitable trademark. Old Abe, the now-famous mascot of Company C was nominated, and adorned all J. I. Case machinery until recent years.

During 1869 Case announced the new Eclipse thresher. Gone was the apron-type separating system of earlier years. In its place came a raddle system consisting of an upper, open straw rake, with a grain rake beneath. The change was not completed initially; the older Sweepstakes apron remained available for a time subsequent to the introduction of the Eclipse. This plan had several advantages; it kept the risk to a minimum so far as the sales potential of the new machine, and secondly, it permitted the assembly and sale of parts already in stock for the Sweepstakes machine.

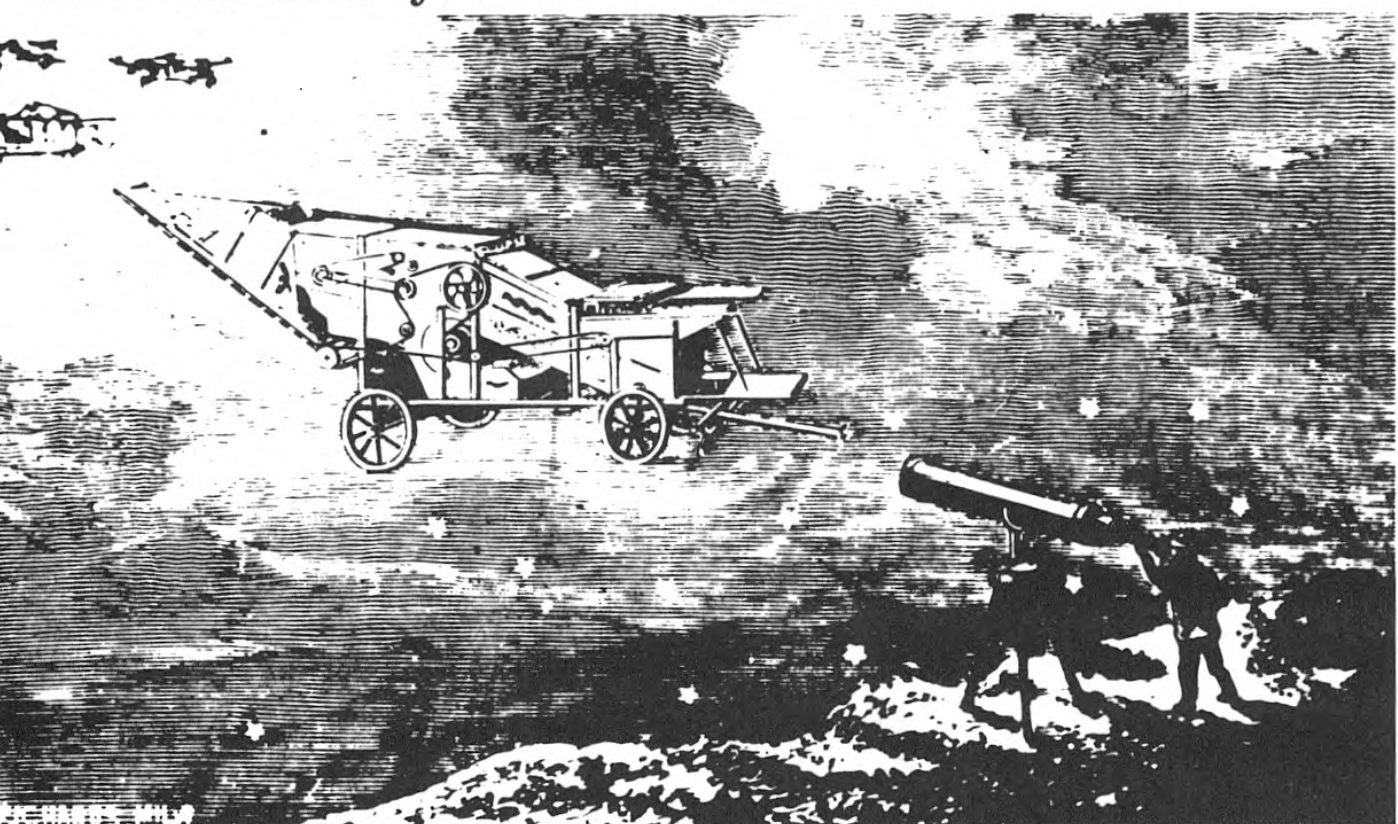

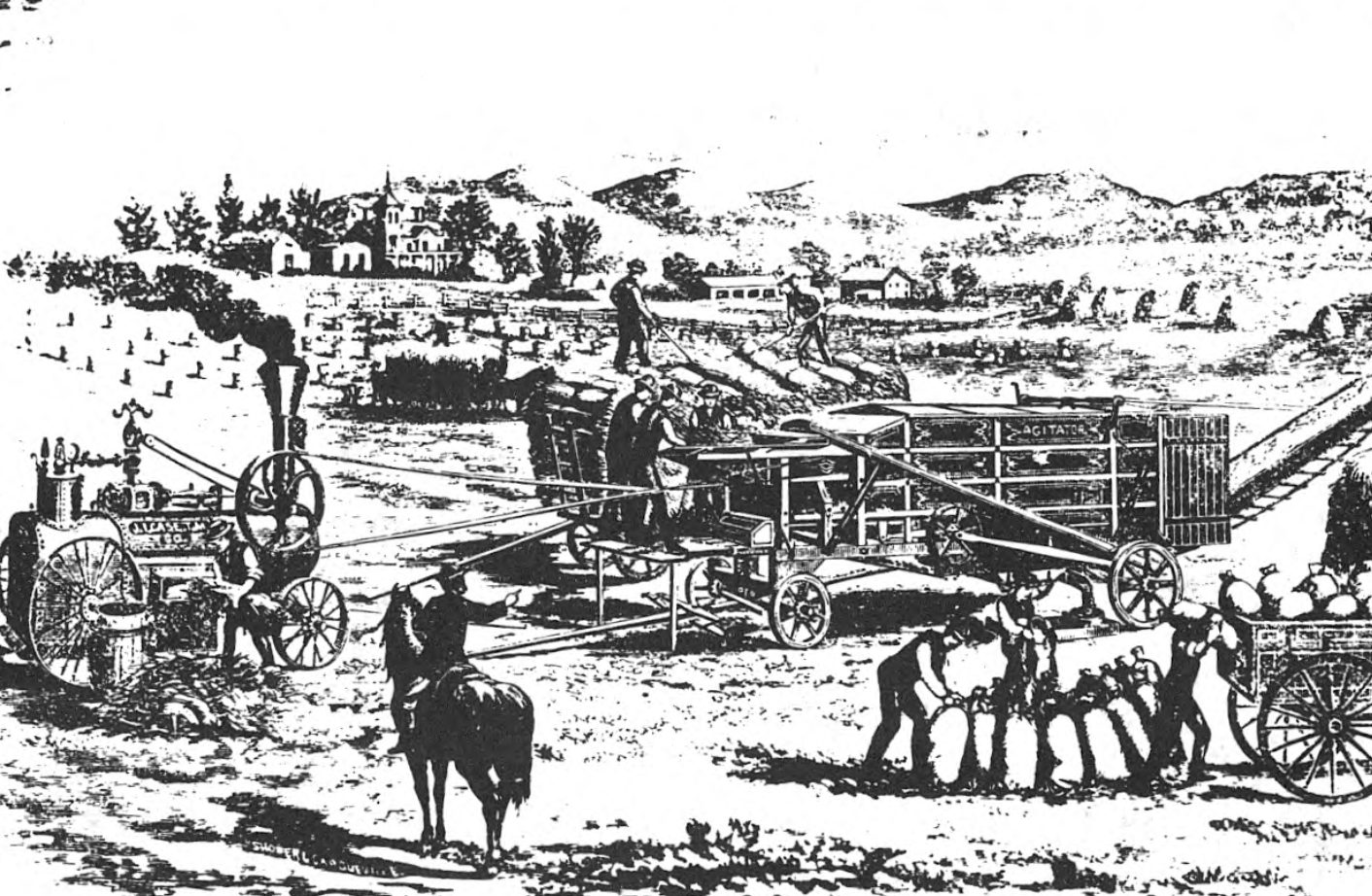

Also announced in 1869 was the Case portable steam engine, ostensibly designed to power the new Eclipse threshers. In the planning stages for several years, the steam engine finally brought a prime mover to the farm. Hot weather made no difference in the steam engine’s performance. Conversely, in the heat of summer, frequent stops were required so that the draft animals on the sweep power or the tread power could rest.

About 1876 Case went a step further the steam engine, offering a self-propelled “ traction engine.’ ’ At this point the engine was steered by a team at the front. Then in 1884 came an entirely new design intended for drawbar loads in addition to belt work. A steering mechanism was also provided and now a single man could move the engine and thresher from one threshing site to another. By the time Case left the steam engine business in 1926 they had built more engines by far than any other competitor.

For several reasons the partnership of J. I. Case & Company ended in 1880. In its place came a new $1 million corporation known as J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company.

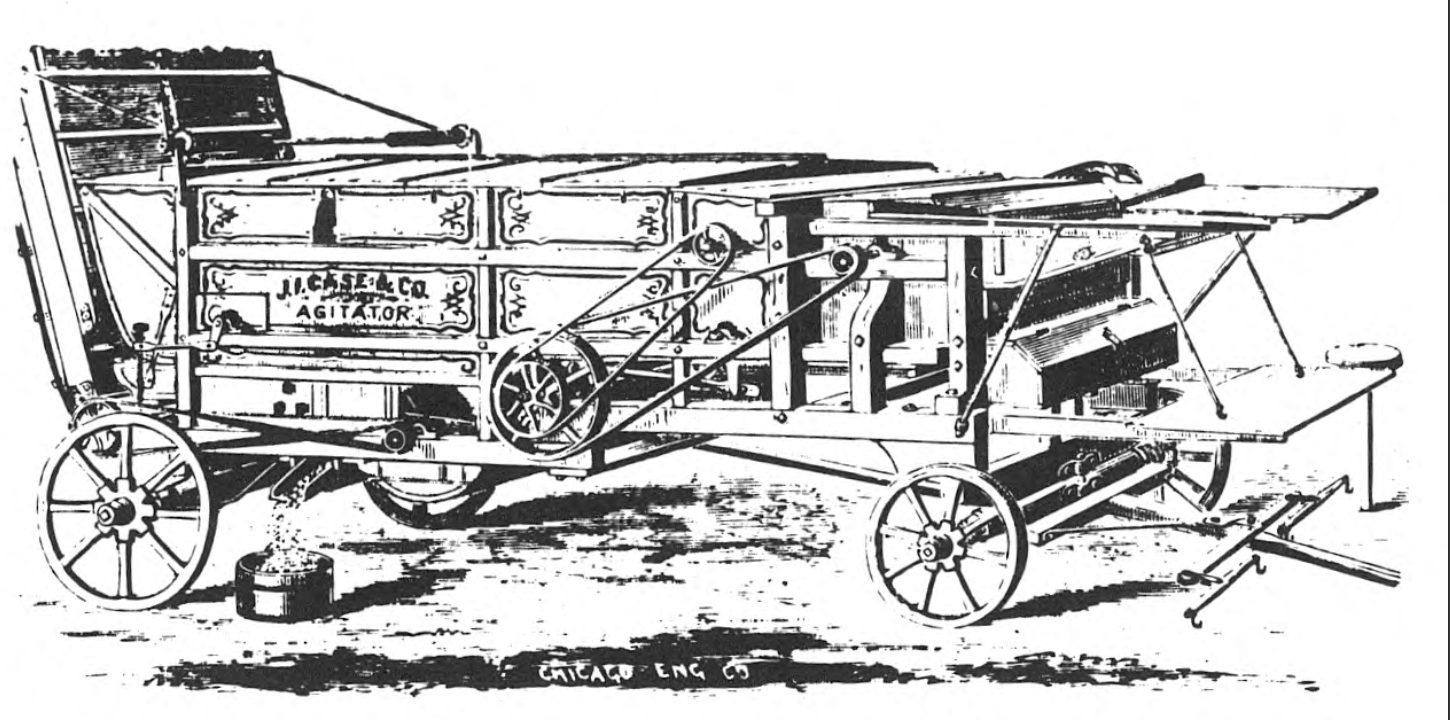

Coinciding with this change, Case announced an entirely new thresher design dubbed the Agitator. The Agitator with its vibrating straw racks marked a distinct change in separating methods for Case. In fact, the general design is used to this day by the majority of grain separating mechanisms, whether on threshers or on combines. Shortly after the Agitator was introduced, cast plates replaced some of the wooden side sections, and thereafter the machine was known as the Ironsides Agitator. Perhaps the term was self-suggestive due to its “ iron sides.” Perhaps there was an implied reference to the robustness of a machine with iron construction, and perhaps the term may even have been suggestive of that famous old frigate, the U.S.S. Constitution, affectionately known as “ Old Ironsides.” However this thresher got its name, the Ironsides Agitator remained the flagship of the Case line until 1904.

The Agitator separator was largely the work of W. W. Dingee. The latter arrived at Racine in 1863, having previously worked at Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia and for the A. B. Farquhar Company at York, Pennsylvania. Dingee and Case became close friends, perhaps because, as Dingee once noted, “ Case and I were both in love with the threshing machine business. . . ” Dingee was also well known for his improvements to the old Woodbury sweep power; the improved machine being sold for years as the Improved Dingee-Woodbury Power.

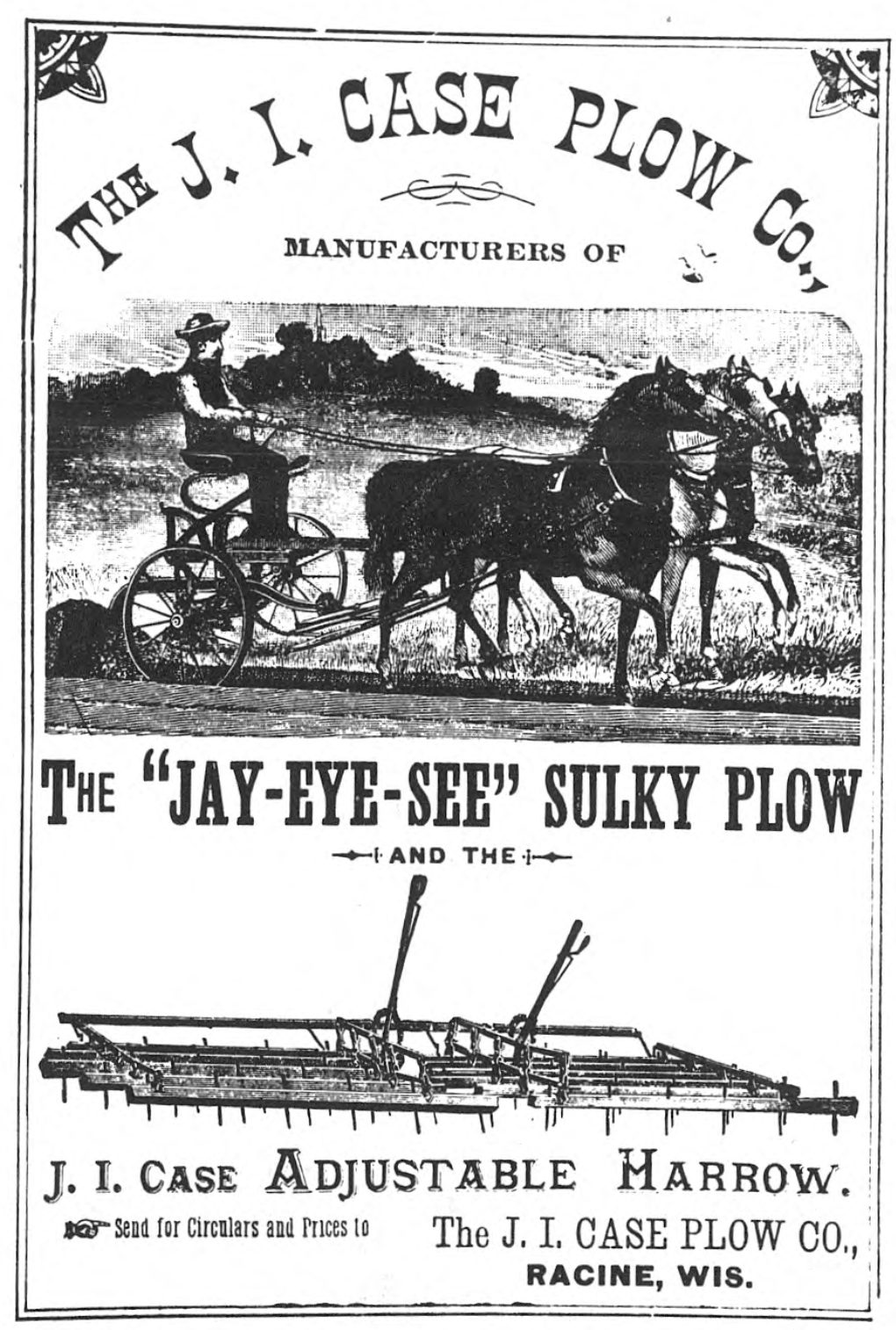

Despite his love of the thresher business, Case organized a new plow factory in 1876. Initially known as Case, Whiting & Company, it came under total control of Case in 1878 through his purchase of the Whiting interest. At this point the firm was known as J. I. Case Plow Company. Another reorganization in 1884 brought the final title of J. I. Case Plow Works.

At this point in time Case seemed to lose his enthusiasm and affection for both the thresher business and the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company. Perhaps nearly a half century of the threshing machine business led him to seek new challenges. Perhaps he saw the plow business as an industry just on the brink of major new developments. Whatever the reasons, they are now clouded by time. It is related that even his own family was never sure of Mr. Case’s thinking in this regard.

Shortly after the reorganized Plow Works came into existence, Case apparently relinquished most of the control of the Threshing Machine Company and concentrated his efforts on the Plow Works.

After his death in December 1891 Mr. Case’s will directed that the family dispose of all his stock in the Threshing Machine Company, and further directed that his heirs should inherit the Plow Works. Thus, Racine was left with two separate and distinct companies bearing the name of J. I. Case, but having no corporate connection with each other.

With the facilities of the two companies located in adjacent buildings, problems between the two remained for years. The most notable legend in this regard has it that representatives of both firms appeared at the Post Office every morning, each being sure they got the proper mail. These problems finally ended when Massey- Harris Company bought out the Plow Works in 1928. Immediately thereafter, the Threshing Machine Company purchased all rights to the Case name from Massey-Harris for $700,000.

Particularly during the last ten years of his life, J. I. Case began investing in ventures outside his factories. One such deal involved the single-handed purchase of 60,000 acres of land in Texas. Case was also a director of several Wisconsin banking houses.

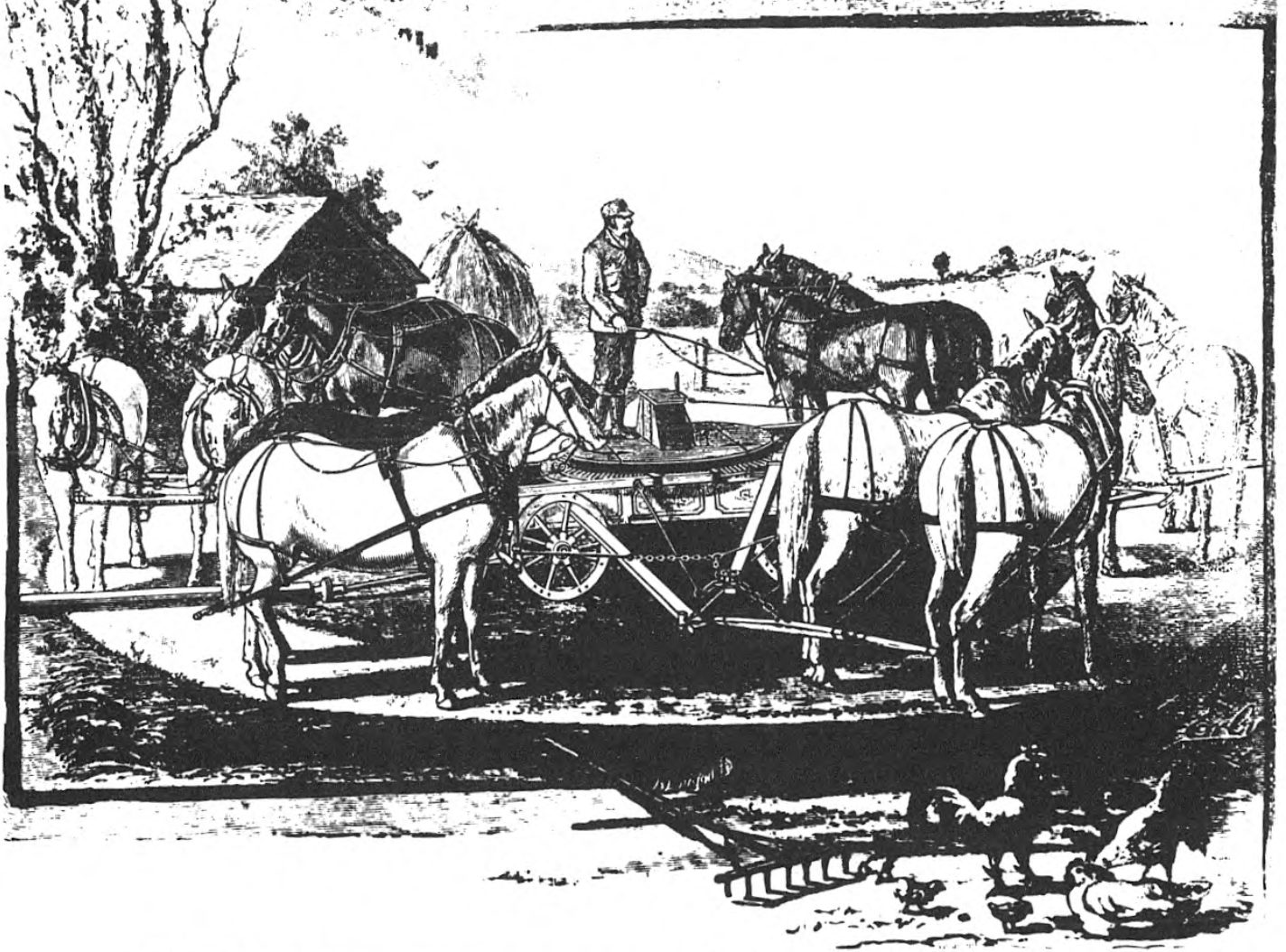

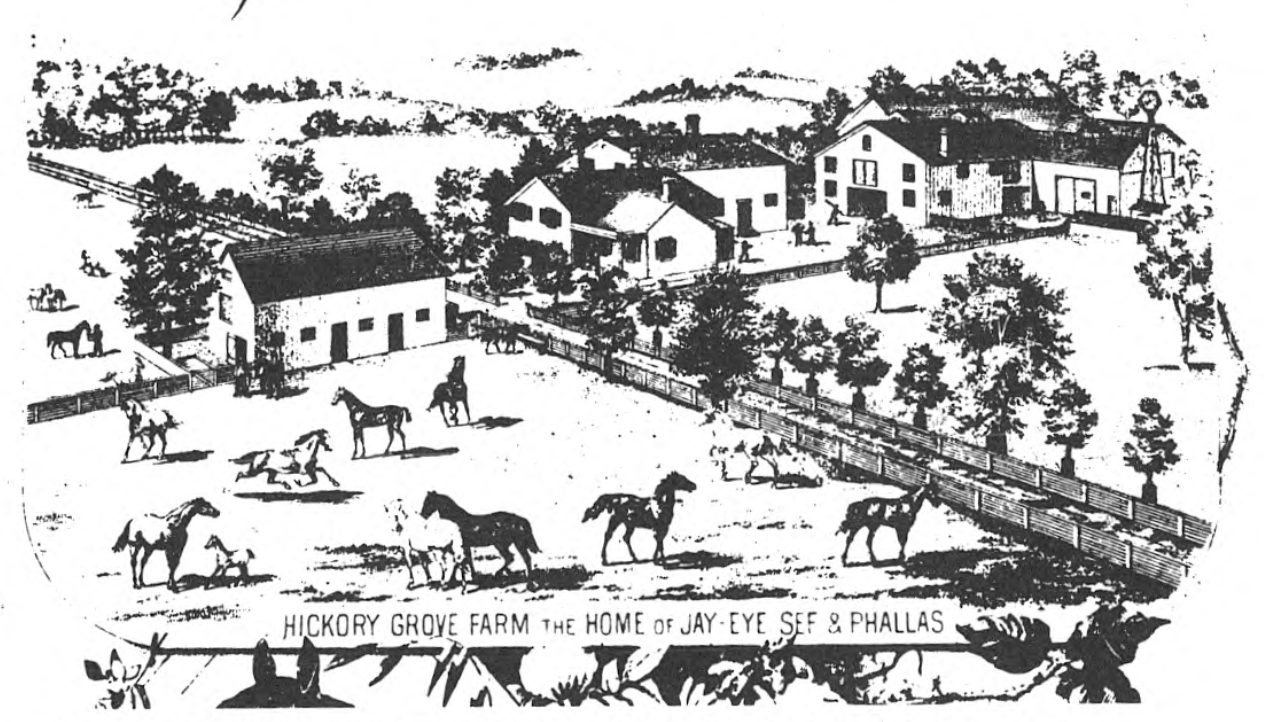

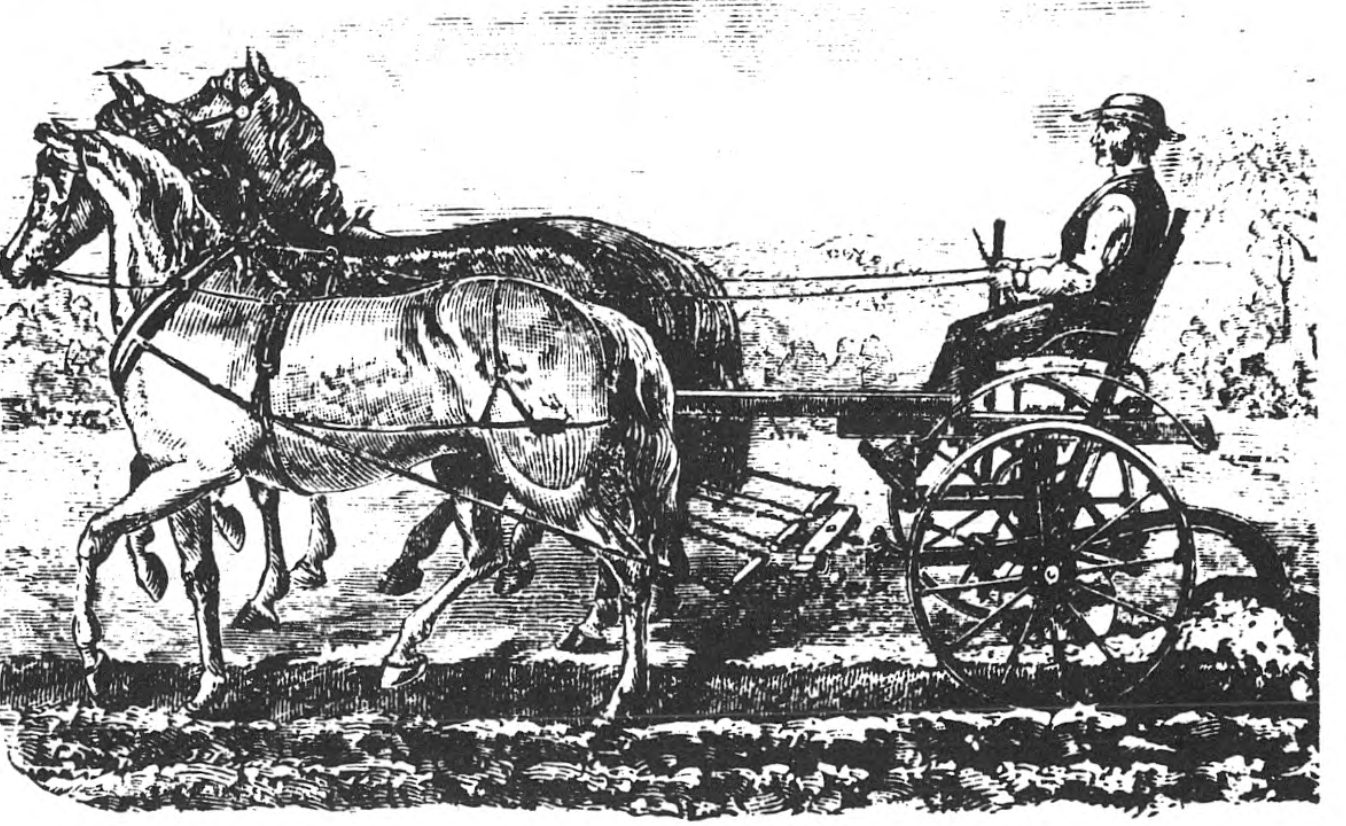

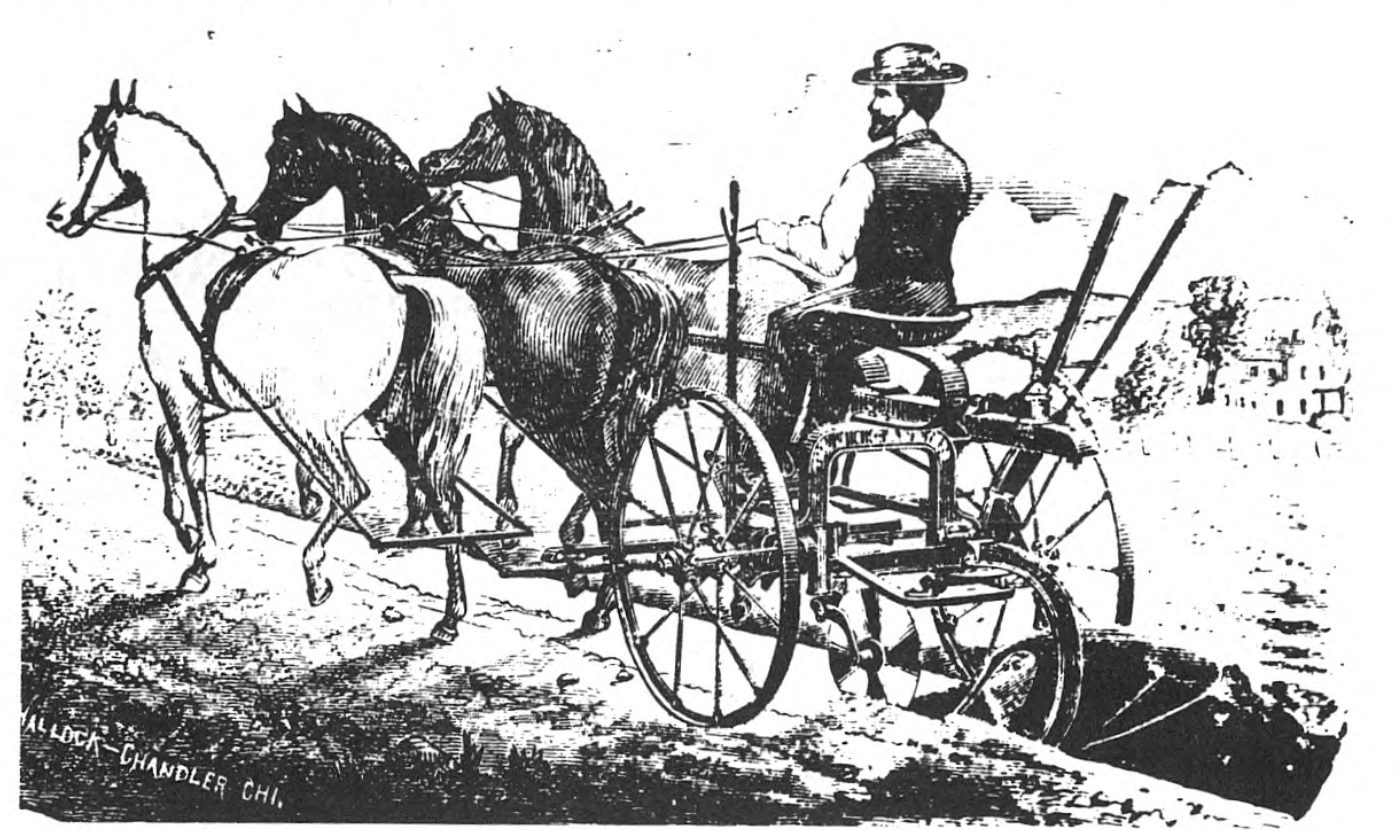

During the 1870s however, came the indulgence of an entirely new hobby—that of fine horses. The first step was the purchase of a 200 acre farm called Hickory Grove, located near Racine. Hickory Grove soon had a 1/8 mile covered track, along with new barns, stables, and other buildings. Then Case went to Louisville, Kentucky and purchased the old-line Glenview stud farm. From there to Rhode Island and the purchase of the stallion Governor Sprague for $27,500.

Estimating the success of the Case stud farm after a century-plus would be a subjective judgment at best. However, in 1889 Case spent $500 for a little black gelding which he appropriately named Jay-Eye-See. Within a year the black gelding began to show promise, and in September 1883 he won a match race against St. Julien, one of the fastest trotters of the day. Within a year Jay-Eye-See stepped the mile at 2:10 flat for a new record. Shortly after this the black gelding ruptured a ligament and was forced into retirement at Hickory Grove.

Eight years after being retired as a trotter he was taught to pace. Then in August, 1892 Jay-Eye-See paced the mile in 2:06 1/4 for a new world’s record, making him the world’s all-time champion double-gaited racer.

J. I. Case never lived to see this final victory. He had passed away a few months earlier. For his part, Jay-Eye- See enjoyed his subsequent retirement at Hickory Grove Farm, living there to the ripe old age of 31 years.

After the death of J. I. Case in 1891, Stephen Bull, an original partner, assumed the presidency of the T.M. Company. The following year the company announced their first gasoline tractor. Despite the greatest efforts of Case engineers the Patterson tractor was a failure. It would be nearly twenty years before Case again entered the tractor market. Meanwhile, the steam engine and thresher business continued to prosper, with Case assuming a role as the world’s largest manufacturer of steam traction engines and grain threshers.

The all-wood construction of threshing machines created continuing problems. Only the very best wood could be used, and it had to be thoroughly dry before it could be dimensioned for use in a machine. A great many threshers never saw a shed, and with a constant assault by the elements, the wood alternately swelled and contracted, often leading to misalignment and premature part failure. Fires caused by static electricity were an occasional problem, particularly when threshing grain which had been infected with smut. This plant disease is caused by a parasitic fungus, and at this point in time it occasionally reached epidemic proportions.

Owing in large part to the work of W. W. Dingee, the T.M. Company announced a revolutionary all-steel thresher in 1904. Initially received with hostility, the all-steel thresher soon became immensely popular. Eventually, almost all the old-line companies opted for the all-steel design.

Obviously intent on broadening the product line, Case bought out the small Pierce Motor Company of Racine in late 1910. From this acquisition the T.M. Company soon began producing automobiles. In 1912 the Case-Sattley plows were announced, followed the next year by the Case-Racine plow line. These were built by the Racine-Sattley Company at Springfield, Illinois. The T.M. Company’s entry into the plow market under the ‘Case’ name raised the ire of the people over at J. I. Case Plow Works right across the aisle. This disagreement culminated in a suit filed by the Plow Works against the T.M. Company, and was finally settled in December 1915 by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Further details of this suit will be found under the J. I. Case Plow Works heading within this volume.

Beyond its already established lines, Case sought to expand even further, introducing a line of road and construction machinery in 1912. Steam rollers, road graders, rock crushers, and other machines were included.

A further broadening of the Case line came with the 1919 purchase of Grand Detour Plow Company at Dixon, Illinois. Now, despite a court ruling stating in effect that the T.M. Company could not sell plows under the ‘Case’ name, the T.M. Company could and did market its own line of Grand Detour plows and tillage implements.

In 1928 the T.M. Company regained all rights to the ‘Case’ name, but to the tune of $700,000. After buying the J. I. Case Plow Works, the Massey-Harris Company immediately sold the ‘Case’ name back to the T.M. Company. Concurrently, Case dropped ‘Threshing Machine’ from the corporate name and became known as J. I. Case Company. As will be noted under the J. I. Case Plow Works heading, the T.M. Company was effectively nullified in an earlier effort to adopt this tradename by the Plow Works people.

Another noteworthy acquisition was the 1928 purchase of Emerson-Brantingham Company at Rockford, Illinois. Their extensive line of harvesting, haying, and tillage equipment brought Case into the realm of a full-line company.

On the tractor scene, Case piloted their big 30-60 model in 1911, going into production for the 1912 season. Also coming out that year was the 20-40 model; it was to become the standard-bearer for several years to come. There are indications that from 1912 to 1914 the engines for Case tractors were built by Davis Motor Works at Milwaukee. In fact, it appears that the 20-40 engine was designed by Davis—he also had designed the engine used in the Avery tractor built at Peoria, Illinois. Perhaps this accounts for certain similarities of design between the two engines.

In 1915 Case joined the then-current craze for a small three-wheeled tractor. Their response was a 10-20 model, ostensibly built as a competitor to the Bull tractor coming out of Minneapolis. Between the unit frame design of the Wallis, the small size and maneuverability of the Bull, and Henry Ford’s cast iron fury dubbed the Fordson, the old-line engine and thresher builders raised myopic eyelids to discover that they were about to drown in a sea of heavyweight tractors. It was obvious that they could no longer build what they thought the farmer needed—now they would have to furnish what the farmer wanted—and in this case it was a small lightweight tractor.

Some of the old-line builders persisted in the old ways, and eventually went out of business, quietly and unnoticed. For their part, Case was quick to respond to the new challenge, introducing the 10-20 three-wheeler in 1915. The following year came the 9-18, a small compact design featuring a four-cylinder crossmounted engine. Until the 1929 introduction of the Model L, crossmounted engines were featured in all Case tractors. On the heels of the Model L came the CC row-crop model and an extensive line of tractor-mounted implements.

The 1936-40 period saw the introduction of the RSeries tractors, while the popular D-Series made its debut in 1939. The following year, 1940, witnessed the new S and V-Series tractor models. From this point on, the Case tractor line kept pace with a fast-changing industry. Perhaps, in what could be called the irony of ironies, the Case acquisition of International Harvester in November 1984 brought matters full circle. Could it be supposed that J. I. Case the thresher builder and Cyrus Hall McCormick the reaper builder, could ever have imagined their two great companies being welded into a consolidation with a worldwide market? Since the term, ‘rugged individualist’ was epitomized in Jerome Increase Case and Cyrus Hall McCormick with equal measure, it seems unlikely that any such thoughts were ever entertained, even in their most frenzied imaginings!

Since this volume is intended to illustrate the career of the Case companies as seen through their products, this biographical sketch of Jerome I. Case is probably too brief for some, and too detailed for others. Various aspects of J. I. Case and his contemporaries will be found within the many product categories of this book.

J.I. Case

J.I. Case Plow Works

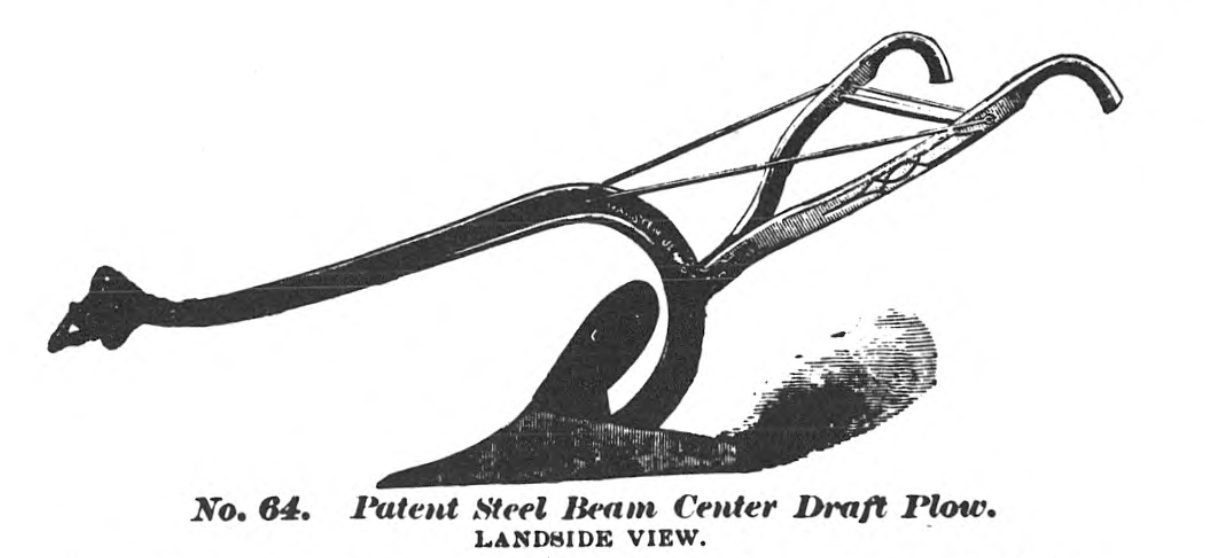

During the early 1870s Ebenezer G. Whiting developed a new ‘center-draft’ plow. J. I. Case provided the financing for this venture. The manufacturing facilities were arranged for by David Bull, a relative of J. I. Case. During 1876 the firm of Case, Whiting & Company was formed. The name was changed to J. I. Case Plow Company in 1878, reflecting Case’s buyout of Whiting at that time. Then in 1884 a reorganization was effected and the firm was, from that day forward, known as the J. I. Case Plow Works.

Numerous writers have indicated that the Plow Works, almost from its very beginning, shared but a fraction of the success enjoyed by the T. M. Co. (Threshing Machine Company). In most of its aspects, the career of this firm was not a particularly joyous one.

During 1890 J. I. Case withdrew from the management of the Plow Works, naming his son, Jackson I. Case to the presidency. The latter seems to have had only a shadow of the fascination for the plow business that was manifested by his father. Thus, Henry M. Wallis assumed the presidency of the Plow Works in 1892.

H. M. Wallis was born at White Pigeon, Michigan in 1861, coming to Racine as a youngster. In 1877 he went to work for the Mitchell-Lewis Wagon Company in Racine. At age 20, Henry married Jessie Fremont Case, one of J. I ’s three daughters. Their two children were Lydia E. and Henry M. Wallis Jr. During 1883 J. I. Case put his son-in-law in charge of the Fish Bros. Wagon Company. This firm had come into hard times and J. I. Case, its chief financial backer, had assumed control.

The Fish Bros. Wagon Company connection to J. I. Case is most difficult to unravel. Most of the available information is buried within the Northwestern Law Reporter and is cited as 15 N.W. 808ff. This litigation was initiated by J. I. Case against the Fish brothers and others for recovery of principal and interest on loans dating to 1868, and perhaps earlier. Initially at least, the agreement was a verbal one, whereby J. I. Case became the absolute owner of the Fish Bros, plant and inventory, and the brothers in turn were to manage the firm as agents for J. I. Case. This plan was to remain in effect until the obligations were paid. Apparently after the debts were satisfied, the facilities and inventory would then revert back to Fish Bros.

The Case v. Fish case was filed with the Wisconsin Supreme Court May 31, 1883. To sum everything up in a few words, Case wanted the money, while Fish Bros, counterclaimed that the interest rate of 10% on some notes, and apparently as much as 12.2% on others, constituted usury. In a lengthy opinion, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to circuit court for further action. The details of the final settlement have not been located during this research, but obviously, J. I. Case ended up with the Fish Bros. Wagon Company and placed his son-in-law in charge of this factory. From all appearances, Wallis soon moved over to the Plow Works as General Manager, finally assuming the presidency in 1892, only a few months after the death of J. I. Case.

Current research has failed to creditably trace the activities of H. M. Wallis during the next few years, although it is obvious that he was at the helm of the Plow Works throughout this period. Even the synoptic history of the company as presented in Poor’s & Moody’s Industrials fails to provide any substantive data on company activities and developments for the two decades following 1892.

The Wallis Bear appeared in 1912. This huge tractor had little appeal, and very few were sold. An undetermined connection appears to have existed between this design and another large tractor built by Ajax Auto Traction Company at Portland, Oregon. Wallis Tractor Company was initially located at Cleveland, Ohio. Although the Bear made no major impact on the market, Wallis persisted in an attempt to build a successful tractor. By 1912 the Walhs Tractor Company had offices in Racine, along with the factory in Cleveland. Shortly thereafter, the manufacturing facilities appear to have been moved to Racine, apparently occupying a portion of the space within the Plow Works buildings. Wallis Tractor Company and J. I. Case Plow Works remained as separate business entities until they were consolidated as J. I. Case Plow Works Company. This consolidation and incorporation was initiated on July 28, 1919 and registered in Delaware.

The friction between the T.M. Co. and the Plow Works people finally led to a celebrated case before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. (See 155 N.W. 128; Northwestern Law Reporter.) It provided some good reading for the farm press during 1915 and 1916. Filed by the J. I. Case Plow Works on December 7,1915 this action alleged unfair competition in trade against the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company. The suit sought to restrain the T. M. Co. from using the words ‘Case’ or ‘J. I. Case’ either alone or in combination with other words upon plows or plow machinery sold by it, as well as in advertising of such plows and plow machinery.

A considerable amount of company history is embedded within this action. Revealed is the fact that in 1876, Case, Whiting & Company was organized. Immediately, this firm began building common walking plows, sulky plows, harrows, cultivators, and other tillage implements. When the company failed in 1884 the property and good will was sold to J. I. Case who then organized the J. I. Case Plow Works and conveyed to it the property of the former company. Also of note is a statement to the effect that in 1890 Mr. Case transferred practically all the stock in the Plow Works to his daughter and her husband, H. M. Wallis. Meanwhile, Mr. Case remained as President of both the Plow Works and the T. M. Company up to his death in 1891. For some years following, these two entirely separate Case factories operated with reasonable harmony. Cooperation was not difficult, since the T.M. Company made threshing machines and steam engines, while the Plow Works busied itself with tillage implements.

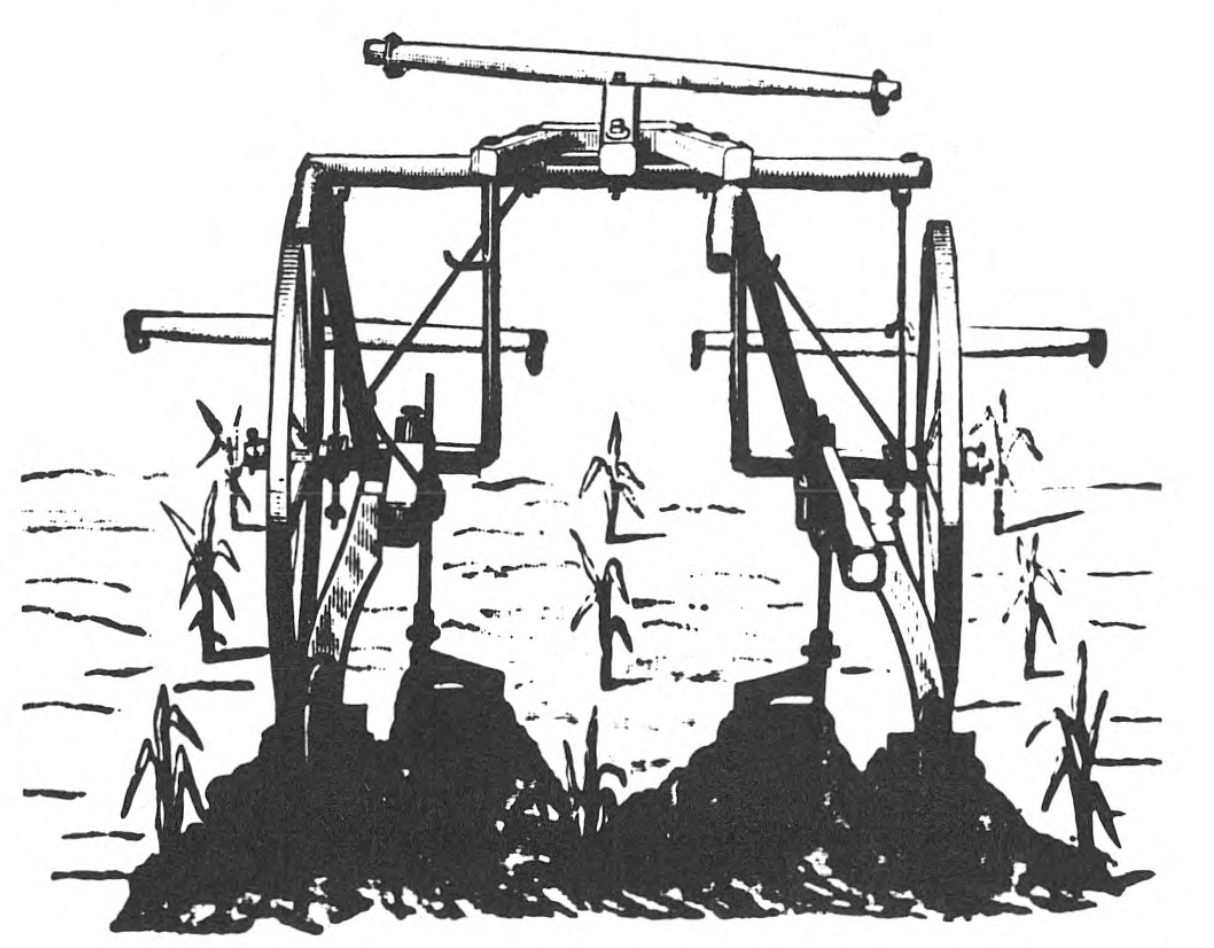

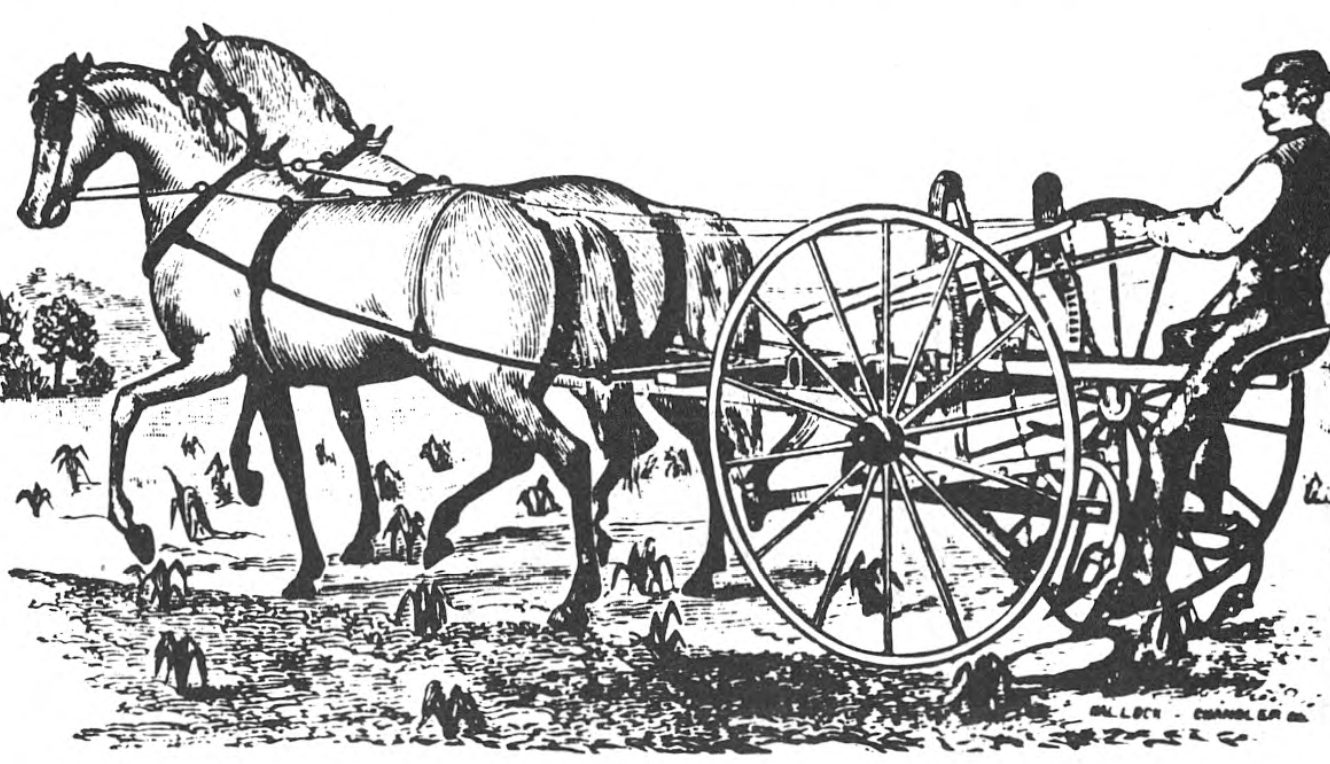

During 1893 the Plow Works modified some horse drawn plows for use behind steam traction engines. These were sold to some extent for a decade beginning in 1893. After 1903 the Plow Works attempted building an engine plow but these experiments met with little success until 1909. Meanwhile, they continued attaching beams and moldboards from horse plows to a heavy frame designed for the steam traction engine.

The T. M. Company involvement in plows began almost by accident. During 1889 Jacob Price of California contracted with the T. M. Company to manufacture for him a large traction engine designed especially for plowing purposes. Between 1889 and 1893 these experiments continued, and by the latter date, Price owed the T. M. Company some $11,000. At this point, Price transferred all rights to the engine, plow, foundry patterns and other items to the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company. Subsequently the T. M. Company built and sold a few of these engines, using plows bought from the Plow Works. In fact, the T. M. Company advertised this design for a couple of years as the “Jacob Price Steam Plowing Outfit.” During 1894 the T.M. Company issued a catalog devoted to the “ ‘Jacob Price Field Locomotive,’ Mfd. at the Works of J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company, Racine, for Jacob Price.” A year earlier the Plow Works advertised this very same outfit as the ‘Jacob Price Field Locomotive & Steam Plow.’ However, both firms ceased production of the Price design by 1897.

After the demise of the Price steam plow, the T.M. Company was left with a sizable inventory of parts from this venture. Thus in 1900, the T.M. Company began building an engine plow made up entirely from parts conveyed to them by Price in 1893. This was apparently the first instance in which the T.M. Company used the word ‘Case’ on a plow. Few were sold, but at least one unit was placed with a farmer near Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1902. During the same year the T.M. Company began building a triangular, wheeled platform which was attached to the engine drawbar. On the rear of the platform the plows were attached. Thus, this platform became the connecting link between the engine and the plows. Records show that between 1902 to 1912 the T.M. Company sold some 373 of these attachments, still it made no plows.

During 1909 the T.M. Company built and experimented with an engine gang plow with individual beams, but sold none, and abandoned the experiment. Nothing further was done by the T.M. Company until early 1910, when it built what it termed as a ‘steam-lift engine gang plow.’ It embodied a new design, and during 1910 and 1911 the company built 63 of these outfits, of which 27 were returned as being unsatisfactory. The advertising of this new plowing outfit as a ‘Case’ plow began in trade journals during January 1911. Up to that time the T.M. Company had never advertised any plows in the trade journals (except for the Jacob Price outfit). Additionally, the T.M. Company had never made any plows prior to 1911, and in fact, their advertising of as late as 1909 indicated that they did not manufacture or furnish plows.

During 1912 the T.M. Company contracted with the Racine- Sattley Company of Springfield, Illinois for a large number of engine gang plow bottoms. They were marked as ‘Case-Sattley engine gang plows’ and sold by the T.M. Company during that season from Racine. The following year another contract was made, but these plows were marked as ‘Case-Racine’ and a substantial number were sold in connection with the Case steam traction engines.

Through this period the T. M. Company was also involved in the introduction of a light farm tractor. Thus it was in 1914 that production began on a lightweight engine gang plow for use with light tractors. These plows had the word “ Case” stencilled in large letters on the plow beams. This plow, as produced by the T. M. Company, was quite similar to a plow introduced by the Plow Works people during the same year, 1914. Compounding the conflict, the T. M. Company had begun marketing a road grading and breaking plow in 1910. It too had the word ‘Case’ on the beam in large letters. Meanwhile, the Plow Works had been marketing a similar plow for several years, it too, carrying the Case tradename.

The J. I. Case Plow Works took notice of the use of the word ‘Case’ on plows emerging from the T. M. Company shops early in 1912. Immediate verbal and written protests followed. Apparently, reasonable harmony between the two firms existed so long as the name was used on non-competing lines. From March 1912 on, virtually every pretense of harmony evaporated. In fact, the downhill slide began in earnest several months earlier. The T. M. Company had decided to change its corporate name simply to ‘J. I. Case Company.’ Word of the impending change leaked out, and so H. M. Wallis, H. M. Wallis Jr., and Jerome I. Case II immediately formed a corporation under that name during January 1912. This stopped the T. M. Company dead in its tracks so far as their plans were concerned. Fueling the fire still further, the new J. I. Case Company, headed by the same people in control of the Plow Works, then demanded that the Post Office forward to them any mail so addressed. Since much of the rural correspondence was thus addressed, the T. M. Company immediately protested to the Post Office. A directive followed in May of 1912 giving any mail with an ambiguous name and with no specific street address to the T. M. Company.

After the smoke cleared, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that the Plow Works was entitled to the use of the word ‘Case’ on its plows. Furthermore, the T. M. Company was enjoined from using the term on their plows, but was free to use the word ‘Case’ on their other machinery, as in the past. The court ruling also provided specific rules regarding the receipt of mail, going so far as to permit submission of disputed mail to the court for its determination. When the Plow Works was sold to Massey-Harris Company in 1928, the T. M. Company purchased all rights to the ‘Case’ name, finally acquiring the right to use this term in connection with their plows.

During these years of controversy and animosity between the two companies, the Plow Works was nevertheless continuing their work on farm tractor development. Little information can be found on the Wallis Bear, or on the Wallis Fuel-Save models. The latter was apparently introduced about 1912, and was rated at 40 drawbar and 60 belt horsepower.

Tractor history was made with the 1913 introduction of the Wallis Cub. This was America’s first unit frame design, despite claims of Henry Ford and others to the contrary. The major difference between the two designs was that the Wallis used steel boilerplate for the frame, while Henry’s little Fordson a few years later used a cast iron frame.

Clarence M. Eason and Robert O. Hendrickson designed the Wallis Cub, receiving patent protection under No. 1,205,982. Although the Cub used open final drives, the Wallis Model J, also known as the Cub Junior, made additional history by featuring fully enclosed final drive gears. With a Wallis-built engine, the Model J featured two forward speeds, along with Hyatt roller bearings throughout the tractor. This alone was a mighty step forward in tractor design, since it marked the end of friction- producing and power-robbing plain babbitt bearings.

The Wallis three-wheel design was a characteristic feature of the Cub and Cub Junior models. With the 1919 introduction of the Model K tractor came a standard four-wheel design which continued the boilerplate frame that by now had achieved fame for itself. During 1922 the Model OK tractor appeared; it was an improved and slightly more powerful version of the earlier Model K tractor. Like many other equipment manufacturers of the period, the Plow Works also experimented with a motor cultivator, offering one such outfit in 1919. This particular machine featured individual rear wheel brakes, a genuine peculiarity for a tractor of 1919!